On a recent evening, a large crowd gathered at the Melting Point to hear older Athenians share stories about pivotal moments in their lives where racism was front and center.

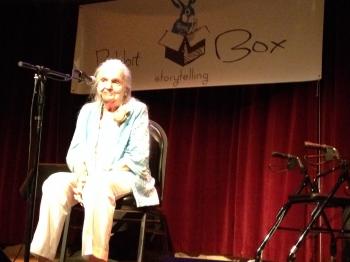

The event, “Silver Box—My Life in Black and White,” was put on by Rabbit Box, a monthly storytelling series where people in the Athens area share their real life tales related to the month’s theme.

After a quick introduction by master of ceremonies Mary Whitehead, the stories began. Don Johnson’s pivotal racial experience occurred in 1964, the year that the Civil Rights Act was enacted. It was also the year that Lemuel Augustus Penn, a decorated WWII veteran and a U.S. Army Reserve officer, was traveling with two other black officers from Fort Benning to Washington DC. Stopping in Athens near the Confederate Memorial to switch drivers, the men attracted the notice of James Lackey and his two passengers, all members of the Klan. They followed Penn’s car and at the Broad River Bridge in Madison County they killed him with a sawed off shotgun.

Johnson’s father was the solicitor general at that time and was called upon to prosecute. Johnson said his father wanted his family to come to the trial, which was unusual request. Set in the Danielsville Courthouse, it “looked like a scene from To Kill a Mockingbird.” The heat was sweltering, the courthouse was segregated and all of the big press was covering the trial. While telling his story, Johnson was allowed to read from his father’s powerful and moving closing argument in the case. In it, he said the “only thing they (the murderers) knew was that he (Penn) was born a Negro”… and that this was “just as much an assassination as when President Kennedy was shot with a rifle just a year ago.” Johnson’s voice continued to rise as he went on with his father’s remarks, ending with the statement that the State of Georgia’s honor was on trial that day.

“The State of Georgia’s honor was lost that day,” Johnson said sadly; the jury failed to find Penn’s killers guilty.

Robert Ayers’ narrative took place when he was teenager, just as Johnson’s had. His family lived in a parsonage in North Carolina and employed a young black woman, Ray, as a cook. One day “The penny dropped, as the British say.” In other words, his “eyes came open.” Ayers was on the front porch watching Ray cautiously cross the street on her way home, when he heard a car screeching and speeding up. “Ray didn’t make it across that street,” he said. “Do you know, that guy was the son of the richest man in town, in a new car, and cursing her for getting in his way?” The police came and refused to charge the driver and even threatened to charge the wounded Ray with jay walking. An ambulance was called but never came, and Ayers’ father drove Ray to their family physician for treatment. This experience opened Ayers’ eyes to injustice, and he sees it as the beginning of his commitment to “bringing society to its senses.”

Valdon Daniel, also offered a story from his youth. He was born and raised in Athens. When he was 12, he got a job working in Akins Grocery. Daniel learned the ways of the store, carried groceries to black customers and was excellent with math. He earned one dollar a day. The owners then hired a white woman to work at the store on its busy Saturdays. Eventually, Daniel discovered that the white woman was being paid five dollars a day, doing less than he, while he still earned only one dollar. One very busy Saturday, when the store was “packed out” with customers, Daniel asked the owner if he could also work the register and earn five dollars a day. He was told that he could leave, and he did. He waited one hour, two hours, two and half-before he finally received the call telling him he would be paid the five dollars, could he please come back to work. “Timing is everything,” Daniel concluded with a smile.

Sydney Bacchus told a story not about her youth but about her battle of recent years with Clarke County over the landfill expansion. Citing numerous unkept promises concerning the landfill made by Clarke County officials through the years, she noted that it is the predominantly black residents of the Dunlap Road community and Bishops Grove Church who are the primary victims of expansion and who are exposed to the stench of sewage sludge composted on the perimeter of the facility. She noted that this situation, something “whites would not tolerate,” was a modern day “substitution for lynchings.”

Zena Johnson was 16 when she got her first job at the Sears and Roebuck in Columbia, SC. During the busy Christmas holiday she worked in the toy department and had her first experiences with racism. In spite of having to wait in very long lines, few whites would come to her register, where the line was always short. If they did, they often set their money on the counter, so as not to touch her hands. Perhaps, she said, they were afraid “the black would rub off on them.” Earnest Thompson shared a life story in Charleston, SC. during the ‘40s. The unwritten rule was, though black and white children played together, they were never to enter each other’s yards. There was an “over the fence sort of relationship” between the racially different neighbors.

Thompson’s pivotal experience began one day when he found a new white neighbor, whom his mother had described as “poor white trash” and instructed him to stay away from, in the Thompson family’s yard picking azaleas. Tensions escalated as the child hurled “the ‘n’ word” and ended with Thompson throwing a rock, which hit the child in the chest. Thompson eventually found himself, filled with fear, in the courthouse with his mom after charges were pressed. Ultimately, Thompson had only to swear that he would “never go in the Kramer yard,” something he hadn’t done to begin with.

Photo Credit: Barbette Houser

Sylvia Priest described a trip she took as a California basketball coach, loading up her girls’ team in her Plymouth station wagon and driving them for four hours down Route 66 for a match. That night, they pulled into a motel lot looking for a room for the night, and Priest was told, “Our motel is full.” She thought nothing of it until she got the same response at two more motels. One young black girl was on the team and in her car. The group of travelers were ultimately directed to a different neighborhood to find accommodations.“Anyway,” she stated, “I was black for one night.”

Mony Abrol was called in for a job interview in a big shipyard in Brooklyn. Armed with qualifications and wearing a big smile and his best suit, he eagerly opened the door to the office, only to find the manager there looking at him with a face “like a deer in the headlights.” After an interview which lasted about 40 seconds, he was dismissed. Only minutes later, while Abrol was sitting in the shipyard mulling over his recent experience of being judged by his color, he witnessed a heavy steel girder that was unbalanced in a crane’s grip, hovering over four men. He shouted to the endangered men to dive to the left and saved them from injury or worse. The CEO of the company witnessed the event his eventy, and Mony ended up getting the job after all. In a 15-minute span, he had “met a racist bigot, used my knowledge and met a perfect Southern gentleman.”

Ivan Sumner experienced a moment of intense racial awareness as a young man hitchhiking and then traveling by bus from Detroit to Florida in 1961, when he had to stop at the Atlanta bus terminal. Unwittingly, he found himself on the “black” instead of the “white” side of the strictly segregated station. He only became aware of this mistake after he was not helped at the counter for a long period. The conflicting emotions and discomfort he felt after realizing he was breaking the law and convention with his mistake are something that stayed with him, albeit repressed, for decades.

The stories pulled out of the Rabbit Box on this particular evening were powerful to both the listeners and the tellers and involved a myriad of experiences and feelings, many of them ugly, painful and life-changing. We all have a story we need to tell. How fortunate that we have this venue in Athens to give us a voice.

Rabbit Box’s next event will be “Rabbit Box with Art Rocks Athens” and will take place on Wednesday, June 11 at 7 pm at The Melting Point. Visit www.rabbitbox.org for more information.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.