Long before Athens existed as we know it today, the land located between the forks of the Oconee Rivers was known as Ikunu-tchaka, or Beloved Land, by the Creek (Muscogee) Indians. David Hale, whose reverence for the natural world has always been observable through his art—which extends beyond his widely admired illustrations, tattoos and murals—dedicates his latest body of work to the flora and fauna that inhabit this land. Created over a year and encompassing over 100 original works, his exhibition “Beloved Land” varies among drawings, paintings, etchings, assemblages and interesting wooden constructions. From deer, birds and foxes to snakes, bats and frogs, all creatures great and small are rendered with a sense of sacredness.

The Lyndon House Arts Center will host a reception celebrating its summer exhibitions on Thursday, June 15 from 6–8 p.m. In addition to “Beloved Land,” the lineup includes “To & Fro: Correspondence Art by Jack Logan and Kosmo Vinyl,” a collection of original pop-culture themed postcards; “Time Warp… and Weft,” woven works by Janet Austin, Geri Forkner, Janette Meetze, Rebecca Mezoff, Tommye Scanlin and Kathy Spoering; and “In Wood and Word: Bible Scenes Carved by Cal Logue.”

Flagpole: How were you first introduced to the history and culture of the Creek Indians?

David Hale: I have been interested in American Indian history and culture since I was a child exploring around the woods near my home in Marietta, and at various sites like the Etowah Indian Mounds. A few years ago, I met Steven Scurry and saw a lecture of his on the Oconee Wars, and actually read his articles in Flagpole. That opened my eyes to a much greater depth of the story, and I have pursued it since. I also have found things like pottery remnants and arrowheads on the land that I live upon, and that has deepened that connection and story.

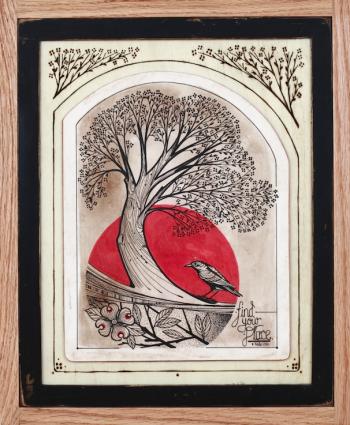

“Find Your Place” by David Hale

FP: What lessons do you think people today can learn from this area’s ancestors?

DH: I think people should be aware that connection to ancestors is a relationship, and it is important not only to recognize what can be received, but what can be given. This, to me, is a very real and tangible relationship, and one that should be recognized by individuals and the larger community if we are to adopt a holistic and healthy manner of existing in this place. This is a land of displacement, and in one way or another you are consuming the stories both told and untold by the ancestors of this place.

This is not only one cultural group; this can also be seen with what is currently happening at Baldwin Hall. Everyone and everything is woven into this story. As the living, we act as a bridge of communication. You can imagine it as the ancestors above and the earth below; there must be a conduit between these two, and we are that conduit. All in all, we can start by taking the time to say “thank you” daily to those that came before us.

FP: In what ways do you find that the ancestors’ connection to the land resonates with your own?

DH: I know with my intuition and the compass that is my heart, that others before me have loved this land in the way that I love it now, have walked this land in the way I walk it now. I also know that my connection is dependent on this web that is woven together with them. I am humbled daily by what this place offers me and my family, and I know that when I drink the water and eat the food of this land I am very much consuming the flesh and blood of those who lived and died on this “beloved land.”

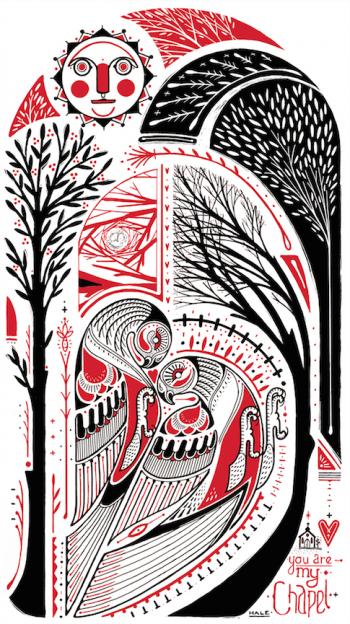

“You Are My Chapel” by David Hale

FP: Can you tell me about your process for creating “Beloved Land”?

DH: About a year and a half ago, I set the intention for making this body of work. The process was initially anchored in creating images inspired by things I saw and experienced on the watersheds of the forks of the Oconee River. I began collecting ideas and experiences with my family and translating them into drawings that would also be translated into tattoos as well.

There was a structure of around 10 images a month at first, but as the project continued it began to read much more like the Oconee itself. The river maintains a general course but is also fluctuating in its nature, and the process of the show was much like this, and difficult to contain in words. All this story is left in the images, and hopefully the process can be found there for dedicated viewers. I will say, there is an abundance of inspiration around us that draws from a bottomless well of creation; I am just the guy pulling on the rope.

FP: Do you consider traditional artwork or craftsmanship of any specific Native American tribes to be an influence? The “Love Hawk Bird,” for example, calls to mind the Pacific Northwest, both in style and color palette.

DH: I try to be sensitive to cultural appropriation in my work, while also allowing myself to explore naturally my inherent sources of inspiration. I don’t start a piece of art trying to make it in the “style” or “technique” of one particular people or person; the art-making process is very intuitive and experiential for me, and I could hardly claim to have that kind of control over it.

As for American Indian influences in my work, I have been so deeply inspired since childhood by the art created on this continent as a whole, both by American Indian peoples and all others who have been blessed enough to grace this land. I have been welcomed into so many homes. It’s incredibly difficult for me to draw a line in the sand between groups of people and their art, when I have seen the sand shifting for so many generations. I see a lot more similarities than differences, that is for sure!

One amazing thing about the displacement that has occurred on this land is that we are in a period akin to post-floodwater ecological stage, where so much fertile soil and seed varieties have spread. I hope my art shows some of the incredible gratitude for all these peoples, and not just the things they have created, but from where they have sourced these creations.

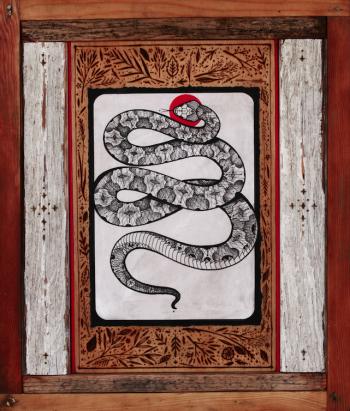

“Copperhead” by David Hale

FP: What was the experience of creating “Beloved Land” like for you personally? Did it strengthen or alter your understanding of the natural world, or mankind’s role within it?

DH: If I were to try to find a common thread in the process… it is a deepening sense of humility and gratitude. It is humbling to find out how little I have to do with the process of creating this art, and I have found that deeply and completely in creating this body of work. I am an instrument, not the musician or the maker. I truly am the smallest component in this act of making, and it becomes a visceral experience to begin to witness that truth.

Humankind is of nature, and there is not a division between the two; our role is inherent in this story. This land does not recognize our accolades, and our egos merely add unnecessary weight to our footfalls on this place that supports us so fully. I hope I learned to live a little more like this place, not just for myself, but for my family, our ancestors and the generations to come—giving more completely and expecting less in return.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.