You know that antebellum, white-columned mansion sitting back off Prince Avenue where Pope Street rises behind Emmanuel Episcopal Church? It was built by Mary Ann Lamar Cobb and her husband, Howell, and it was brand new when the aftermath of the Panic of 1837 wiped out Howell’s wealth. His father, John Addison Cobb, using credit and money from his plantations, was a plunger and a developer—our first intown neighborhood, Cobbham, being among his undertakings. Howell had co-signed his father’s notes, and the Panic—sort of like a stock market crash—resulted in the banks’ eventual foreclosures on the Cobbs, forcing them to sell all their considerable property, including the Carters: George and Silva and their children Aggy, Polly, Eliza, Robert, Nelson and Ellick.

“The Carters were likely told that their public auction, along with that of the beautiful furniture, was necessary to cover the debts of the bankrupt Cobb family. They likely were told to be patient and behave. But all the guises of paternalism and the imagined bonds of affection fell to ash when human beings were forced to stand on a grand front porch of an exquisite hilltop mansion. Then they had to accept that the people they had known and served for a lifetime had the power and the intention to sell them along with other pieces of valuable but ultimately disposable property.”

This passage is quoted from Seen/Unseen: Hidden Lives in a Community of Enslaved Georgians, just published by the University of Georgia Press.

This meticulously documented scholarly work is an attempt to delve into the past of a wealthy, prominent Athens and Georgia family and to tease out clues to the lives of the people they owned—difficult because of the paucity of written details left by people who generally were kept illiterate, but possible in this case because the Lamar-Cobb families wrote extensively among themselves, often mentioning the people they owned, and some of the enslaved also wrote letters that were preserved in the family archives, now in UGA’s Hargrett Library. The authors include a rich selection of excerpts from those letters, so that the owners and the owned tell the story of what it was like in Athens and on the plantations during slavery.

The Lamars and the Cobbs were two of the wealthiest families in Georgia, and their fortunes were united by Mary Ann and Howell’s marriage—though not completely: Mary Ann had one of the earliest prenuptial agreements, and it kept her assets in her name and thus protected them from her husband’s financial ruin.

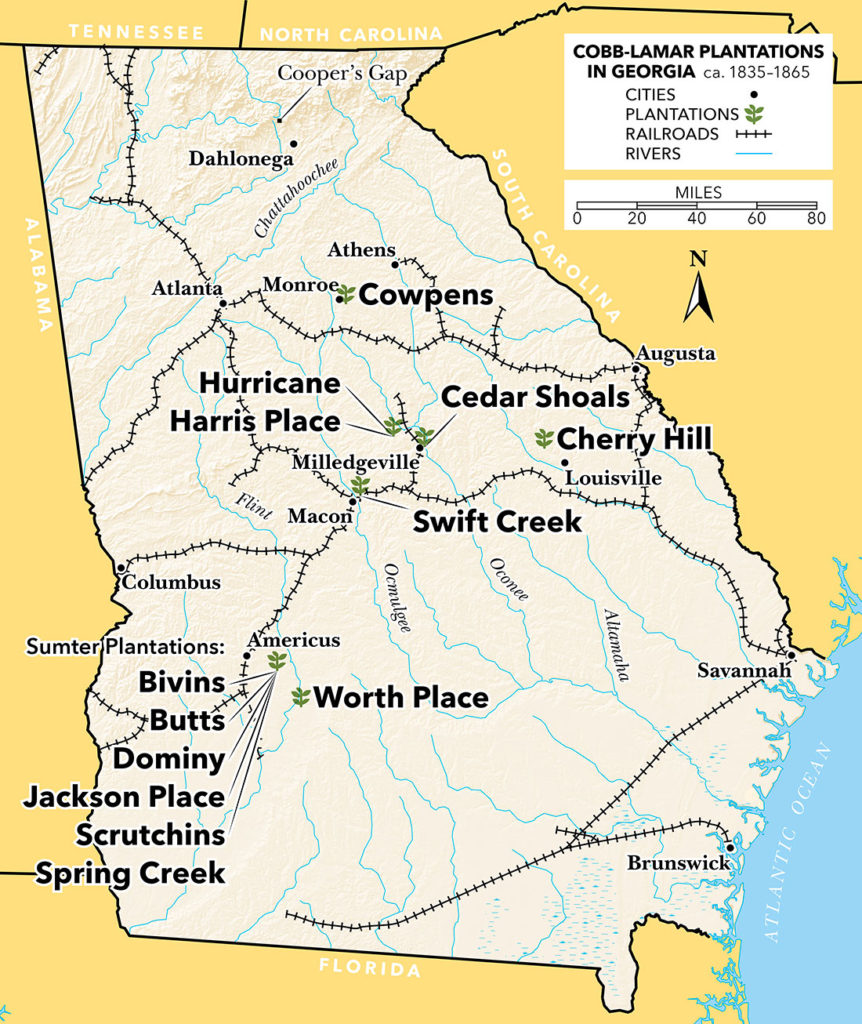

As a result of their merger, the Lamars and Cobbs owned 13 plantations in Georgia, including Cowpens, near Athens in Walton County. They developed a proto-chain-business-management system that made it possible for Mary Ann’s brother, John B. Lamar, to run all the plantations from his Macon mansion through the careful hiring and supervision of overseers, thus freeing Howell to throw his hefty energies into politics, taking him into the highest realms of the state, national and Confederate governments. At the heart of John’s management of the chain was constant communication by mail and by courier and the ability to move equipment, enslaved workers, food and supplies among the plantations as needed.

This book focuses on some of the enslaved people owned by that franchise, their constant maneuverings to keep their families together—or at least in touch—and their abilities to game the system by knowing how to approach their Lamar-Cobb owners to win approval for various schemes to bring family members back together or into better positions. The Lamars and the Cobbs believed strongly in the oxymoronic “humane” treatment of those they enslaved—except, of course, when they had to sell them to the highest bidder (and that episode was an aberration). Even so, if they needed a mother on one plantation and her son or daughter or husband on another, well, that was just business. And being on the plantation under the overseer rather than in the family mansions in Macon and Athens (yes, the Cobbs soon built another one) was a kind of banishment, even if they were in the house down there, rather than in the fields.

Even out in the shacks, though, families kept in touch through those who could write and through the drivers who brought supplies and also gave rides to enslaved visitors with vacation passes from one plantation or townhome to another. And on the plantation or in the big house, the enslaved, with no rights or power, still figured out how to resist demands that violated the unwritten rules of servitude—a revelation, along with that of the ways the enslaved could actually earn money, that illuminates a subject that has been buried in whitewashed stereotypes.

Several of the people who come alive in this book, such as Silva Carter and her daughter Aggy, were like members of the large Cobb family. Aggy, who grew up helping to look after the 12 Cobb children and became Mary Ann’s most trusted servant, was immediately repurchased by John B. and returned to his sister after that forced sale.

Nevertheless, “That experience shaped all the decades of her life. It taught her that she alone must shoulder the burden of protecting those she cared about most. Their safety required her to employ the few tools she possessed to convince Mary Ann, through countless daily interactions, that she and her family were loyal, dedicated and completely irreplaceable. Her success at meeting this challenge carried first her father and brother and then Isaac, Louisa and Fanny [her husband and daughters] over the rocky shoals of slavery and eventually into the safe harbor of emancipation. Half a century after the auctioneer’s hammer fell, a few blocks from where it began, Aggy Carter Mills died in a house all her own, a wife, a grandmother and a free woman.” Others were not so fortunate.

The authors—Christopher R. Lawton, Laura E. Nelson and Randy L. Reid—are what you might call “citizen historians,” in the sense that though they are academically trained, they’re not college professors publishing to avoid perishing. Seen/Unseen has an immediacy and a freshness that makes compelling reading, and in addition to the bountiful excerpts from the correspondence, there are pictures, facsimiles of documents, helpful genealogical charts and a couple of spiffy maps by Flagpole Production Director Larry Tenner.

Most importantly about this past: “It’s not even past,” as Faulkner once wrote. There are a lot of people walking around Athens and Georgia right now who are descended from Lamar-Cobb ownership and enslavement that still affect their lives and ours.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.