Saturday in Knoxville got off to a dreary start. As mentioned, we missed Laraaji’s laughter meditation trying to get our batteries charged up. I headed straight to an interview with Jeff Cuellar, the Director of Connectivity for AC Entertainment. AC runs and created the Bonnaroo, Big Ears, Mountain Oasis and Forecastle music festivals. They also produce concerts and collaborate on productions across the country. Jeff is a well-spoken, dedicated, long-term member of the AC organization. Visually, he could easily be mistaken for “Dawson’s Creek” star Kerr Smith. We walked down Gay Street in the rain to AC’s office atop a downtown bank building, where Cueller broke down some of his company’s history and goals.

Ashley Capps (AC) went to college in Knoxville in the ’70s, where he became involved in promoting and booking shows. In ’88, he opened a jazz club called Ella Guru’s, which lasted about two years. After throwing in the towel there, he was approached about booking a show for Branford Marsalis and got caught up in the fervor. In 1991 he started AC Entertainment with booking contracts around the Southeast including the Tennessee and Bijou Theatres (which AC still books). Inspired by Glastonbury, Leeds and other outdoor European events, he held the first Mountain Oasis festival in 2000 and sold all 6,000 of the available tickets. From there, he set to work on Bonnaroo, eventually coming to own the land that it takes place on—and enjoying massive success.

Big Ears began a few events down the road in 2009, featuring performances by Philip Glass, Pauline Oliveros, Fennesz, Antony and the Johnsons, Negativland and Matmos, to name a few. The event pressed further in 2010, expanding its scope and doubling its roster in collaboration with Bryce Dessner of indie band The National. In its second incarnation, Big Ears adopted its current artist-in-residence format and featured the great Terry Riley. Collaborators and peers included William Basinski, The Books, Dirty Projectors, Gang Gang Dance, DJ/Rupture, Joanna Newsom, Sufjan Stevens and a host of more buzz-leaning projects. Whether it was the muddy programming of the second outing, lack of monetary support or scheduling with Steve Reich, Big Ears went on hiatus for three years.

AC employs around 50 people in Knoxville (including theatre staff), and tries to work with local businesses in production. The festival doesn’t yet have year-round projects in town, aside from booking shows, but it does give to The Joy of Music School and the Community School of the Arts, two organizations affecting local youth music education and involvement with the arts. While the attendance is vastly comprised of out-of-towners, Cuellar claims that local response during the interim was partially responsible for the revival of the event. He was reticent to go into much detail regarding the “dirty secret” and “fine line” of sponsorship, but did indicate it’s something they contemplate.

Our conversation concluded in an uplifting tone regarding 2015, citing how many of the festival’s current structures have evolved from “artist-driven” ideas and highlighting the festival’s willingness to adapt to future proposals. Later that day, I heard Laraaji say, “Improvisation is a wonderful way of canceling the future and the past and just being present.” Fortunately, AC Entertainment seems to agree.

I nearly got lost on my way out of the high-rise and ran into some freaks from Macon (really) down below. We made the misguided decision to eat at a place called Preservation Pub. If you have anything to do with the rest of your day, or like the way food tastes, don’t go here. Several hours later, and without seeing any of Helen Money (or three other acts), we caught some of Wilco drummer Glenn Kotche’s set at The Square Room. This is the least accommodating venue in Knoxville; it was tough to get inside and it was awash with folding chairs awkwardly dispersed in the standing room.

Kotche was set up behind a massive array of percussive accoutrement and projecting an animated video above his kit. Most interesting was a piece of equipment resembling a Guess Who game board with a microphone pointed at it. The box was either home to an extended family of crickets or was otherwise channeling their sounds as he flipped the small pieces on their hinges. His playing was solid enough, and the set may have taken an interesting turn down the road, but it failed to really set my day off.

My compatriot and I set out for the Bijou to catch media darling Oneohtrix Point Never. Daniel Lopatin was set up down-stage left behind a table of equipment and his laptop. Across from him, nearly offstage, was visual artist Nate Boyce, who turned out to be the star of the show. The Bijou sound system provided ample enhancement of Lopatin’s high-fidelity, post-modern, illusory collages. I appreciate the work, and find it sonically thrilling at times, but don’t feel that he presents much beyond aesthetics. Thankfully, Boyce filled in the gaps and then some with his impeccable graphic art. Impossibly rendered, useless, fictional structures and machines evolved and devolved on the screen above. Metals in their liquid and solid forms separated and rejoined in sheer layers of matter. Shapes penetrated malleable planes of varying physical properties and emerged on the other side. Familiar objects and linear environments tickled your conscious mind as your unconscious lay awash in the possibility and the futility of “sense.” The work was astounding, and while I feel it upstaged Oneohtrix, I also think it validated and illuminated his textural approach to crafting rooms of sound in environments that haven’t yet existed. It was an excellent collaboration.

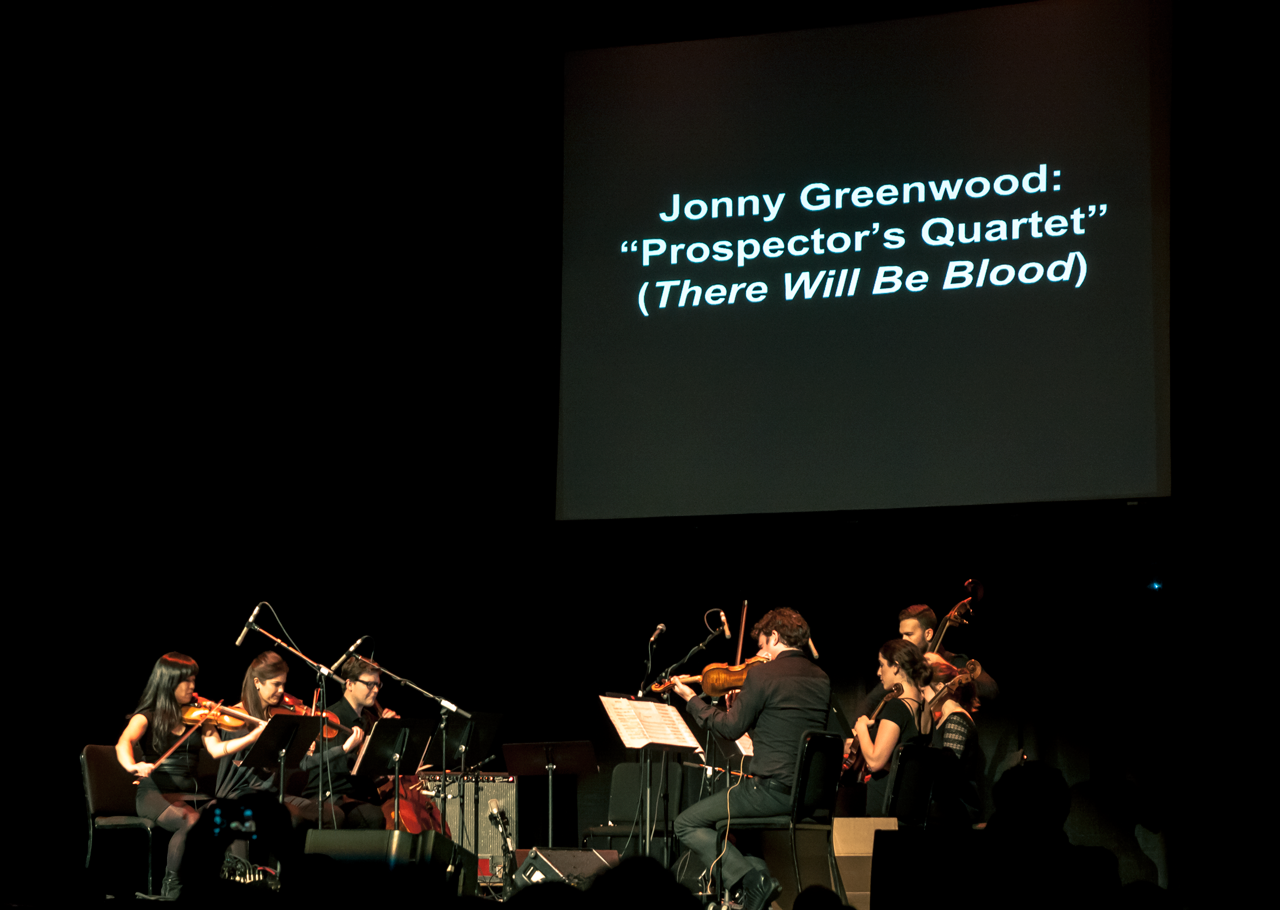

Down the street again, at the Tennessee, a chamber orchestra called Wordless Music performed a stirring set of pieces by Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood, Italian composer and surrealist poet Giacinto Celsi and Greek composer/architect-engineer Iannis Xenakis. The work was performed with grace and great detail. Strings ground against eachother in wavering, unearthly movements. Players spun disorienting aural illusions from simple pairs of ancient acoustic instruments. The experience felt rare and timeless in its setting. To top it off, Greenwood himself collaborated on several pieces, at one point employing the audience and their smartphones as players.

Returning to the Bijou once more, we were treated to a second performance by Zither improviser Laraaji. On this outing, his environment was more accommodating to his presence. With the addition of silent focus and a larger PA, Laraaji took us on a relaxing astral journey alongside “Cosmic Joe and Holy Moe.” Zither, chimes and harmonica reverberated endlessly under his soulful glossolalia and melodic story telling. He spoke of a joyous “place so vast, yet a place so near,” and invited the room to dive within as he explored his vocal and instrumental abilities.

Fully refreshed and less creatively intimidated, we settled in for a full presentation of Steve Reich’s seminal 1970 work, “Drumming.” This masterpiece of minimalism was executed with total dedication and authority by ensembles So Percussion and nief-norf. Ten percussionists and two vocalists rotated on and off stage to invisible cues, either triggering or responding to phase changes (tempo, not phrase) in the endless cascade of rhythm. The piece opened with four pairs of bongo drums, which were at one point played simultaneously by nearly every member of the ensemble. Players migrated slowly through drums, marimbas and glockenspiels during the completely entrancing and time-accelerated hour.

Photo Credit: Rachel Gibson

Somehow appropriately, Television took the same stage shortly afterwards. The novel sound of a rock band was relaxing and an engaging reminder of the mid-festival alternate reality we’d be inhabiting for another day. The band shredded straight away. Touring guitarist Jimmy Rip lived up to his name as he swung his axe with muscle and precision. He played like a master bull rider, riding the edge of solos that might unhinge under lesser hands. Lead singer, guitarist and composer Tom Verlaine was simply virtuosic. As the show went on, his mastery eclipsed all else and completely ruined “guitar” for the rest of the night. The band at its peak sounded energetic and deep in the pocket. Tones pouring from the rows of VOX amplifiers were pristine and full. Eventually the extended improvisation (nearly every song) started to catch up with them. The band got a little more loose and Verlaine’s voice relaxed. It actually became a running joke how much more each consecutive song resembled the Grateful Dead. And, I’m cool with that.

Photo Credit: Rachel Gibson

The linear programming of Big Ears continued to shine at the devastatingly loud Bijou Theatre down the street. Our night closed with a performance that transcended established expectations of “heavy.” Famed Japanese improviser Keiji Haino performed with SunnO)))’s Stephen O’Malley and Australian drummer-at-large Oren Ambarchi. The stage was dwarfed by amplifiers and gorgeously lit against the ominous curtain. The set slowly rose from a primal opening affair with a piccolo flute (or something) into some extremely antagonistic guitaring with polar contrast to Verlaine’s tonality we had just witnessed. As Haino began to transition from the six string, the band began to really find its footing. Volume rose to such a level that our trust in architecture became part of the experience. O’Malley’s bass took our oil tanker through deft turns and dives. Haino stalked the stage, his perfectly rounded, body-length shock of white hair surrounding him like a spirit. Ambarchi swung the phrases in oblong circles around the chaos. Haino moved aggressively to a table with three Alesis Airsynths atop it (and some pedals). He stood above them for a few foreboding moments and then violently swung his arms and body over them like a crazed wizard possesed by an electrical current.

The sound was absolutely alive and hell-bent on obeying its master. Haino performed near three microphones. One sat center stage and waited there to hurt you like a whip. It was mixed at least 10db louder than the band one thought could be no louder, and ocasionally he would walk over to it and flog us all with primal, androgenous screams. The experience was that of transcendent S&M. To submit to it was to acknoledge, accept and embrace the pain of life. Haino didn’t give us a safe word, but I wouldn’t have used it, anyway.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.