Reporting sexual assault on a college campus is uncharted territory for many students. The multiple resources the University of Georgia provides in the way of prevention, reporting and investigating these incidents goes largely unnoticed until a student finds herself suddenly in need of these services.

In a recent open dialogue on sexual assault hosted by UGA, students raised concerns about victim-blaming, a lack of confidentiality and a general loss of faith in the system. An anonymous real-time comment box was projected on a screen:

• “I’m concerned about rapes on campus not being publicly acknowledged or properly handled.”

• “Something actually being done about the issue—not just talking about it.”

• “That students don’t have a central place to go if they have experienced sexual violence.”

Jaynce Dawkins, director for UGA’s Equal Opportunity Office and Title IX coordinator, said the theme of the discussion was a quest for a common goal: “To eliminate sexual assault and sexual misconduct at the University of Georgia.”

Representatives from every campus group and organization that has a stake in ending sexual assault—from Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention to University Housing (CAPS) to police—were in attendance.

As noted by Dawkins, UGA comprises roughly 35,000 students and 10,000 employees, but they had trouble filling a room with a 200-person capacity. This stressed her need to get the word out about the school’s various systems of support in sexual assault situations, which aren’t just a tool for investigation and punishment, but also include preventative training measures.

“Our job is not to just investigate,” Dawkins told Flagpole. Among prevention, training and awareness, Dawkins added, not many students take advantage of the resources available to them. She said there is some sort of event or training related to this topic every week—for example, regular self-defense training classes that the police department conducts for free.

What’s Confidential and What’s Not

In navigating the multitude of groups within the UGA community, it’s important for students to know there are designated places on campus that guarantee a sexual assault victim’s right of confidentiality and other places where there is no protected confidentiality. Telling your professor, for instance, is not protected.

During UGA’s open dialogue, Jane Westpheling, a genetics professor, said that in her last faculty meeting the professors were directed that they “may not have confidential conversations with students who come to [them] as victims of sexual assault… That concerns me greatly.”

She added that in teaching both large and small classes, as well as being an academic adviser, she develops close relationships with her students. “Providing a safe haven for someone to come tell you that they’ve been assaulted is absolutely imperative to reporting these issues,” Westpheling said. “The notion that I can’t have a confidential conversation with someone doesn’t make any sense to me.”

However, there is an exception to that rule. If you inform the EOO prior to confiding in your professor and request that it be confidential, your teacher can be given the power of confidentiality.

The locations on campus where a victim of sexual assault can be guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality include: RSVP, CAPS, Health Center Medical Clinicians, Student Support Services and Ombudspersons. In addition, the North Georgia Cottage, located behind the Athens-Clarke County police station off Lexington Road, is an essential off-campus resource for victims of sexual assault; it also provides a 24-hour crisis hotline and is completely confidential.

In most cases, the confidentiality requests of a student who files a report with the EOO will be honored, except in situations where it’s determined to be a “campus safety issue.” Those situations can range from multiple accusations of one perpetrator, an incident comprised of a group of perpetrators, if the victim believes she was drugged or if the incident happened on what is considered a “hot spot” on campus. If it has to be investigated, the student will be informed, but will have no control over stopping the proceedings.

The EOO Takes Over

In April of 2011, the Department of Education sent a letter to universities and colleges nationwide to spell out how institutions regulated under Title IX should investigate alleged acts of sexual violence. That’s when the EOO took over these investigations from the Office of Student Conduct.

As the Title IX coordinator, Dawkins, with the EOO, is responsible for ensuring compliance with UGA’s Non-Discrimination and Anti-Harassment policy. “We are not an advocate. We don’t advocate for the accuser or the accused,” Dawkins told Flagpole. “We are charged with conducting a fair and impartial process and determine by a preponderance of the evidence that we collect whether there’s been a violation of our policy.”

The EOO investigation is separate and distinct from a police investigation. It uses the “preponderance of the evidence standard” meaning that, as mentioned by one of the EOO investigators, “50 percent plus a feather.” Basically, the investigator can determine that there was a violation if the evidence suggests that it was more likely than not to have occurred.

These cases rarely just come down to “he-said, she-said,” according to Dawkins. And these investigations take into account more than just the testimony of the two students involved. Evidence that is used includes security camera and digital communications. If a violation is found, the weight of the evidence will come into play during sanctions.

According to UGA’s policy, the school can take interim protective measures—even prior to the determination of violation—when not taking such measures would “constitute a threat to safety and well-being of the complainant” or other members of UGA’s community. Interim measures include reassigning housing, prohibiting contact with the complainant and bans on entering certain university property.

Since the DOE letter, 50 lawsuits have been filed across the country by alleged perpetrators who claim the adjudication process based on this standard of evidence violates their rights to due process. None of these lawsuits involve UGA.

Earlier this year, Flagpole reported on the experiences of former UGA student Katherine Garcia, who described being sexually assaulted at a fraternity on campus. Shortly after that, Kristopher Stephens, EOO associate director and one of the investigators, contacted her. “I was kind of confused because I felt like I was very, very open in my story in Flagpole. I didn’t feel like I had anything else to tell,” Garcia said. “I was kind of frustrated that I was having to go through everything one more time, but now in retrospect I realize how important it was to have everything on record.

“I think it’s great that we have the numbers and the statistics and that more people are reporting this,” she said.

Reports Through the Roof

“If we don’t get the information, we don’t know how to respond. We don’t know where to respond,” said Deanna Walters, a coordinator for RSVP, at the open dialogue. Other hosts of the dialogue echoed the need for more data and accurate sexual assault numbers, which segued into more discussion regarding students’ awareness of confidential reporting centers.

As previously reported by Flagpole, sexual assaults on campus are most likely to occur in the “Red Zone”—the time period between the beginning of school and Thanksgiving when students are most at risk. And the frequency of these incidents, not just within the Red Zone, indicates that freshmen and sophomores are most at risk.

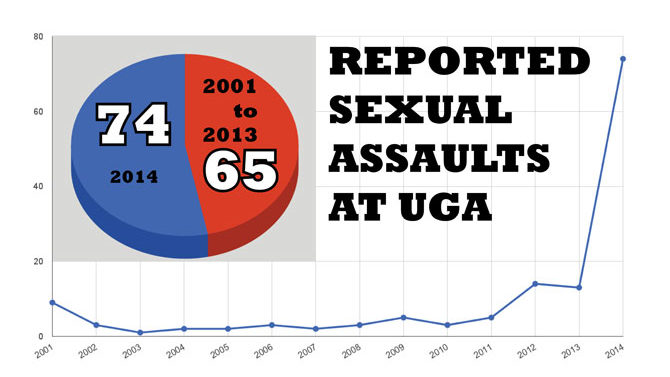

In recent years, UGA police began accepting anonymous reporting—including those reports made by a third party. The numbers have since gone through the roof. This year alone, there have been more reported sexual assaults than in the last 13 years combined. Of the 74 reported incidents this year, 60 of them were rape.

From the time EOO took over Title IX investigations in 2012, there have been a total of 87 cases, which includes incidents of sexual harassment and other Title IX areas. However, Dawkins said, “Any of these that were informally resolved would not be a sexual assault.” Pursuant to federal guidelines, informal resolutions of sexual assault cases are not permitted. A total of 20 of these cases were informally resolved, which means that a maximum of 67 of these cases could have been sexual assault. A Georgia Open Records Act request was submitted for these sexual assault specific numbers, but Dawkins told Flagpole that pinpointing the exact number of cases would take extra time—numbers were not available as of press time. Regardless, out of all the closed EOO Title IX investigations, more than half of these cases conclude that no violation occurred, despite the low standard of evidence.

What’s most important, Dawkins said, is that students are “more comfortable reporting” and “more knowledgeable” on where to report. “Ideally, we want to have no investigations and no reports because there are none,” she said, adding that she hopes efforts to educate the UGA community will take root and eliminate some sexual assaults.

“We’re working on it, and I just never want to be content with where we are, because we can always do better,” Dawkins said. “I hope every day we do it better.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.