It has been 60 years since civil rights actions called “Freedom Rides” began on May 4, 1961. The rides involved interracial groups of activists who rode interstate buses through the South to challenge the American apartheid of Jim Crow segregation laws then in effect in darkest Dixie below the Mason-Dixon line.

The first of the 1961 Freedom Rides began in Washington, DC on May 4, 1961, and ended in New Orleans on May 17. The rides spotlighted the injustice of segregation in buses, waiting rooms and restaurants in the Deep South six decades ago. On May 13, 1961, the Freedom Riders stopped at the downtown Athens bus station during their perilous journey down the highway of history.

Freedom Riders, both black and white, endured beatings, jailings and threats from racist mobs during the rides, but they persisted in their defiance of unjust laws in the American South. Legendary civil rights activist John Lewis was beaten and bloodied in both South Carolina and Alabama during the 1961 Freedom Rides four years before he was nearly killed by Alabama cops during the “Bloody Sunday” protests for voting rights in that state in 1965. Lewis later became a Georgia congressman who was the conscience of Capitol Hill until his death last year.

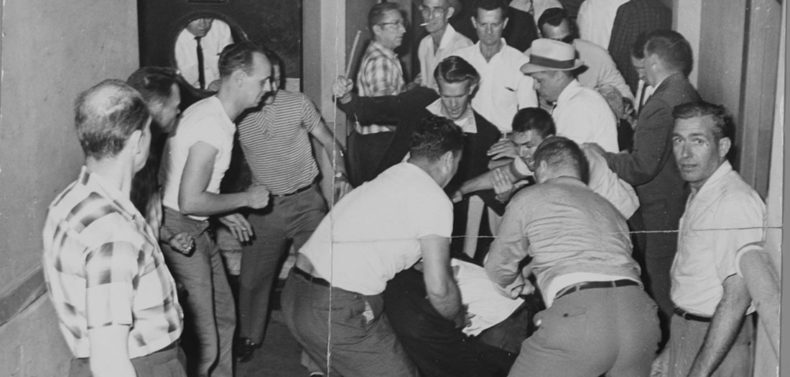

When the Freedom Riders stopped in Athens in 1961, they were on the way to Atlanta, where they met with Martin Luther King Jr. They had earlier endured violence on their journey through the South, and they could have expected the same here in Athens, where just months before the Freedom Rides a racist mob of townspeople, Klan agitators and college students had rioted against the desegregation of the University of Georgia. Local police used tear gas to quell the white rioters who were angry over the admission of black students Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter (now the journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault).

Though fearing more racist violence in Athens, the Freedom Riders were pleasantly surprised during their stop here. At the Athens bus station, “Freedom Riders were served at the lunch counter without question,” recalled James Peck, a white man who joined the integrated rides through the segregated South. “A person viewing the Athens desegregated lunch counter and waiting room during our 15-minute rest stop might have imagined himself at a rest stop up North rather than deep in Georgia.” The Athens bus station is now the Chuck’s Fish restaurant, fittingly named for white civil rights attorney Chuck Morgan, who died in 2009.

Though the Freedom Rides were big news across America and around the world, no local reporters were on hand when the riders stopped in Athens. When the Freedom Riders were attacked by mobs who firebombed their bus in Alabama, photos of the burning bus were front-page fodder nationally and internationally, but not here in Athens.

Photos and news accounts of the Mother’s Day melee in Alabama became iconic memories of the freedom movement, but in 1961 the local Athens Banner-Herald newspaper marginalized the event by running only a small Associated Press story that made no mention and included no photos of the bus that had been torched by a mob in our neighboring state of Alabama. An Athens Banner-Herald editorial at the time was headlined “Liberals Going Too Far With Racial Legislation.” The editorial blamed “so-called liberals in Congress” for being “more interested in embarrassing the South than in trying to solve the civil rights problem.”

Decades after their journey for justice, Freedom Riders Hank Thomas and John Lewis returned to Athens in 2003 to speak at the downtown Human Rights Festival. Thomas, a Vietnam veteran, said, “It should not take a war to make us understand that we’re all Americans.” Lewis told the cheering crowd, “We all live in the same house. We’re one people. We’re one family.” Their sentiments were echoed in 2011, when Hunter-Gault spoke here in Athens on the 50th anniversary of the university’s racial integration. She spoke words that are more relevant than ever today: “If people are informed, they will do the right thing. It’s when they are not informed that they become hostages to prejudice.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.