Last week, reporters from the Indianapolis Star filed a state public records request and learned that while Mike Pence was governor he communicated using a hackable AOL account to conduct state business. And reporters used the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) law in 2015 to show that Hillary Clinton used a private email server during her tenure as Secretary of State—a revelation that did as much as anything else to cost her the presidency.

Now, in the early stages of an administration that regularly deploys falsehoods and unsupported claims, John Moss, the man who made those earlier revelations possible, may just be the most important Trump-slayer you’ve never heard of. Moss was a 13 term Democratic congressman from California’s Central Valley and he spent half of his legislative career doggedly trying to pass a single piece of legislation: The 1966 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

I’ve filed 158 FOIA requests for Democracy in Crisis since Trump took office. Moss’ FOIA legislation may end up being Democracy in Crisis’ most effective weapon in getting truthful information from the Trump administration. So far, we’ve asked government agencies to turn over everything from emails about election day, drafts and memos related to the DREAM Act and the travel ban, and records about the Trump transition team. Without Moss’ steadfastness and single-minded commitment to open government, these Trump administration records would remain trapped in government agencies (and they may still be stalled nearly indefinitely). Moss was brash, blunt, and indifferent to partisanship when it came to his insistence on open government, even when he had to step on toes of his fellow Congressman to push his transparency agenda. Moss despised schmoozing in a town full of schmoozers.

In an interview with Michael Lemov, chief counsel to Moss’ committee from 1970-1978 and author of “People’s Warrior: John Moss and the Fight for Freedom of Information and Consumer Rights,” Lemov says that Moss believed “it is the peoples’ right to have their records. The public records are the peoples’ records. Period.” Moss wrote the FOIA law to ensure that journalists and, perhaps more importantly, “all persons,” have the right to access federal government records.

Moss’ interest in open government was first piqued in 1954 when 2,800 civil servants were fired for “security reasons” and the Civil Service Commission refused to turn over records about the employees when Moss requested them. Moss suspected that the civil servants were fired over suspected disloyalty during a time of rampant Cold War era fear mongering. Lemov recalls, “it was his first brush with government secrecy, and he didn’t forget it.” Moss saw that federal agencies “don’t like sunlight” and that the FOIA law could become the needed antidote to allow the American people to know what their government is really up to.

As chair of the obscure Government Information Subcommittee, Moss was regularly stonewalled by federal agencies when he requested information. He recognized that agencies were over classifying documents as “secret” and “confidential”, thus making the federal government opaque and unable to be held to account. Until passage of FOIA, the default position of the government was, according to Lemov, “when in doubt, classify.”

Years after FOIA passed, the Sacramento Bee filed a FOIA request to the Department of Justice for records about Moss and the request produced folders full of FBI surveillance including the March 31, 1960 FBI agent note: “Our relations have not been favorable with Congressman Moss.” Presumably, Moss fell out of favor with the FBI because of his relentless demands for FOIA. More than 30 federal agencies and members of both parties who testified against passage of FOIA and many of Moss’ colleagues urged him to back down from the bill.

In 1965 Moss’ found an odd bedfellow as a FOIA champion in a freshman Republican congressman, Donald Rumsfeld, who later became secretary of defense and an architect of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Rummy and a cohort of Republican congressman planned to use the FOIA law to embarrass Democrats. The Democrats ultimately called Rumsfeld’s bluff, and FOIA was begrudgingly passed by Congress. Decades later, it would be reporters’ use of the FOIA law that would expose Rumsfeld’s role in approving the atrocities and torture at Abu Ghraib prison.

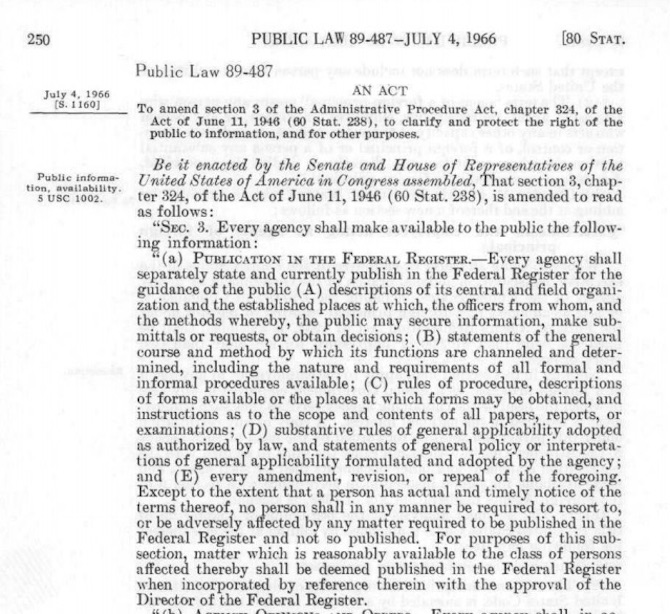

Lemov recounts that despite signing FOIA into law on July 4, 1966, President Johnson was so opposed to the legislation he told his aide Bill Moyers, “I thought Moss was one of our boys, but the Justice Department tells me his goddamn bill will screw the Johnson Administration.”

The FOIA law only applies to records held by the executive branch of the federal government. Congress and the courts are exempt from FOIA record requests. The legislation proved to be the necessary catalyst for states and cities to pass public record access laws of their own. Currently, every state has its own version of a FOIA law that allows for requests of state records.

In reflecting on the value of FOIA, Kansas City Star reporter Mike McGraw said, “Because of John Moss, going to my mailbox can be like Christmas morning. If I get a huge package from the government, I rip out the documents looking for clues about how my government works and—when it doesn’t—why it doesn’t. I constantly urge journalists to use the Freedom of Information Act, and use it often so we can keep the bureaucrats used to the idea that these records are ours—not theirs.”

Moss’ FOIA legislation and its subsequent adaptations are far from perfect. The law is filled with exemptions, such as the government’s right to withhold records related to national security and personal privacy. Yet a saving grace of the FOIA law is that the burden of proof for such exemptions is on the government, rather than the individual requesting the records; meaning if Democracy in Crisis is told by the Justice Department that records are being withheld for national security reasons and we take the Department to court, the DOJ will have to prove to a judge that the records should indeed be kept secret.

“Are we better off now than we were? Of course. Are we where we should be? No, by no means,” Moss told Lemov.

“What we did was just a start. But there was nothing monumental that I wanted to do that I did not do. I didn’t back away from many challenges. Sometimes you cannot compromise, you have to fight.”

When I asked Lemov what Moss may have felt about the Trump administration, he replied, “In a word? Disappointed.”

Moss, who died in 1997, equated government opacity with the origins of totalitarianism. In 1956 he said, “The present trend toward government secrecy could end in a dictatorship. The more information there is made available, the greater will be the nation’s security.”

The Washington Post recently added the phrase “Democracy Dies in Darkness” to its banner. Rep. Moss’ battle to bring FOIA legislation to life may just end up being the most valuable tool we have in keeping away the darkness during the Trump administration.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.