Editor’s Note: Charlie Hayslett is retired from a career in journalism (he started out in Athens) and still keeps his hand in public relations. He puts his knowledge of our state on display from time to time in his blog, Trouble in God’s Country, at troubleingodscountry.com. This one went online Mar. 22.

Last Thursday, I posted a piece suggesting that Covid-19 might constitute a perfect storm for rural Georgia—that old age and poor health status could combine with a frail health care delivery system to put rural areas in particular jeopardy. Since then, a couple of reports have come out that support that view and bring certain health care and political realities into sharp focus.

First was a report Saturday from Kaiser Health News that documented the number of ICU beds available in virtually every U.S. county and compared those numbers with the population of people 60 and older in each of those counties. That’s not a perfect measure of an older person’s access to critical care, of course; just because there’s not an ICU bed in your home county doesn’t mean there’s not one in the next county or a nearby city. But it’s not a bad measure of the magnitude of the healthcare challenge taking shape.

The second was a report in today’s Washington Post. Philip Bump, one of the nation’s top data journalists, took the KHN data and laid it over county-level data from the 2016 presidential election between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

“Comparing the county-level data from Kaiser Health News to 2016 presidential election data,” Bump wrote, “we discovered a remarkable bit of data: About 8.3 million people who voted for Trump in 2016 live in counties where there are no ICU beds or no hospitals. That amounts to about 13 percent of the total votes Trump earned in that election, or one out of every eight votes.

“Those counties are also home to about 3.8 million people who voted for Hillary Clinton, a figure which makes up only about 5 percent of her total. Most of the counties voted for Trump by wide margins; he won them by an average of 41 points. He won 10 times as many counties with no ICU beds as did Clinton.”

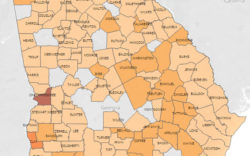

This afternoon I pulled Kaiser’s Georgia data and combined it with data from Georgia’s 2018 gubernatorial election and today’s Georgia Department of Public Health report on the number of people in the state who have tested positive for Covid-19. (As of midday today, that number was up to 600 people from 59 counties; 38 of the positives were from unknown counties.)

Overall, the situation here in Georgia is a microcosm of the national picture Bump found—and if the primary goal in this situation is to try to meet the health care needs of the entire state, state politics, as always, hovers not very far in the background and imposes a set of difficult strictures on the process.

In the 2018 gubernatorial election, Brian Kemp, the Republican nominee who ultimately won and is now governor, largely swept rural Georgia, carrying 130 counties. Of those, 83 don’t have a single ICU bed (indeed, most don’t even have hospitals). Combined, those counties have a population of 1.7 million, more than 380,000 of whom (22 percent) are over 60. So far, only 47 of the state’s 600 confirmed Covid-19 cases hail from those counties, but it seems likely those numbers will rise as testing becomes more available in rural areas.

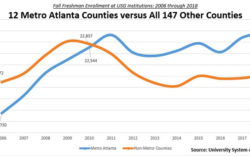

In contrast, the Democratic nominee, Stacey Abrams, dominated the state’s urban areas, which have a much younger population and much more robust health care delivery systems. Twelve of the 29 counties she carried were indeed rural (including a half-dozen southwest Georgia counties that are now in the orbit of the Covid-19 hotspot erupting in and around Albany) and also boast no ICU beds of their own. But the overwhelming majority of her support came from urban and suburban areas that are home to large health care systems with a good number of ICU beds.

The 130 counties Kemp carried are home to right at 52 percent of the state’s 60-plus population but have fewer than a third of the state’s ICU beds.

To use Philip Bump’s Washington Post framework, more than half a million Georgians who voted for Kemp— about 25 percent of his total—reside in counties without a single ICU bed. That’s true of only about 10 percent of Abrams voters.

Again, rural Georgians who fall victim to Covid-19 may well be able to get access to an ICU bed in metro Atlanta or another major city if they need it, but the current pandemic does seem to put a sharp new focus on a problem that has bedeviled the state’s Republicans since they took power at the turn of the century: how to provide health care to rural areas that constitute their political base.

For a decade now, the state’s GOP leaders have steadfastly refused to take advantage of billions of dollars in Medicaid expansion funds and presided over a steady stream of rural hospital failures. The chickens may be coming home to roost, infected by viruses.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.