When thousands of lower-waged University of Georgia employees went into the holiday season with only half a paycheck last winter, Joseph Fu decided enough was enough.

“Staff and even faculty are extremely weak in this establishment,” the UGA math professor said. “It seems like faculty… are treated with almost open contempt.”

Fu is now leading a newly formed United Campus Workers union at the university, in hopes of giving a voice to underrepresented staff members.

The widely criticized transition in pay schedules last fall was the spark behind the idea, Fu said. A proposed change to the Fair Labor Standards Act last year raised the threshold for overtime compensation to $47,476 a year, meaning anyone who made less than that was eligible for overtime pay. Under state law, anyone eligible for overtime pay must be paid on a biweekly basis, so over 3,000 employees at UGA are now paid every other week rather than once a month. (Courts and the Trump Administration have put the FLSA rule on hold, but the new pay schedule remains in effect.)

“The easiest thing to do would be to put all these workers on a bimonthly salary. The claim is, though, that the University System of Georgia does not have a bimonthly salary classification. Everyone paid more than once a month has to be an hourly worker,” Fu said. In addition, University of Georgia officials said they required eight days of lag between the end of a pay period and payday for hourly workers. “The net effect was, many people—many of whom I know are good people and hard workers—went into the holiday season half a month short of pay,” he said. “This was a year ago. It was outrageous.”

It wasn’t just the deferred paychecks; the way the administration handled the situation also infuriated Fu. “UGA Human Resources ran these information sessions, and some of the explanations they offered were just insulting. Someone asked, ‘So, we’re not getting paid for eight days, so where’s the money?’ ‘Well, there is no money,'” he said. Eventually, Human Resources explained that $1,000 was sitting as a placeholder to act as a rolling balance.

Administrators suggested that those concerned about the gap in pay could take out a loan. That, of course, would accumulate interest and have to be paid back. “It was a flat-out insulting answer. That response was disrespectful, borderline contemptuous,” he said. “When I heard it, I was furious that an organization to which I give a lot would treat my colleagues in this manner.”

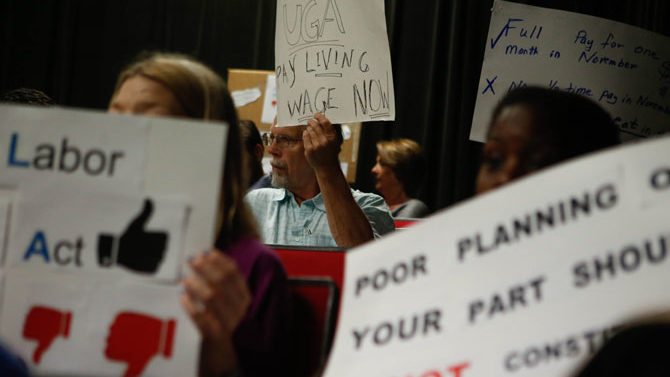

Fu.

Despite being a full-time professor and therefore not affected by the FLSA change, Fu decided to get involved. “I got to know clerical staff, and so I was worried about this FLSA mess, and after these insulting responses, I felt I couldn’t sit still, I couldn’t stay quiet.”

Fu participated in demonstrations with the Economic Justice Coalition at the Arch last fall. There, he met an organizer from the Communications Workers of America and considered the idea of forming a union.

A meeting of three people in his office in October quickly grew to a dozen. As of the middle of November, the union had more than 60 members and has applied for a charter from the CWA. Even more people expressed interest in joining after a recruitment blitz before Thanksgiving break.

One of the first organizers with Fu, a longtime UGA employee who wished to stay anonymous due to concerns over job security, said she feels outlets such as university council and staff council are ineffective, and that staff are “being sidelined and marginalized, especially after the FLSA debacle.”

The FLSA transition was what motivated her to get involved, after she personally lost $1,800 in deferred wages around the beginning of December 2016.

Union organizers sent out a survey to see how other people were affected by the pay transition. “Some people were having to pull their children from daycare. They weren’t able to have a regular Christmas, they had to really watch their food,” the employee said. “All sorts of things that they shouldn’t have had to do, especially in the last month before the holiday.”

Both Fu and the other employee have questions about the rolling balance, now that the FLSA overtime rule change is no longer in effect. “Where is our money now? For people who were taken off salary and put on a biweekly pay, we can only receive that money back if we move into a salary position again, or if we retire or leave the university,” the employee said.

With the FLSA shot down, she wonders why people aren’t being transitioned back to salary positions. “Why have those people that had eight days of pay taken away from them—why isn’t that money being returned to them?” she asked.

The FLSA change, however, is not the only recent example of faculty and staff being undermined, Fu said. The debate last spring over UGA’s academic calendar—many professors were concerned that UGA’s calendar was longer than that of other University System of Georgia institutions such as Georgia Tech and Georgia State—is another situation where faculty input was glossed over. “The administration deferred to the Board of Regents, which decided recently that UGA’s calendar was the proper length and that other institutions’ calendars were actually too short,” he said.

With the new ruling, some faculty members tried to help reform the calendar, Fu said, but the USG decided earlier this month that academic calendars would not be set by faculty members, but by college presidents. According to the Athens Banner-Herald, UGA President Jere Morehead has assigned Rahul Shrivastav, the vice president for instruction, to create the calendar, taking into consideration faculty advice.

“In my mind, there’s a number of related issues: the treatment of our colleagues who may work clerical jobs and are underpaid, and the passing of the buck of the UGA administration up to the Board of Regents,” Fu said.

Initially, though, the union plans to focus on fair compensation for lower-paid staff and for part-time instructors and adjunct professors. “We also want to stop the streamlined process of hiring temporary workers,” the anonymous employee said. “They’ve been here for 10 years, but they still don’t have benefits. They get minimum wage. They’re not getting any retirement of any sort. It’s just perpetual.”

The union will likely face an uphill battle. State employees are barred from striking or collectively bargaining, and Georgia is a right-to-work state, meaning the union cannot hold an election and compel everyone to join if it wins a majority. “We can’t strike, nor do I want to,” the employee said. “I feel so strongly that the best part of my job is working for the student.”

While Fu said they hope to have a dialogue with university administrators, the union is planning to use publicity to push its message. “We do have the power of publicity. We have the power of shame,” he said. “[Administrators] come back and say it’s the USG’s rules and it’s out of their hands. But the reality is these are political issues, and if these people were really motivated to go up and bat for us, they would go up and bat for us.”

So far, UGA officials have yet to comment publicly on the union. The organization is not university-sanctioned, said Gregory Trevor, the executive director of UGA media and communications, who otherwise declined to comment.

“Our plan is to light a fire underneath them,” Fu said, referring to the administration. “We know they experience pressure from above; let’s see if we can generate some pressure from below.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.