Like unexploded ordnance buried beneath the surface of the university, Hue Henry’s long-anticipated bombshell of a book about UGA’s academic/athletic scandal has finally detonated.

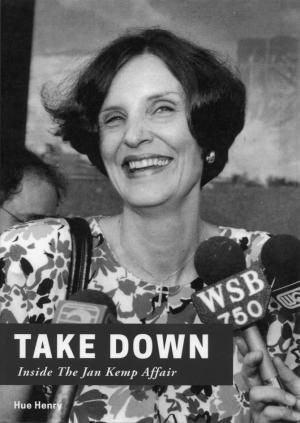

Take Down: Inside the Jan Kemp Affair is Henry’s recounting of the federal court case that exonerated and rewarded a whistleblower and dethroned a UGA president. The book is inside-football, told from the perspective of the surviving member of the legal team that represented Jan Kemp—Henry and Pat Nelson, his co-counsel, who died in 2007.

Take Down brings back a time when the UGA president, Fred C. Davison, was a tyrant who crushed opposition, rewarded sycophancy and ruled the university through lieutenants who served him rather than the school. His mission was to impose on the collegiality of scholars a corporate hierarchy that brooked no opposition and systematically eliminated those who objected, no matter how distinguished their standing.

If that description of UGA under Davison sounds unbelievable, read Take Down and be reminded how things were during the 19 years (1967-’86) Davison ruled UGA.

Here’s an excerpt from a column I wrote in The Athens Observer in 1980 about the firings of Davison opponents: “There’s a familiar pattern to the process. It usually happens between quarters, when nobody is on campus. A dean or a department head is called in for a meeting with Vice-President Trotter. Presidential Counselor Ralph Beaird is there. The meeting turns out to be not about the latest departmental plans but about relinquishing a position. It is quick. It is quiet. There are no screams. The body is disposed of quietly.”

The next year, Jan Kemp (no relation to Brian), head of the English department in the UGA developmental studies department, objected when she was ordered by her department head, Leroy Ervin, and Vice President Trotter to acquiesce in preferential treatment for nine scholarship football players who were needed for the national championship 1981 Sugar Bowl game.

The developmental studies program was set up to help students who were experiencing difficulty making their grades in UGA’s regular courses. Many of those students were athletes. Some were the children of influential alumni. University system policy dictated that students had four quarters to make their grades in developmental studies and then either be returned to the regular curriculum or dismissed from the university. Kemp objected when she saw her department’s procedures again overruled by her director and the vice president, with the acquiescence of the president. When she persisted, she was demoted and then informed that her contract would not be renewed—the same fate that had visited so many other deans and department heads.

The difference this time was that Jan Kemp refused to go quietly. Instead, she sued her department head, Ervin and his superior, Trotter. Kemp claimed that her freedom of speech was abrogated when she was fired for speaking out against the subversion of her program’s procedures by those in authority over her.

There was a Trumpish quality to the university’s management in those days, and it finally met its match in Henry, an Avenatti of an attorney, who already had a track record of successfully suing the university over other high-handed treatment of its employees.

Henry and Nelson filed the suit in federal court in Atlanta, where they thought a jury might be more objective in a case involving Georgia football. Take Down is a blow-by-blow, witness-by-witness account of that trial. It is not a scholarly history but reads like a conversation with Hue, as he tells you, sometimes repetitively, from his memory and from the trial documents and newspaper accounts how the lawyers sparred, how the judge directed the trial and how the witnesses did and did not tell the truth.

The $1 million verdict for Kemp was intended by the jury to send a message to UGA and any other school that would corrupt its own academic mission for athletics or for any other ulterior enterprise. UGA got the message. Davison was forced to resign, Coach Vince Dooley got the message, and the tutoring of athletes was reorganized. As we approach what we hope will be another championship year in football, so dependent on the academic eligibility of athletes, let us believe that those reforms are still in place.

Kemp’s premise was simple and straightforward: It is a grave disservice to young people to promise them a college education, knowing that they’ll never get one, and then use their athletic abilities for as long as possible before discarding the athletes as the academic failures they were always destined to become. In that light, it is disquieting to learn that UGA, at the end of the last football season, ranked dead last in the SEC in graduation rates for football players. Take Down should be the book of the year for Bulldog Nation.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.