While no one knows when a vaccine or tried-and-true therapeutics to treat COVID-19 will come to fruition, scientists are working quickly, diligently and in conjunction to help find solutions and treatments.

Science is written in pencil, not pen, and can often be a slow endeavor, but with so many researchers working on one problem all at once with such urgency, the research community is advancing scientific knowledge about COVID-19 at a rapid rate beyond anything in modern history. With each contributing scientific study, our understanding of COVID-19 grows, and, bit by bit, we are beginning to see a clearer picture about both how to limit the spread of the virus and what type of therapeutics could help treat the disease, and we inch closer to creating a viable vaccine.

At UGA, a variety of research has contributed to this growing wealth of scientific literature and knowledge. As a research community, UGA is at the forefront of this endeavor and has invested heavily in the concept of “One Health,” says Vice President for Research David Lee. One Health, as defined by the CDC, is an approach to research that “recognizes that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment.”

“This pandemic demonstrates the wisdom of UGA’s long-term strategic investments in One Health—including in infectious diseases, vaccine and drug development, public health and related areas,” Lee says. “These investments—which include faculty expertise, but also graduate student programs and state-of-the-art facilities and equipment—put UGA in a position to respond not only to this pandemic but also future outbreaks involving new viruses that many experts anticipate will threaten both human and animal health. Indeed, our faculty, staff and students working in these and other areas have stepped up and currently have dozens of studies underway that will provide greater insights into and more tools with which to fight COVID-19 and other pandemics.”

The Search for a Vaccine

At UGA, several world-renowned experts and research groups have been chipping away at a solution for the virus with research that seeks to find a vaccine for COVID-19. The website Successful Student recently listed UGA as one of the top 10 U.S. universities that are contributing to COVID-19 research projects.

College of Veterinary Medicine infectious disease expert Biao He has developed a COVID-19 vaccine candidate that has been successful in early test models. He hopes it will be ready for Food and Drug Administration approval by the end of the year.

His vaccine uses modified strains of a virus that causes kennel cough in dogs, known as parainfluenza virus 5, or PIV5, to produce the spike or crown proteins found in coronaviruses. When administered, cells are infected with PIV5, and the body defends itself against the spike proteins, eventually creating an immunity to the infection.

Scientists in Ted M. Ross’ lab at the College of Veterinary Medicine are also hard at work searching for new immunotherapies and a vaccine. Ross—who is best known for his work to develop a universal flu vaccine that would make seasonal flu shots a relic of the past—has been working with other researchers at UGA’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology to analyze the viral genome of COVID-19 and find targets that would prompt the immune system to create protective antibodies.

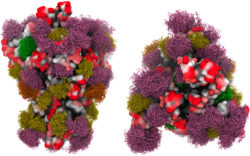

Over at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, Rob Woods and Parastoo Azadi have been investigating COVID-19’s exterior spike proteins, the “corona” that gives coronaviruses their name. The proteins play a big part in how the virus is able to infect human cells. Looking at the proteins and sugars on the surface of the virus, they have learned that SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins latch onto cells and force the virus through the cell membrane, a press release on their research notes. The human immune system detects foreign proteins like the spike protein by recognizing amino acid sequences. Sugar on the protein’s surface, however, can mask amino acids so antibodies can’t see them. Influenza and hepatitis C, for instance, behave in this way.

Woods says he was happy to report that their research—presenting computational models on the role of how sugars play a part on the viral surface—has recently been featured in two major journals: Nature Scientific Reports and Cell Host & Microbe.

“We have already had a lot of favorable feedback because the modeling provides truly unique insight into how knowledge of the 3D shapes of glycoproteins on the virus surface can be exploited in vaccine design,” he says.

The urgency of the problem at hand meant many late nights doing the research, which could be done remotely, but ultimately the resulting models may also be important for the future of vaccine research overall.

“Regarding hopes for a vaccine, the danger of the current pandemic has led to an extraordinary level of scientific engagement, producing some highly innovative strategies for vaccine design,” Woods says. “I think that not only will this lead to effective vaccines against COVID-19 in the near future, but in a bigger picture, I think it will lead to new thinking in the approach to vaccine design in general.”

Public Health Research

At the College of Public Health (CPH), a wide variety of research is helping to inform policy and management of the pandemic. From understanding how the disease affects hospitals to finding novel ways to keep an eye on outbreaks, much of the research coming out of UGA’s CPH is available for use in the real world now.

Grace Bagwell Adams, associate professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the CPH, has been working alongside a team of faculty and students who have modeled COVID-19 case surges for local hospitals. Started in April, the research continues to help hospital leaders anticipate personnel and equipment needs.

“The report was intended to inform [hospitals] about the initial wave of cases expected through April and mid-May,” says Bagwell Adams. “At the time, localized estimates of the epidemic curve were not available—only state and national estimates were being used to guide policy. Building on the work of doctors John Drake and Andreas Handel, our team estimated local disease growth for the critical-care teams to use in planning purposes at [Piedmont Athens Regional] and St. Mary’s. The report presented a range of estimates that might be expected during the first wave that allowed for hospital preparation in the areas of PPE, staffing and critical care beds.”

That initial wave of cases in the spring was followed by a short-lived respite in late May through early June, but regional cases have grown exponentially, and Clarke and surrounding counties have been classified in the “red” zone, according to the weekly White House reports in July and August, Bagwell Adams says.

“Recently, many surrounding counties have begun to slow in the growth of new cases, but Clarke continues to increase significantly,” she says. “The most notable state-wide case growth is in the 18–29 age range. Clarke’s latest data from the Department of Public Health show a 9.1% positive rate, which is nearly twice as high as it should be to control transmission,” according to World Health Organization guidelines.

A group of public health infectious disease epidemiologists has also been tracking and modeling local, state and national COVID-19 cases since May. As part of UGA’s Coronavirus Working Group, the public health group played a large role in sounding the alarms to leaders about the dangers of case surges if mask mandates on campus and robust testing weren’t implemented.

Andreas Handel, project lead and associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, says that while cases are trending down for the last month statewide, Athens continues to see increases. “The work I’ve done with my colleagues at Emory has been used by Emory University for their planning,” she adds. “This is the only certain use I’m aware of. Since we make all the work publicly available, it could—and I hope does—inform others, but I don’t know for certain.”

Outside of data on cases via testing, some other new research has emerged that may be beneficial in monitoring the pandemic and outbreaks. Researchers have been studying the effectiveness of using wastewater samples as surveillance of COVID-19. By extracting the virus from sewage and measuring its concentrations, researchers were able to get a fairly accurate estimate of infection trends that was a week ahead of diagnostic testing. The lab data is available weekly for the last few weeks. While the CPH provided funding to get the project started, the project is the collective effort of CPH and the Odum School of Ecology’s Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases. CPH Professor of Environmental Health Science Erin Lipp is the project lead.

“Right now, what this work does is show trends at the community level,” Lipp says. “It can augment testing that is already being conducted but has the potential to show changes in infection level before those may be obvious in the reported case data. This could give a heads-up to public health agencies and local officials that either a mitigation strategy is working or not, or that there may be a rise in cases on the way.”

The research still needs more examination to be able to relate levels in sewage to specific prevalence in the community because researchers are still learning more about how long those infected may shed the virus, but there have been some initial findings in recent weeks that are of note, Lipp says.

“From our data collected to date, we can pick up on some associations,” she says. “For example, virus levels in sewage began rising sharply around June 24. This was about three weeks after the state allowed a much broader re-opening. Conversely, while the change was modest, we saw virus levels in sewage start declining in July through Aug 4. The first Athens mask ordinance went into place on July 9. Sewage levels have been steadily increasing since Aug 4, even though reported cases had steadied or declined. This difference may be due to lags in reported cases. The timing of the increase coincides with students moving back to Athens, so a larger population as a whole, and precedes the recent uptick in reported cases.”

While researchers continue to research COVID-19 on a variety of levels at UGA, researchers have been hopeful that their findings help contribute to problem-solving in the local community and beyond. However, as seen by a recent letter to the AJC from four public health experts at UGA who noted that the campus was in “grave danger,” that research isn’t necessarily being taken into consideration by those with decision-making power. Nevertheless, researchers across campus continue to do their best to make a difference and provide their findings in hopes that they will help combat the Covid-19 pandemic.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.