This week’s installment begins with a little backtracking in Orth Stein’s life. After years of close escapes from the law, including an acquittal for murder and several for forgery, Stein’s luck finally ran out in Florida in the late 1880s. He was convicted, probably of forgery, and sent to the Marion phosphate mines as a convict laborer. During his time there efforts were made to secure a pardon for him, one of the chief workers in his behalf being his overseer, Mr. W.H. Price, who later said of Stein, “I never knew a brighter, more interesting fellow in my life.”

After his pardon in late 1890 or early 1891 Stein went to Savannah and immediately found work at a newspaper there. The story of his harassment by private detectives, his flight to Atlanta, and his arrest, release, and employment by the Journal has already been told. Stein began working for the Journal as an artist and reporter in October 1891. On Feb. 22, 1892, a St. Louis paper reported that Stein had been arrested in New York state for robbing a train. The Journal sent them a telegram: “Stein is at work here, as usual, this morning.” But Stein would not be in Atlanta for long.

Two days later the Savannah Press reported that a new illustrated weekly would soon be published in that city, to be edited by Orth Stein. On March 4 the Press announced that “Orth Stein, esq., is in the city today. Mr. Stein is the artist who will have charge of the new illustrated paper.”

The first issue of The Looking Glass appeared Saturday, March 19, 1892, in Savannah. Interviewed by the Press, Stein confidently predicted that his paper “would have many enemies before long.”

Stein was editor, reporter and artist for The Looking Glass. The publisher was Aaron B. Burk, who probably had partners in the enterprise. Its offices were in “The Looking Glass Building” at 96 Bryan St. Within a few months The Looking Glass was advertising itself as “a high-class illustrated journal” with the “largest circulation of any paper published in Savannah:” “an unsurpassed medium for advertising.”

Stein’s most characteristic and consistent trait was his enormous capacity for work, and he never tested that capacity more than in the summer of 1893. On June 21 J.H. Estill, owner of the Savannah Morning News, broke his agreement with his typesetters and hired a man who was not a member of the Typographers’ Union. The staff did not go out on strike: They quit. Within two weeks a new Savannah daily paper, the Morning Telegram, was announced. It was said to be a union shop paper in direct competition with the News, and its editor was to be Orth Harper Stein. The Looking Glass was still pretty much a weekly one-man show, but Stein did not hesitate to add to his burdens those of running a daily paper. Fortunately for his health and sanity, the Telegram went bankrupt in five weeks.

Stein continued to put out The Looking Glass every Saturday for several months. By the spring of 1894 he had moved the paper to Atlanta. Whether Stein’s Savannah backers abandoned him as too controversial, or whether he got a better offer from Atlanta investors I have not yet determined. Stein undoubtedly needed major financial suport for his lavishly illustrated paper, but who provided him this support in Atlanta remains a mystery.

We have already seen that Stein did not shy from controversy, but he was selective in the controversy he chose to stir up. A close look at the issues Stein chose to ignore may give us a clue as to who his “angels” were. Atlanta city politics in the 1890s were a chaotic tangle too complex to unravel here. Basically, two factions of capitalists vied for control of the city, each courting a large and sometimes militant working-class vote. These two groups were sometimes known as the Brotherton and English factors, after their most visible leaders. The first group represented the interests of Joel Hurt, real estate developer and owner of the city’s streetcar, electric and gas companies. The second group largely fronted for the interests of the Venable brothers, William and Samuel, developers and builders (and, incidentally, uncles of recently deceased KKK Grand Dragon James Venable of Stone Mountain).

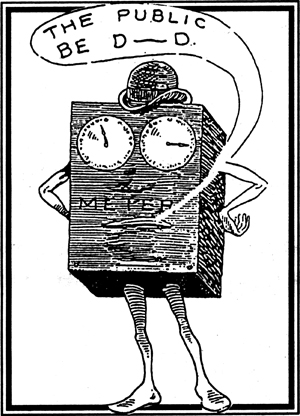

The Looking Glass was the constant and brutal scourge of Joel Hurt and the Brotherton regime from its first day in Atlanta. Hardly one issue of the paper failed to denounce Hurt as a gouger of the public, an exploiter of labor and a tax defaulter. Stein made public the slightest rumors and the most obscure documents available relative to Hurt and his political allies. On the other hand, The Looking Glass overlooked the $14,000 overcharge the Venables collected on a street paving bill. Stein supported their attempt to fob off an unprofitable hotel on the taxpayers as a new city hall. He maintained a discreet silence about the Venables’ occasional street brawls with personal enemies and labor organizers even though he was generally enthusiastic about writing up the fistic exploits of Atlanta’s elite.

Whether or not they paid his way, Stein served the Venables’ interests well.

© 1994 John Ryan Seawright

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.