A local entrepreneur and University of Georgia English teacher who writes under the pen name Dr. Billy Currell has recently self-published his first book, Kentucky Fried Tender, a uniquely-structured tour de force that argues to establish, over a staggering thematic and historical scope, the three pillars of humankind as he sees them: Chicken, Women and Money. Tender, Tender and Tender, or, more specifically, that chicken fried by the benevolent Colonel Harland D. Sanders, that money generated by the selling of said chicken, and those women wowed-to-swooning by bucketfuls of its greasy supple essence.

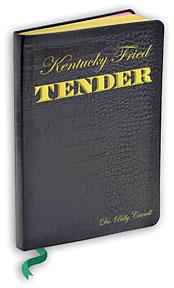

The author, the real-life son of a preacherman, didn’t spare any expense on the appearance of his first book; he pimped it out, bound it in leather with gold-embossed script and one of those spine-embedded cheesecloth bookmarks. The aesthetic decision attests not only to the severity of his vision – it looks like the Holy Bible, which shows you how high he’s aiming – but also suggests Currell’s business acumen. He knows that, just as the Colonel’s late-life riches serve as no small tribute to his iconic bucket and the biological success of his beloved peacock depends on its striking 10-eyed train, his own literary debut must look distinctive in order to make a mark in this era where the electronic forms of media are threatening to make mere artifacts out of books. Currell realizes, of course, that if he is going to survive to see another business day, his product must sell. As far as the brutal laws of commerce go, the book itself is evidence that the author knows of what he speaks, and what we as a buying public have as a result is a fascinating bit of DIY ingenuity that falls somewhere between folk and pop art.

The author, the real-life son of a preacherman, didn’t spare any expense on the appearance of his first book; he pimped it out, bound it in leather with gold-embossed script and one of those spine-embedded cheesecloth bookmarks. The aesthetic decision attests not only to the severity of his vision – it looks like the Holy Bible, which shows you how high he’s aiming – but also suggests Currell’s business acumen. He knows that, just as the Colonel’s late-life riches serve as no small tribute to his iconic bucket and the biological success of his beloved peacock depends on its striking 10-eyed train, his own literary debut must look distinctive in order to make a mark in this era where the electronic forms of media are threatening to make mere artifacts out of books. Currell realizes, of course, that if he is going to survive to see another business day, his product must sell. As far as the brutal laws of commerce go, the book itself is evidence that the author knows of what he speaks, and what we as a buying public have as a result is a fascinating bit of DIY ingenuity that falls somewhere between folk and pop art.

On a literary level, the secret to this book’s success lies in its various mixtures; like the blend of 11 herbs and spices that the Colonel lovingly infuses into his nourishing milk and egg bird-batter, Dr. Currell adeptly combines ostensibly contradictory disciplines and attitudes to create an entertaining, informative and engrossing read. A keen awareness of Darwinian theory flavors a deep and lived-in knowledge of the Bible. Intel Founder and technology philosopher Gordon Moore trades recipes with some hack biographer of Colonel Sanders, name of John Pearce. A chapter detailing the too-sober doom-and-gloomery of Thomas Malthus and Paul Ehrlich presages a piece of fiction that, with a little fleshing out, could one day find itself in “Penthouse Forum.”

Currell chops his chapters into brief vignettes that rarely exceed a page in length; however, an overview of the book reveals a strong thematic unity, and its schematic structure is tracked obsessively by an exhaustive index and a footnotes section whose relationship with the conceits made within the text are always valid, and often hilarious. An impressive understanding of human neurological function and evolution, the developmental principals of world capitalism, and American political history, among other huge concepts, inform every essence of this volume, and yet all this knowledge is humorously presided over by a jive-ass, oratorical tone equal parts tent-preacher and pimp.

Given this reliance on interdisciplinary integration and stylistic confusion, it must be said that Kentucky Fried Tender is more aligned with a classic tome by Balzac than any postmodernist Rubik’s Cube Thomas Pynchon might produce. Rest assured, this is no deadening text: despite the book’s addled, schizophrenic form, it is no attempt to impart a fractured view of the modern human psyche by replicating, structurally, its television-and-Ritalin-embattled foibles (though there are a ton of pretty pictures and pie-charts nestled right next to the science). Nor is this anything you’d buy at the college bookstore or find doled out piecemeal to Modern Science, National Geographic or Harper’s. This is enlivening, nutritious entertainment; Dr. Currell’s is a dense, often obtuse omnibus that harkens back to a time before fiction, science, history and philosophy were compartmentalized onto separate shelves.

Even Currell’s voice betrays his seriously old-school roots; he persistently reminds us that only in the last century or so has literature eluded its oral tradition. His tone tells us that the literary word is not meant to be studied in monkish solitude, but, rather, experienced communally as it is shouted from the pulpits or shared on street corners. Imagine R. Kelly reworking Trapped in the Closet to include portions of the Odyssey after he’d wiled away his downtime with the Good Book and some PBS, and you get an idea of where, stylistically, Currell is coming from. He’s even recorded some passages over loungey jazz rhythms, and has presented his world-view publicly in classrooms and barrooms alike, replete with PowerPoint assistance, copious buckets of Original Recipe, and, of course, his white linen suit and bow tie.

Currell has given us a unifying tract that begins with the Word, examines our hunter-gatherer forebears, winds around Adam and Eve sucking pears in their garden, salutes the young bald-faced Abe Lincoln considering his candidacy, boy-howdys Colonel Sanders on his dirt-road march to millions, and lands squarely between the silicon filaments currently powering my laptop. Admirably, and with an impressive degree of success considering his scope, Currell strives to not only reference but also unify the definitive social, technological and culinary advancements made in this epochal timeframe, and does so with an omnipresent nudge and a wink above his mustache. “The direction is clear,” he writes, “life has moved from chaos to complexity, from 14,000 languages after the Tower of Babel, to 15,000 KFC’s all across the globe.”

Kentucky Fried Tender has its share of problems. It often smugly struts like the peacock through its purpose, leaving grand and vital leaps of ideology unexplained and up to conjecture. The colloquial, comic voice tends to obfuscate the author’s intended scientific or sociopolitical end, making the reader work a little too hard at times for what can amount to little informational payoff. That said, I do admire Currell’s refusal to hold a reader’s hand through his book; like any piece of philosophy, KFT requires that you bring much of yourself to the table in order to be nourished.

And, finally, the fictional-poetic parts often seem inconsequential compared to the impeccably researched and more fully-articulated chunks of scientific and scriptural knowledge; I often found myself merely tolerating these sections, wishing I was back in class learning just how Harland Sanders and the Lord of Hosts are inextricably linked. The fanciful prose can come across as overindulgent and self-satisfied, an attribute which points to what is truly unsettling about Dr. Currell’s book: how cross-eyed obsessive and offputtingly passionate it is at its very core of cores. Though there is something truly intoxicating and exhilarating about spending time with Currell in his weird, brainiac world of three-testicled sultans, mammary-centric (capitol-R) Religious experiences (it’s the parietal lobe, y’all), and all this relentless fist-raised testimonial to Colonel Sanders’ Universal Omnipotence, it can get a little disturbing after a while; you wonder, at times, if there’s even a joke to be in on. Sometimes Currell’s fervor brings to mind that bulge-eyed pervert you run into at the bar… when he inevitably starts froth-mouthed yapping about some girl he likes, you instinctively visualize which of her windowsills he’ll be drooling on later.

But here, it’s live by the sword, die by the sword: one of the tonal mixtures that works so well in this book is where relative scientific objectivity plays full-on grabass with an obsessive erotic ejaculation that evokes Barry White’s sweat-moistened cummerbund. Besides, nobody ever said literary innovation had to be pretty. All in all, this unique little tome should make Athens beam with pride: you didn’t know, girl, that, nightly, a new Herman Melville wanders your darkened avenues with grease gleaming in his smirk-broken mustache and a disconcerting bulge in his white linen trousers, now did you?

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.