We who reside in college towns are fond of saying they are great places to live when the students aren’t around, but, in fact, the welcome silence that signals their departure would probably get to be as deafening as their presence if they stayed away too long. Well, maybe not, but many of us would probably miss them eventually, if only for the free entertainment they offer when at play.

There is a problem with way too much of that play, however, in that it is tied to a distressingly high mortality and serious-injury rate among middle-class youths who should just be getting primed for the prime of their lives. There is quite enough blame for this alarming trend to go around, but for now, a good portion of it is being laid squarely at the beer-stained steps of college fraternity houses. A recent blockbuster of an article/expose by Caitlin Flanagan in The Atlantic draws on a year’s worth of research on “Greek houses” and promises to reveal “their endemic, lurid, sometimes tragic problems—and a sophisticated system for shifting the blame.” Sadly enough, it delivers on all counts.

Flanagan suggests that while fraternities had stood as essential pillars of privilege supporting the very Establishment assailed by the shaggy sandal-shod student protestors of the 1960s and early 1970s, the iconic 1978 film Animal House signaled not only a resurgence of frathood, but a dramatic reversal of how it was perceived as well. In short, Animal House stripped the student impulse to rebel of its social and ideological commitments and entanglements and redefined rebellion as the slavish pursuit of personal-pleasure via outrageous, irresponsible and thoroughly self-indulgent behavior.

Thanks in no small part to the student lefties of the previous decade, the doctrine of in loco parentis was now a goner on campus, and the ensuing contraction of university supervision of collegians’ conduct left plenty of room for Freddy Frat to engage in all manner of socially objectionable behavior. Yet the caricatured, seemingly harmless antics served up by Animal House managed to envelop frat-boy audacity in a disarming, guilt-and-consequence-free bubble.

Curiously enough, the kickoff exhibit for Flanagan’s case actually evokes powerful memories of the antics of Bluto, Otter, and their fellow Delta Tau Chis. In Flanagan’s masterful retelling, one evening in May, 2011 whilst on the deck of the ATO house at Marshall University and “under the influence of powerful inebriants,” one Travis Hughes decided it would be “an excellent idea” to “shove a bottle rocket up his ass and blast it into the sweet night air.” Unfortunately, the influence of the aforementioned inebriants apparently led young Mr. Hughes to “misjudge the relative tightness of a 20-year-old sphincter and the propulsive reliability of a 20-cent bottle rocket. What followed ignition was not the bright report of a successful blastoff, but the muffled thud of fire in the hole.”

More unfortunately still, also at the scene was an only slightly less inebriated Louis Helmburg III, a sub on the Marshall Thundering Herd baseball team, who, like Hughes, was not actually affiliated with the brotherhood of ATO. Helmburg decided to capture Hughes’s daring exploit via cell-phone video and positioned himself in what proved to be imprudent physical proximity to the actual launch pad, so to speak. Thus it was that “when the bottle rocket exploded in Hughes’s rectum, Helmburg was seized by the kind of battlefield panic that has claimed brave men from outfits far more illustrious than even the Thundering Herd. Terrified, he staggered away from the human bomb and fell off the deck.

Fortunately for him, and adding to the Chaplinesque aspect of the night’s miseries, the deck was no more than four feet off the ground, but such was the urgency of his escape that he managed to get himself wedged between the structure and an air-conditioning unit, sustaining injuries that would require medical attention.”

Helmburg’s wounds were sufficient to truncate his baseball season, and he filed suit against the ATO national organization, the litigation of which would consume the next 30 months before an out-of-court settlement was reached.

The temptation to chuckle at this fiasco, which amounts to life-imitating art (provided Animal House be art), is well nigh irresistible, much as it was with the notorious “butt chugging” craze that swept across ol’ Rocky Top a while back. Yet, as Flanagan recounts vividly, the outcomes of such incidents may turn out to be anything but funny.

A case in point is that of Amanda Andaverde, a 19-year-old sophomore at the University of Idaho, who had just pledged Tri-Delt in August, 2009. Andaverde and her sorority sisters kicked off a night of drinking at the Sigma Chi house before moving on to SAE, where additional libations and further loosened inhibitions led her to the third-floor sleeping porch and onto the bunk of one Joseph Jody Cook. Attempting to roll over in the middle of the night, Amanda fell 25 feet onto a cement surface, suffering permanent brain damage that left her seriously impaired physically. If this account were not sufficiently disconcerting, Flanagan discovered that Amanda’s was actually the second such fall from an upper story of a University of Idaho fraternity house in a two-week period.

Two months later and only eight miles away at Washington State University, another student fell from the third story of a frat house. Owing to their proximity, the two campuses sustained a common student-party culture that was good for at least three similarly serious falls from September through November 2012 alone.

If you are thinking at this point that these terrible mishaps might be geographically concentrated, think again. Flanagan quickly comes up with five more such incidents in 2012, scattered cross-country from Berkeley to Ithaca, and shows there were at least eight more coast-to-coast in the summer and fall of 2013.

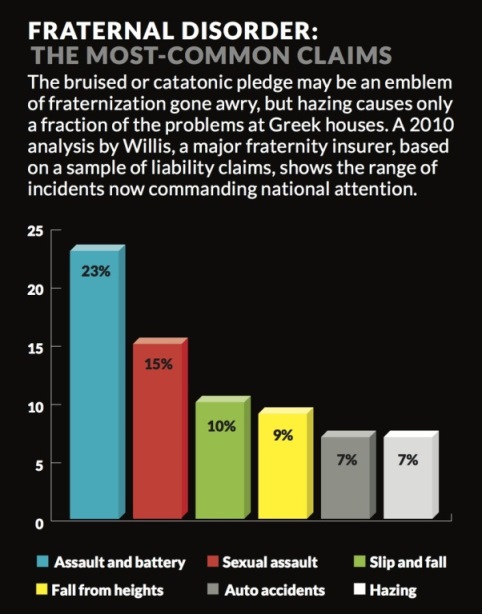

We have focused thus far only on serious accidents involving falls and not the myriad examples of physical and sexual assaults or fatal or near-fatal incidents of alcohol poisoning whose tracks converge at the frat house door. Ironically enough, for all the ongoing furor over hazing, according to a 2010 survey, it accounts for only 7 percent of the claims filed against fraternities nationwide compared to the 9 percent triggered by falls from height, and more worrisome still, hazing suits add up to less than half the share (15 percent) of claims premised on sexual assault and less than a third of those (23 percent) involving assault and battery. Overall, recent research by a pair of Bloomberg writers shows that, at the very least, more than 60 people have died in fraternity-related incidents since 2005.

It is small wonder, then, that liability insurance became difficult for frats to come by at any price, beginning back in the 1980s, when industry experts named fraternities as the sixth-worst insurance risk in the country, and individual insurers largely pulled their coverage en masse. The upshot has been the formation of trust-like collective self-insurance arrangements such as the Fraternal Information and Programming Group (FIPG), which currently lists 32 national member fraternities.

Other similarly specialized coverage arrangements have emerged as well. In either case, it is important to know that the bottom line for this sort of coverage amounts largely to limiting the liability exposure of the national organization, and in actual practice, it sometimes accomplishes that by actually transferring that exposure to members of individual chapters where claims have arisen.

In particular, chapters who do not pay for the liability limitation inherent in securing a third-party vendor of alcohol at chapter events manage to facilitate drinking by imposing what appear to be some highly unrealistic, even unworkable, stratagems, such as the “BYO-plan,”

The general UGA version of which, as of 2008, at least, is described here, whereby members of drinking age, who may well represent a minority within the group, are permitted to come to designated limited-attendance events bearing no more than a six-pack of beer, which must then be tagged with the bearer’s name and doled out solely to him by fellow members, who may or may not be of age themselves. Sharing his brew even with brothers of legal drinking age puts him in violation of the fraternity’s alcohol policy and should some injury or harm come either to the recipient of his generosity or should said recipient cause harm to others, poor Bubba Six-Pack can easily go from a cherished member of the brotherhood to a toxic vulnerability in its midst.

Should the failure of a BYO or some similar protective system precede someone’s injury or death, the brothers are generally on orders to stay mum until the fraternity’s insurance interrogators arrive, at which time they are warmly encouraged to sing to these ostensible guardians of their interests like meth-buzzed canaries on truth serum, fully and candidly implicating themselves and others as violators of the national organization’s precisely worded and literally interpreted official alcohol policies.

If the anticipated damage suit materializes, these unsuspecting lads who thought the fraternity’s lawyers were supposed to be defending them can find that, as far as the national organization is concerned, the purportedly eternal benefits of brotherhood are now forfeit and the bonds conferred by the secret handshake annulled, leaving them pretty much on their lonesome to face the pitiless fire of the plaintiff’s legal sharpshooters.

The ol’ Bloviator has no way of knowing which fraternities might approach this issue differently, but he does find Flanagan’s research exhaustive and her general conclusions persuasive. Hopefully, parents of fraternity members or of young men who are about to be are already familiar with the organization in question’s procedures for handling such liabilities, but if not, close attention to the following paragraph from Flanagan might be advisable:

“I’ve recovered millions and millions of dollars from homeowners’ policies,” a top fraternal plaintiff’s attorney told me. For that is how many of the claims against boys who violate the strict policies are paid: from their parents’ homeowners’ insurance. As for the exorbitant cost of providing the young man with a legal defense for the civil case (in which, of course, there are no public defenders), that is money he and his parents are going to have to scramble to come up with, perhaps transforming the family home into an ATM to do it. The financial consequences of fraternity membership can be devastating, and they devolve not on the 18-year-old “man” but on his planning-for-retirement parents.

To see young men who should be held “100 percent accountable for their actions… perhaps for the first time in their lives,” by the very outfit that seemed to offer tacit assurances of four carefree years of self-indulgent irresponsibility is to confront irony in its grimmest sense. The primary reason national fraternities have embraced such a byzantine and deceptive CYA strategy comes through in the observations of Douglas Fierberg, the nation’s premier plaintiff’s attorney in “fraternity-related litigation,” who contends that the frat system is “the largest industry in this country directly involved in the provision of alcohol to underage people.”

Sure enough, sifting through “hundreds of fraternity incident reports,” Flanagan could find not a single one relating to “an event where massive amounts of alcohol weren’t part of the problem.” (This suggests what a great idea it would be to plug firearms into the campus equation, don’t you think?) The extent to which maximized access to alcohol is likely to factor into any single 17- or 18-year-old boy’s decision to rush into fraternity rush is clearly debatable, but the probability that it factors collectively into many such decisions most assuredly is not. Thus, the possibility that a key factor in their attractiveness may someday pose a serious threat to their survival led fraternities to adopt an effective, if cold-blooded, strategy for minimizing or transferring the risk posed by their alcohol-centric culture and existence.

Having brutalized the Greek brotherhood nonstop thus far, however, it is not only unfair but a downright cop-out to leave them saddled with all of the blame for the serious alcohol problems that are so blatantly obvious on so many college campuses. It is utterly foolish to think that most freshmen are downing their first gulp of beer after they hit campus, even if being there undeniably expands their gulping opportunities, and that brings us to the matter of paternal attitudes toward underage drinking.

The O.B. has argued more than once that the much-lamented “generation gap” said to have separated the youth of his era from their Depression-reared, war-tested moms and dads would be infinitely preferable to today’s buddy-buddy, just-one-of-the-guys/girls parenting model, which one strongly suspects in this case may appeal to the parents as a means of reliving their college years vicariously through their kids.

For example, the Ol’ Bloviator is both shocked and sorely dismayed to see so many of today’s parents not simply condoning but finding amusement in seeing their 18-year-olds flashing fake IDs and generally plunging head-first into Lake Alcohol as if it were in danger of drying up in the next few days, much less before they reach 21. He can’t help but wonder how heartening such parents would find it to check out the 2 a.m. scene when their over-indulged and definitely over-served freshmen are staggering back toward what they hope is their dorm or, better yet, take stock of their progeny as they drag themselves into an afternoon class still in possession of a 10-ton hangover and smelling as if they had just gargled a 40-ounce Natty Light. In some cases, even “parents’ weekends,” which were once stilted and admittedly boring affairs fueled primarily by fruit punch and stale cookies, are now lubricated by a steady current of booze.

Although it is rumored that Dean Noah recently contacted the Physics Department to see if gopher wood will float on beer, the apparent reluctance of most campus administrators to address this problem head-on may well arise from concerns about sending negative vibes to youngsters whose relatively affluent backgrounds indicate that the rising costs of being a collegian are likely to be no object to their parents, who write checks for donations as well as fees.Meanwhile, those parents, along with other alums, may also convince themselves that excessive drinking is no bigger threat to student health or the university’s educational mission now than it was in their day.

Take it from a grizzled, 40-year veteran who was actually around back then and, after serving on six campuses, is still around today, this university and the overwhelming majority of its peer institutions are awash in alcohol as never before. Trying to deny or downplay this grim reality or duck the responsibility it conveys is tantamount to whistling past a graveyard, one, in this case, where an increasing number of occupants are unfortunately and unnecessarily arriving way too early.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.