It’s been a little over three years now since the threat of COVID-19 abruptly halted life as we knew it in Athens. Seemingly all at once, in March 2020, UGA suspended in-person classes, events were canceled in rapid succession and the Athens community became an eerily quiet landscape as residents sheltered in place after scrambling to find toilet paper, soap, cleaning products and hand sanitizer. We adapted to the challenge of working and learning from home, and found new ways to bide our time as we waited for the nightmare to recede.

It didn’t happen all at once, but in the three years since then, we have adapted and adjusted, learning to understand data and assess our own risk of infection. While life is back to a more normal day-to-day now, the pandemic left considerable scars on our community, particularly our health and well-being, in a variety of ways that will require a shift in policy and funding to repair for years to come.

COVID Is Still a Threat

After three years of relentless updates on COVID-19 cases and data, it’s easy to glaze over the numbers now without consideration for the panned-out impact and larger context of the pandemic for our community. To date, there have been 31,007 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Clarke County, according to Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH) data. That number doesn’t include positive antigen at-home tests or UGA students who aren’t counted in the data as residents, and is likely a vast undercount of just how many residents have been infected in the last three years. DPH numbers also show that nearly 1,800 residents have been hospitalized from the virus, as of Mar. 22, and 247 Athenians have died from COVID-19.

In this third year of the pandemic, the community here and many nationwide have become considerably more complacent—and understandably so thanks to cultural, political and economic pressures and policy changes—in efforts to test, getting vaccinated and boosted and practicing recommended public health measures like mask wearing. People have come to accept a certain amount of risk to get back to a more normal way of life. So what does that risk look like for the past year?

From Mar. 11, 2022 to Mar. 15, 2023, there were nearly 5,000 new confirmed cases and roughly 900 new positive antigen cases, according to DPH. For the previous year, the data showed more than three times as many cases. However, health experts don’t recommend using case numbers to judge the state of the pandemic. Hospitalizations and deaths provide a better gauge, according to public health expert Amber Schmidtke. Yearly data for Clarke County showed 88 deaths in March 2021–22, and 38 in March 2022–23. Hospitalizations have been consistent, with 660 in the past year and 655 the year prior.

For a significant portion of the population, the pandemic continues to be a very serious concern. Mainly, those who are immunocompromised or have other health concerns are still very much at risk. For this group, which the CDC estimates as 3% of the population nationwide, any infection, even the less lethal variants we saw last winter, are still a very real life-and-death risk. According to a recent CDC study of 22,000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 12.2% were immunocompromised.

Health Care Disparities Widen

Many of these problem areas in our health-care landscape were already present but were exacerbated by the pandemic.

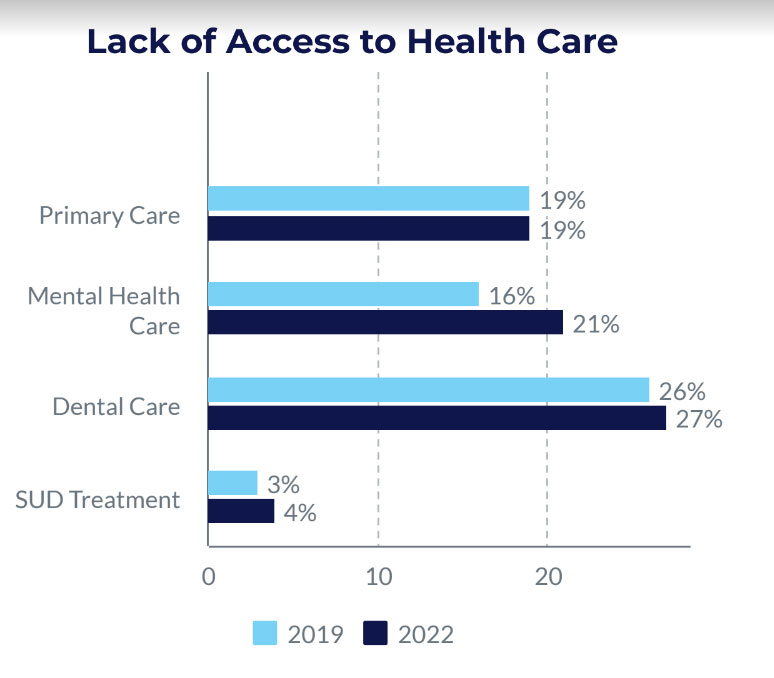

Clarke County has high levels of poverty and need and significant wealth and resources, according to the latest Athens Wellbeing Project survey by Grace Bagwell Adams of the UGA College of Public Health, and health care has become more difficult to access. The third iteration of the survey found that “systematic disparity cuts across all domains of life for low income families, racial and ethnic minorities, and those with a high school education or less.” This disparity falls disproportionately on children and older adults.

Gaining access to healthcare has become consistently more difficult due to a decline in health insurance coverage for older adults and low-income families in Athens, survey data from 2016, 2019 and 2022 shows. In the last seven years, health insurance coverage has declined significantly in Athens, with 22% of households lacking coverage in the most recent survey, compared to 19% in 2019 and 13% in 2016. Even with health insurance, 23% of Athenians said they had been turned away by a provider because their type of insurance was not accepted. For low-income families, this statistic increased to 30%.

The data in the latest survey shows that there are not enough providers, particularly for mental health care and dental care, and for primary care for low-income patients. This problem, according to recent data compiled by the Kaiser Family Foundation, is not unique to our county, which is designated as a Health Professional Shortage Area. Statewide, only 40% of primary care needs are being met, and about a third of Georgians live in an area with a primary care shortage. Only three counties in Georgia meet the standards for sufficient primary care for the population.

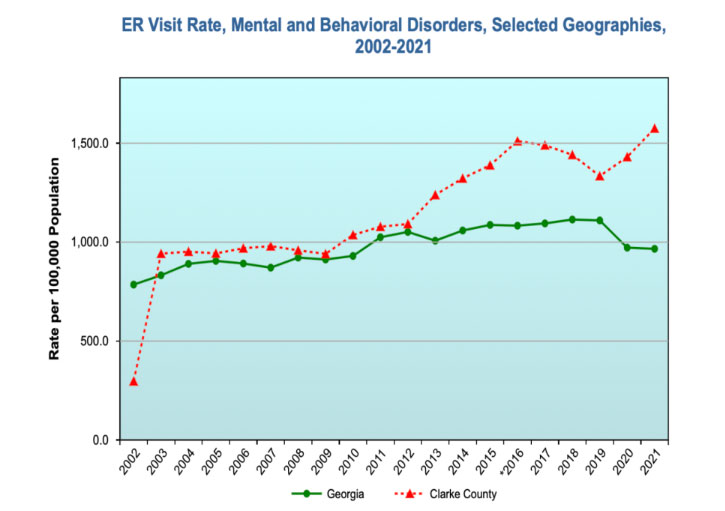

Behavioral health is another problem area for Clarke County and the state as a whole. According to the survey, 49% of respondents had lost a close friend or family member in the last two years. Of those who experienced a death of a loved one, 41% reported that the death was the result of COVID-19. With the social isolation and grief that many experienced during the pandemic, the demand for mental health care has risen while access and a shortage of providers in the area continues. Overdoses and substance abuse have become more prevalent, with drug overdose ER visit rates rising from 220 per 100,000 people in Clarke County in 2019 to 280 per 100,000 in 2021.

The data also shows that health-care providers experienced significant challenges in Athens, including fatigue, work related stress and burnout. Statewide, this has led to a loss of health-care workers. The Georgia Healthcare Workforce Commission report, released in December 2022, shows that, because the need for health-care workers is projected to increase consistently in the coming years as baby boomers age, there’s a great need to educate and retain health-care professionals to replace those lost to burnout caused by the stress of the pandemic years.

Slow Progress on Solutions

Potential solutions and policy proposals aim to curb some of the problems that ail Athens and Georgia, but progress has been slow. The impact of loss of the COVID-related Medicaid expansion, which will begin phasing out in April, suggests more difficulties for low-income Athenians are ahead, with nearly half a million people potentially losing coverage statewide.

Instead of accepting federal funding to expand Medicaid under the Obama-era Affordable Care Act, Gov. Brian Kemp is implementing his “Pathways to Coverage” program, which would cover 100,000 Georgians in its first year of implementation and cost the state around $249 million, or roughly $2,490 per new enrollee. In contrast, the first year of implementation with full Medicaid expansion would cost the state about $239 million and cover nearly 500,000 Georgia for just $496 per new enrollee. The federal funds with full expansion, notes the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, would more than offset the state costs of expansion for at least the first two years.

At least one of the Georgia’s Healthcare Workforce Commission’s recommendations gained some traction this year. The commission’s recommendations included three basic areas and solutions, including maximizing the existing workforce, optimizing the health-care education system and attracting new workers. House Bill 383, the Safe Hospitals Act, passed the House and gained approval from the Senate Committee on Health and Human Services last week. It’s meant to help curb violence towards health-care workers, which spiked significantly in the contentious political environment of the pandemic and is cited as a major reason for leaving the medical profession.

“COVID has been extremely challenging for health-care teams here and all over the world. Challenges have ranged from supply shortages, to surges that in some places overwhelmed the healthcare system, to high burnout rates of physicians, nurses and other staff,” said St. Mary’s Healthcare System Public Relations Manager Mark Ralston. “We are immensely grateful for the support our communities have given us during times of especially high stress. We are most grateful for the commitment, dedication, self-sacrifice and compassion our staff and providers have demonstrated throughout the pandemic.

“We are encouraged to see Georgia and other states expanding opportunities in health care education to address critical workforce shortages caused by the pandemic and other stressors,” Ralston added. “And we encourage everyone to remember that COVID is here to stay, just like other serious viral diseases, and that vaccination and staying home when sick remain the best way to protect ourselves, our families and our communities.”

Schmidtke echoed Ralston’s sentiments on the lingering COVID-19 pandemic. “I wouldn’t say that the pandemic is over,” she said in her final newsletter. “And my heart goes out to those who are immunocompromised and having to navigate a treacherous disease landscape. As the public health emergency lifts, I think we will see disparities in health that are already too familiar in this country. We must do more to make sure that those who have been medically underserved continue to have access to health education, routine and preventive care, robust availability of nutritious food, mental health, vaccines and other tools that are important in preserving both quantity and quality of life.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.