In commemoration of Black History Month, the team members of Reconstructing Black Athens have been exploring the legacies of slavery, segregation and racial inequality in Athens. This week, in our final article, we turn our attention to a historic problem still haunting us today: infant mortality.

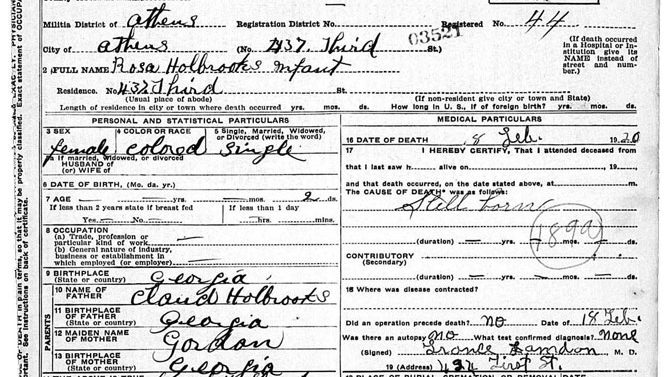

On Feb. 6, 1920, Rosa Holbrooks’ infant was born in Athens. Two days later, the child died. She never had a name. The death certificate simply listed the cause of death as “still born.” Mack and Payne Funeral Home handled the burial. At one point, a small, dollar-bill sized glass or metal placard probably marked her grave. But nothing remains. She has no tombstone or marker of any kind. The precise location of her gravesite has been lost to time.

Over the course of its 121-year history, approximately 3,500 African Americans were buried in Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. Many are like Rosa Holbrooks’ infant: They don’t have a marker, and we don’t know the locations of their graves.

Most, however, had a funeral. In the South, African-American funerals typically commenced by cleaning and laying out the departed. It was a family and a community affair. According to historian Lynn Rainville, the wake, or funeral, often held at the home of the deceased, “provided an opportunity for socializing and feasting, often with culturally specific foods.”

At times, there was a striking contrast between the poverty experienced by the deceased in life and the opulence experienced in death, as black families poured their resources into providing a handsome hearse, a well-made coffin and abundant floral arrangements.

“In the African-American community,” Rainville notes, “the funeral may have provided a chance to confer on the deceased a social dignity that was often lacking in life.”

Then came the burial. The Holbrooks family presumably followed such customs after losing their infant in 1920. Having most likely cleaned and dressed the infant, Claude Holbrooks and his wife Rose most likely held a public or private gathering at their home on Third Street before laying their infant to rest at Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery.

Crammed between an advertisement for “Lorraine seersucker suits” and a society notice announcing “The Perfect Flapper,” a small article appeared on page seven of the July 27, 1924 edition of the Banner-Herald: “Athens Is Third in Infant Deaths.” In 1923, Athens had the third lowest infant mortality rate in Georgia. Savannah had the highest: 136 out of 1,000 infants died before reaching their first birthday. While comparatively lower than some cities, infant mortality in Athens was still far too high, especially in the African-American community. In Athens, 8.4% of all children died prematurely, as witnessed in the death visited on the Holbrooks.

Children were dying at an alarming rate in Athens. Children are still dying at an alarming rate in America. “Infant mortality is a surrogate measure of how well a society ensures the health of its people, particularly its women and children,” notes the Georgia Department of Public Health. Between 2007–2011, the state’s infant mortality rate was 7.3 deaths per 1000 births; 5,175 infants died in that five-year time span. Maternal mortality was worse still; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2016.

The United States is not ensuring the health of citizens equally. Rather, they are dying unequal deaths in America. CDC statistics only serve to underscore this alarming epidemic. Among African Americans, infant mortality was 11.4 deaths per 100,000 births in 2016, and maternal mortality was 42.4 deaths per 100,000 live births between 2011–2016. For white mothers and their children in the same period, however, the CDC reported only 13.0 deaths per 100,000 live births for white, non-Hispanic women and an infant mortality rate of 4.9. Sadly, then, the death of Rosa Holbrooks’ infant a century ago was not exceptional. Such a thing is still not atypical in Georgia. The death of African-American infants or mothers has been normalized in America.

The members of UGA’s Department of History are researching the lives and deaths of Athenians buried in Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. Using Athens-Clarke County death certificates, mortality censuses, mortuary records and coroners’ inquests, the project reveals serious disparities in life expectancy and health outcomes based upon race. While this is still a work in progress, we invite those interested to visit our webpage at ehistory.org/adp.

If you are aware of other records that would help us reconstitute the story of life and death in Athens, especially as variously experienced by blacks and whites, please contact Tracy Barnett: [email protected].

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.