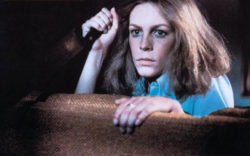

Aaron Johnson and Glenn Close

ALBERT NOBBS (R) A hotel waiter in 19th-century Dublin, Albert Nobbs (Glenn Close), a woman, has long lived a life of deception and subterfuge by pretending to be a man in order to work. Her life is blind-sided when a house painter, Hubert (Janet McTeer), working at the hotel for a brief time, discovers Albert’s secret. Hubert also has a secret of his own. Meanwhile, Albert yearns for the companionship of a maid at the hotel, Helen (Mia Wasikowska), hoping that she will marry him. But Helen has eyes for an uncouth Irish lad, Joe (Aaron Johnson), who promises to take her to America with him.

Albert Nobbs is a stiff. Based on a short story by George Moore and a subsequent play, Albert Nobbs theoretically has all of the dramatic ingredients to make for a brilliant movie. Close originally played the character of Nobbs on stage in 1982 and long wanted to bring the production to the big screen. Outside of some strong performances by the supporting cast—Wasikowska, McTeer and Brendan Gleeson—Albert Nobbs never coalesces into the first-class prestige drama it was undoubtedly designed to be. Director Rodrigo GarcÃa, son of novelist Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez, never feels sure of himself with the material or with the performances. Close’s mannered acting (she was nominated for an Oscar this year for it) may have once convinced onstage, but here she borders on the grotesque, looking bizarrely unnatural when acting opposite more natural performers. This contrast in styles could have made for something interesting with a strong director behind the camera, but GarcÃa seems tone deaf through much of it, unable to figure out whether to draw out poignancy or humor in a scene, such as the moment when Albert and Hubert don dresses and walk through the streets as women. One can’t help but wonder what kind of insight and true craftsmanship James Ivory and Ismael Merchant (Howard’s End, Remains of the Day) could have brought to this in their heyday. The movie raises the question: Why was this made for the big screen in the first place? There’s not a cinematic bone in its long, starchy 113 minutes. When a transition whip pan makes for the biggest movie moment, you’re in trouble. It would have made a better fit for the small screen. Then again, dramatic television hasn’t come off as bloodless as this in over a decade.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.