Affordable housing, environmentally conscious construction and inclusionary zoning conversations have topped the progressive agenda in Athens in recent months as new elected officials prepare to take office in January.

Although forward movement in some areas has been halted for nearly a decade, a new package of legislation heading toward the mayor and commission could restart some of these long-dormant talks. One item on the list? “Kinda tiny” houses for singles, retirees and couples without kids who want a more affordable living option.

“We need a range of options that we don’t have at our disposal under our current code,” says incoming mayor Kelly Girtz. “Smaller lots and smaller homes could fit that need.”

Typical tiny homes are less than 500 square feet, but in Athens, the minimum square footage in neighborhoods zoned multifamily is 600, and the smallest new homes allowed in single-family neighborhoods are 1,000 square feet. To test what might work in Athens under the current zoning laws, the Athens Area Habitat for Humanity and U.S. Green Building Council held a “kinda tiny home” design contest a few months ago for houses between 600–800 square feet.

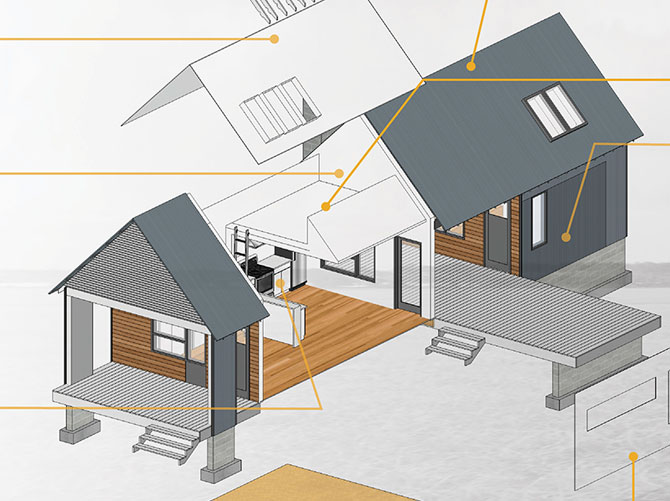

The designs were required to qualify for LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, a construction industry standard for conservation, efficiency and sustainability. Two designs received the top award: a traditional “dogtrot” design with a breezeway and a modernist design with an open floor plan.

Atlanta architects Clay Cameron, Luke Wilkinson and Josh LeFrancois designed this dogtrot house

The dogtrot approach mimics houses prevalent in the South before air conditioning, incorporating a “shotgun” layout with covered exterior spaces that increase the living area but don’t add to the heated and cooled square footage.

The modern approach focuses on a largely open, airy design with distinct spaces in the home. Functional aspects of the design—such as downspouts, the cistern of a water harvesting system and pulleys that operate shades—are features of the structural décor rather than hidden.

Smaller homes could help solve Athens’ growing affordable housing crisis, especially for singles, childless couples and retirees. Studies have shown that ordinary working people are increasingly unable to afford to live in the city. “If you can provide people with affordable housing, it creates stability, and once they have that stability, they can address other areas of their life that have needs,” says Habitat Executive Director Spencer Frye.

Frye, who also represents part of Athens in the state House of Representatives, has traveled around the state this year with the Georgia House Rural Development Council looking at affordable housing issues and solutions. “Trying to address jobs and health care in rural areas is great, but nobody has a place to live that they can afford,” he says. “The foundation has to be solid before you can build a house, and that’s true for the rest of your life, which I see over and over again in the work I do locally.”

State legislators will likely issue an affordable housing policy this fall, and Frye hopes Athens will follow suit. He and colleagues are holding onto the winning designs until then.

“It’ll be interesting to see how we can take pieces of these designs and make them come to fruition,” says David Hyde, owner of TimberBilt and chair of the U.S. Green Building Council-Athens group. “The solar incorporation and other green ideas in these designs can bring these houses way above existing code, which is exciting.”

In the meantime, Hyde is looking to other models for how to incorporate Georgia’s new energy code. In Decatur, for instance, third-party green building companies such as SK Collaborative (which sponsored the Athens Kinda Tiny Home contest) provide LEED for Homes and EarthCraft certifications, among others. The company has worked on Decatur Housing Authority apartments, a 1920s-era building in the Poncey-Highlands neighborhood in Atlanta and the Chi Phi house on Milledge Avenue, for instance.

“Hopefully, we can change the codes locally so we can create a true community with well-designed small houses,” Hyde says. “It’s straightforward if we can get local governance and mortgage lenders into the conversation.”

The issue boils down to more than changing lot sizes and minimum square footage, however. Tapping into water and sewer lines in Athens costs about $5,000, Hyde says, which is an impediment to building affordable housing.

Others have voiced concerns about changes in property taxes and county revenue based on the square footage of houses, too. Several options could encourage neighborhood development that allows for a range of lifestyles and income levels to coexist, Girtz says.

“Not all aspects of this conversation are easy, but that’s the nature of public dialogue,” he says. “We should put messy thoughts on the table and have continual discussions that produce results.”

At the same time, these issues aren’t Athens-specific. Several states are discussing ways to update their codes to accommodate “granny flats” or accessory dwelling units on one property that can be rented out or allow adults to house their aging parents nearby.

“As someone with parents who are aging, I think about the social benefits of having family close at hand,” Girtz says. “We’re ready to have this here.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.