When my wife and I first became parents, our son’s godparents took pure glee in giving our child toys that played songs and made noise. As all parents know, watching one’s child take delight in pushing a button and producing a sound is a beautiful thing… for about five minutes. After that it becomes a hellish, teeth-gnashing ordeal of “O Susannah†and “It’s a Small World†on an endless loop that haunts your dreams. If you ever want to see something funny, speak the words “Barney’s Magic Banjo†and watch us convulse.

One night my wife and I, sleep-deprived and staring with the eyes of shellshocked Vietnam vets, decided that we would just never tell our son about batteries. When the noise toys finally stopped working, we’d just shrug and commiserate with the boy over their untimely demise. Then one of us, I don’t remember who, predicted that one day our son would take this as a challenge and decide to devote his life to inventing a small, replaceable power source, and that the day after he unveiled his triumph to the world he’d come after us and kill us both, probably with Barney’s Magic Banjo.

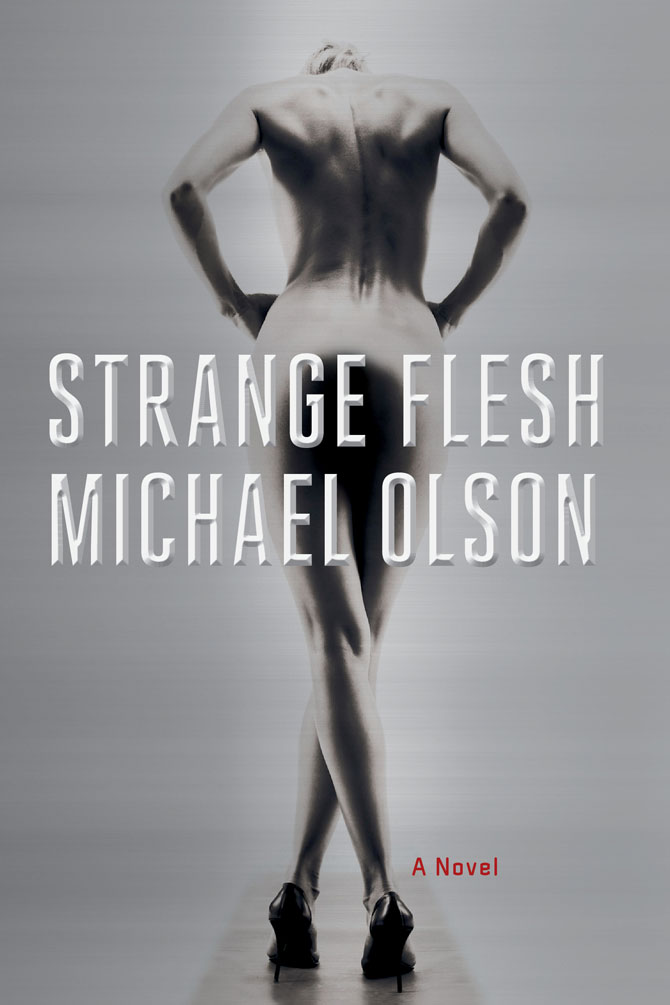

Michael Olson’s debut novel Strange Flesh (Simon & Schuster, 2012) feels much like that, the product of a writer working for years on something that’s already been invented. Had his cyberpunk noir, packed with techno-fetishism and loads of the other kinds, come out 10 or 15 years ago, I’d be calling it brilliant. Today, however, it’s a decent novel that revisits ground trampled hard and flat by too many previous travelers.

James Pryce is a world-weary detective of the 21st-century variety. An operative for a sky-high-tech cyber-security firm so bleeding-edge that the NSA calls on them for help, he spends his off-hours drowning his sorrows, not in a bottle but in disastrous hookups with women he meets in online sex sites, which typically end with Pryce getting beaten up and robbed. Like any good noir hero, however, the cause of Pryce’s self-destructive spiral is a woman, in this case Blythe Randall, a patrician beauty from his Harvard days—distant, melancholy and attached in a definitely unwholesome way to her twin brother Blake. Blythe is the one that got away, the one who messed Pryce up, and so it is a shock when the Randall twins contact Pryce’s firm and ask for him personally.

The Randalls contract Pryce to track down their black-sheep half-brother, a cyber-artist with a grudge against them and a stylized suicide video that is most certainly faked, showing Billy Randall de-rezzing into a Second Life-type simulation world as he threatens to bring his siblings and their telecommunications empire down. Pryce goes undercover at the headquarters of the world provider, a tech collective of eclectic gamers and artists, and finds himself entwined with a group working on a project so outrageous it promises to revolutionize both virtual reality and sex itself. Meanwhile, his pursuit of Billy leads him into his quarry’s deepest obsession, realizing the darkest dreams of the Marquis de Sade in literal, unflinching and lethal reality.

The book is hardcore punk noir from start to finish, with wonderfully graphic depictions of sex and violence, which often happen at the same time. Olson’s biggest misfortune, however, is that the elements of his novel no longer have the power to shock that they should. There is no gee-whiz factor in depicting immersive sim-worlds to an audience now weaned on World of Warcraft—hell, even William Gibson has stopped writing cyberpunk—nor is there much ewww to be found in the BDSM that pervades Olson’s novel when it shares shelf-space with Fifty Shades of Grey, currently being read by millions of closet-kinky housewives across the country. And while cyberpunk and noir go together like a fist and a jaw, the current state of the genre is much further out than Olson goes here—take a look at Richard K. Morgan’s Takeshi Kovacs novels, for example, which center on a detective who downloads himself into other people’s bodies.

Maybe I’m jaded. I’ve been reading about cyberpunk for 24 years and about sex for much longer than that, and I forget that not everyone has been immersed in this stuff like I have. Strange Flesh may be more shocking to some than it was to me, and for those people I applaud their willingness to take a walk on the wild side. For my part, I’ll be interested in seeing what Michael Olson does next, now that he has invented the battery.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.