Once upon a time, we lived in a pre-COVID world. It was a much less stressful world—without masks, testing, social distancing or monitoring new cases, hospitalizations and deaths. As we enter our third pandemic summer, you could easily think that we were in pre-pandemic times again.

Much of the American public is, understandably, exhausted. According to a May 2022 Pew Survey, “just 19% of Americans rate the coronavirus outbreak as a very big problem for the country, the lowest share out of 12 issues included in the survey. In June 2020, in the early stages of the outbreak, 58% rated it as a very big problem, placing it among the top concerns at the time.” The largest concern in the survey: inflation.

The public sentiment on the pandemic has been fueled by unclear messaging, data and policies from once-trusted public health institutions like the CDC, but part of the complacency can also be attributed to the economy, as many Americans can no longer afford to take days off of work to isolate. Just because we are tired of dealing with the pandemic or pretend the pandemic is no longer happening doesn’t mean that it’s not still with us. In recent weeks, there is more and more evidence to suggest we’ve been living in a fairy tale as a country. This pandemic is not over, even if we have decided that we are done with it.

In the last two months, new cases of COVID-19 in Georgia have more than quadrupled. In Athens, the seven-day running average of new cases was up to 17.7 per day as of May 25, from a low of 1.1 on Mar. 25. So far, at least 222 Clarke County residents have died from COVID-19, including one last week. While hospitalizations have not risen to alarming rates, nine Clarke County residents were hospitalized for the virus last week. In total, 1,224 residents have been hospitalized to date.

Hospitalizations and deaths are lagging indicators, so having a means to monitor rising viral levels in the community before it affects our health-care system locally is just as important now as in other phases of the pandemic. Sadly, the rise in cases across the country has been difficult to monitor and see in the data for a number of reasons, which has contributed to the general lack of concern among the public.

The rising prevalence of at-home tests has meant that many people stopped seeking out PCR testing that is reported to the Georgia Department of Public Health. While at-home testing is another tool for the public to self-monitor, these test results are not recorded in the official statistics. In fact, there is no mechanism for reporting these tests, according to DPH Communications Director Nancy Nydam. While some may continue to seek out traditional PCR testing, any increase in positive case counts in CDC or DPH data is a vast undercount.

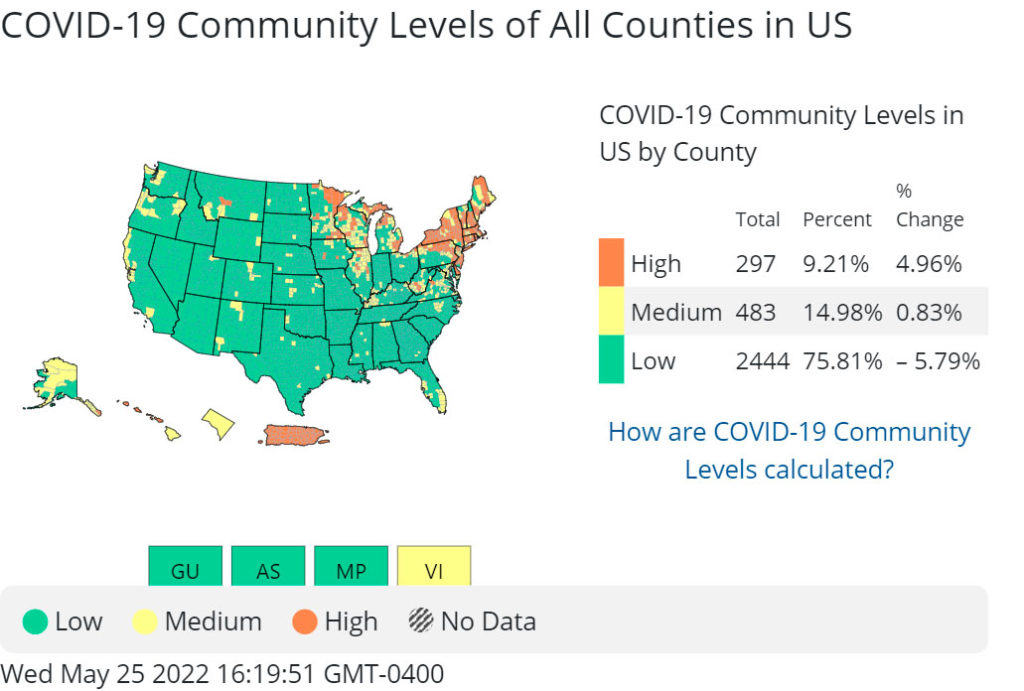

Just after the height of the Omicron wave, the CDC announced that it would take a different approach to monitoring the pandemic that would focus less on new case numbers and more on the well-being of hospitals in local communities. While the move made sense to many public health experts initially, it became apparent fairly quickly that the “Community Levels” map and color-coded scale that was created for this new monitoring phase was flawed.

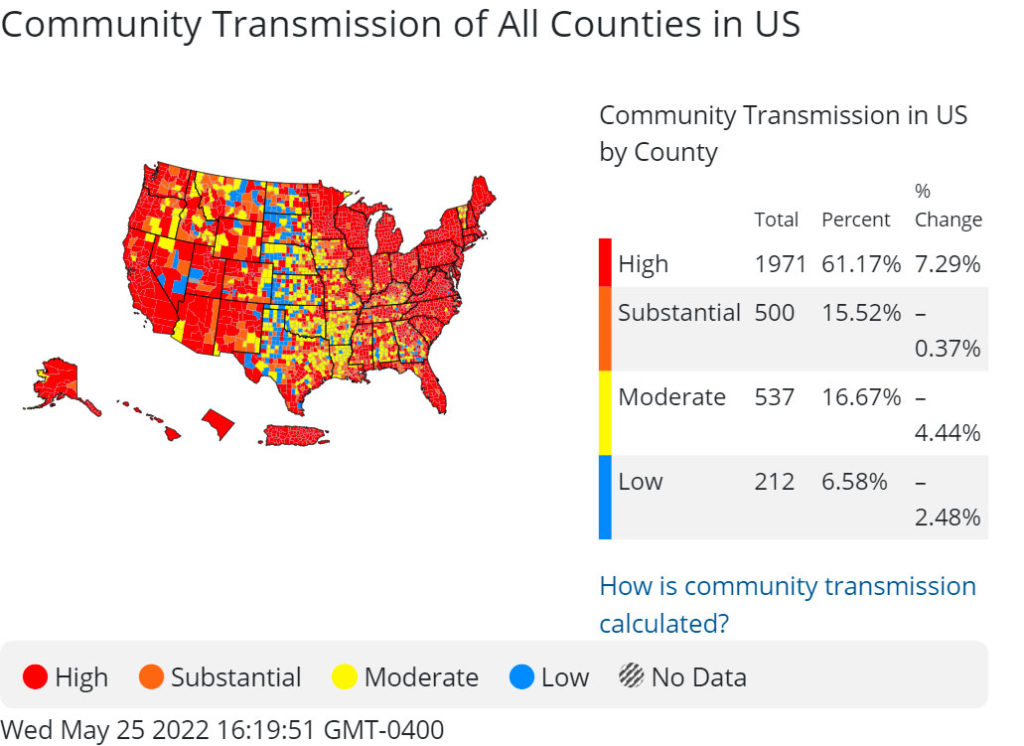

Up until just a few weeks ago, this map—which included green, orange and yellow—showed that 90% of the country was in a low- or medium-transmission community. On the other hand, the “Community Transmission” map—which is what the CDC had been using to monitor conditions since the beginning of the pandemic—showed a much different picture of viral spread. With a color scale of red, orange, yellow and blue, a timelapse of the last few weeks showed a country that is becoming more and more red and orange, with far more viral spread than most were aware of. According to this map, Clarke County and many of the surrounding counties are bright red right now, indicating high levels of viral spread.

Last week, the CDC changed the “Community Levels” map key, in part because of severe criticism by public health experts. A week after saying most of the country was safe, CDC Director Michelle Walensky tweeted that 32% of the U.S. population was in a medium- or high-risk community. That rate has only increased for much of the country.

The admission chips away at the attitude that everything is fine, according to microbiologist Amber Schmidtke, who writes about the pandemic in Georgia. “The current U.S. COVID-19 strategy is to feed Americans into the disease chipper,” Schmidtke wrote in a recent newsletter. “There are no brakes on COVID-19 at this time. Transmission is happening, unimpeded.”

To complicate matters further in Georgia, DPH moved to weekly COVID-19 updates at the end of April. With less robust data to report because of at-home testing, the move seemed inevitable, but it has meant less ability to keep an eye on community transmission levels on a day-to-day basis. Given that we are now in at the start of another surge—albeit one that most people seem to be unaware of—even less robust data on new cases might have been useful.

Wastewater monitoring is the one tool that gives us a clear indication of viral levels in a community, gives complete anonymity and is easily supported by the already existing wastewater treatment facilities across the country. DPH says they are working on getting more wastewater monitoring up and running across the state, but so far that effort has been slow going.

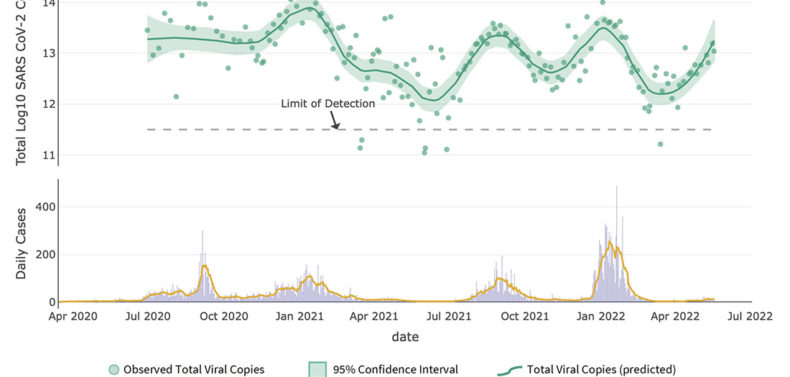

In Athens, professor Erin Lipp at the UGA Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases has been monitoring Clarke County wastewater. Over the course of the past five weeks, wastewater monitoring from Lipp’s lab has shown a steady but persistent increase in viral levels. The most recent update showed that viral loads were back to levels not seen since February, even though, due to limited clinical testing, the seven-day running average was much lower than the tail end of Omicron.

While wastewater monitoring is a useful tool, the future of the pandemic monitoring in Clarke County could be at risk. Funding has not been secured for continued monitoring past the beginning of the fall semester, Lipp said. With UGA’s recent announcement that COVID-19 data and safety protocols will no longer be enforced, alongside lack of official data, the loss of this tool for the community could have a severe impact in our ability to know what is happening with the virus.

Protecting Yourself

For much of the public, the risk of spreading COVID-19 is no longer a concern. Many people just don’t see it as a real public health threat at this point, but that is short sighted, said cardiologist Jayne Morgan, executive director of the Piedmont Healthcare COVID-19 Task Force. “The pandemic isn’t over,” she said. “Equating and minimizing and marginalizing the pandemic as a virus similar to the flu is disingenuous.”

At this point, we do have tools that we did not have at other points in the pandemic. Therapeutics can help curtail a severe infection for those who are most vulnerable. Vaccines, which may not prevent infection altogether, do provide a level of protection against severe disease that might result in hospitalization. Booster doses provide extra protection.

On the other hand, COVID-19 spread has fueled continued mutations over time. These new variants are becoming increasingly more capable of evading immunity. As more variants pop up, it’s likely that we’ll see less protection from booster doses and the vaccine.

We could see a large rise in new cases this summer that don’t cause large numbers of hospitalizations or deaths, said Morgan, but allowing COVID-19 to spread and mutate further may create a more dangerous and virulent variant this winter. As it stands, several Omicron sub-variants are mutating and taking hold simultaneously. “The virus is evolving in a much more consequential way,” Morgan said. “We need to rethink our public health strategy. This Omicron variant has spun off at an alarming pace.”

Repeated infections have been shown to increase the chances of developing chronic health problems associated with “long COVID.” While research on long COVID is still at its infancy, at this point the data indicates that repeated COVID-19 infection can produce chronic problems such as memory loss, cardiovascular problems and prolonged exhaustion, according to Morgan. “Our complacency could come back to bite us,” she said.

While many have let down their guard at this point in the pandemic, there is a lot we can do as individuals to help combat the spread of the virus. The spread of this virus depends on human behavior, said Morgan.

Credible Sources: In Athens, the CEID wastewater lab data is updated each Friday afternoon. DPH updates, released weekly on Wednesdays now, provide some gauge of viral spread. The CDC Community Transmission Map provides the most clear gauge of community spread, but the newer Community Levels map does not give an accurate representation of viral spread. Knowing where things stand locally can help you make your own risk-based decisions about socializing, masking and just generally being more vigilant in your own use of public health measures.

Testing: Through the U.S. Postal Service, each household is now eligible for eight free at-home antigen tests. Further, if you’ve not taken advantage of at-home tests in recent months, you’re eligible for another eight free tests. Stock up now so you’ll have plenty on hand if the need arises in the future.

If you test positive, DPH recommends contacting your health-care provider to receive appropriate medical care, especially if your symptoms get worse or you are an older adult or have an underlying medical condition. There are therapeutics that can help fight off severe infection in the first days of symptoms. DPH also recommends staying home for five days, isolating from others in your home, communicating with close contacts and wearing a well-fitted mask when around others.

Get Vaccinated: Finish your two-dose vaccination, if you’ve only had one dose. Get a booster, if you haven’t already.

Be Aware of Patterns: If you look at the patterns of surges for Athens, you can see when we have had surges in the past. This can help inform your own behavior and know when you might want to wear a mask or avoid crowds or move events and social activities outdoors. Further, if you’re aware of these patterns alongside monitoring current viral levels, you can carefully time your booster doses. Booster doses provide a level of extra protection for about four months. If you can see that a surge is coming, a booster dose ahead of the surge is a smart decision, especially for more vulnerable populations.

While the pandemic is still at our doorstep, we all have the ability to do individual risk assessment based on our own health and age, consideration of close family members and friends, and the well-being of others in our community. At this point, most public health proponents continue to offer the same advice—use the resources and tools available to assess your own risk and make informed decisions about what precautions or measures you need to follow. “It all comes down to the human behavior and the decisions we make now,” said Morgan.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.