The Hot Corner tops the preservation group Historic Athens’ 2020 Places in Peril list, but by next week it may not be in peril any longer.

A long-delayed Athens-Clarke County Commission vote on a local historic district for the western end of downtown is scheduled for Tuesday, Nov. 17. While victory for historic preservation advocates is by no means assured, it appears that enough commissioners support the district for it to pass.

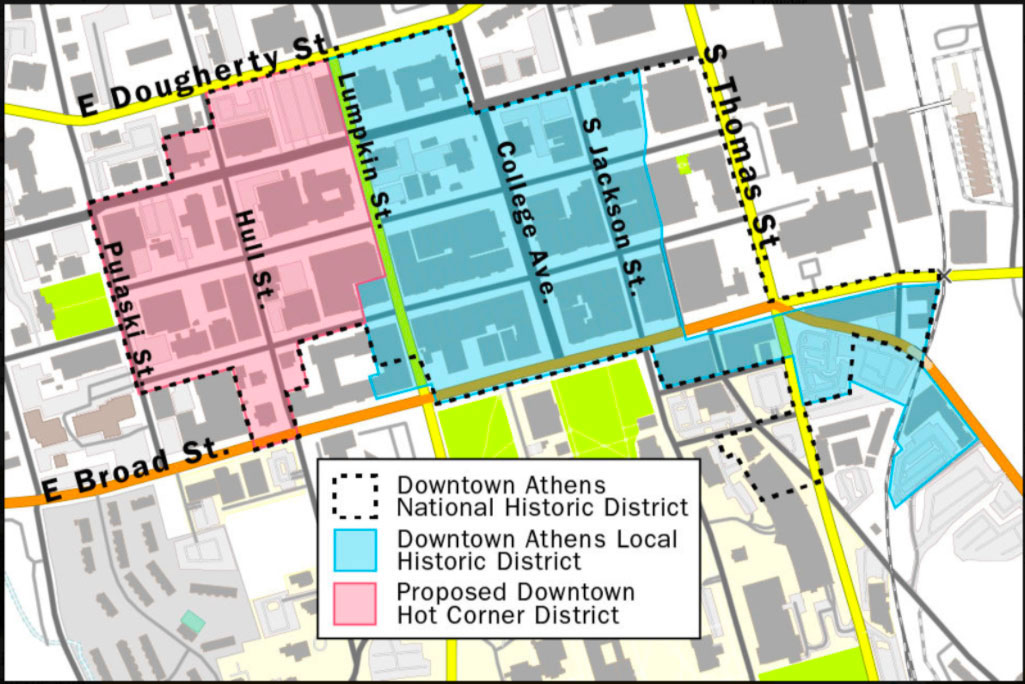

The portion of downtown west of Lumpkin street has a rich history as the center of Black commerce at the turn of the 20th Century, then as a hub for car sales and repairs as the automobile age began, and since the 1980s as the beating heart of the Athens music scene. Yet it was excluded from a local historic district created in 2006 that covers the older and grander buildings to the east of the Khaki Line, historically home to more upscale retailers than the largely blue-collar West End.

The West Downtown Historic District would be anchored by the Hot Corner at the intersection of Washington and Hull streets, home to the Morton Theatre, built by Monroe “Pink” Bowers in 1910 and restored by Athens-Clarke County in 1993 after it had fallen into disrepair. The Morton hosted vaudeville shows and legendary musicians like Cab Calloway, Blind Willie McTell and Bessie Smith and housed the offices of doctors, dentists, pharmacists, insurance agents and other Black professionals during segregation.

Before then, the area was, as Commissioner Melissa Link describes it, “kind of grungy,” populated by stables and blacksmiths. Bowers and other Black developers brought more upscale white-collar African-American businesses to the neighborhood. Several of those buildings were demolished in the 1960s and ‘70s, including the Samaritan Building, designed by Lewis H. Persley, the first certified Black architect in Georgia. Similar in style to the Georgian Hotel, “it was probably one of the most elegant buildings in downtown Athens,” Link says.

White developers and white-owned businesses soon moved in. The 100-year-old Saye Building at the corner of Hancock Avenue and Lumpkin Street, for example, is one of the few Art Deco structures in Athens. It was once the headquarters of the Southeastern Stages bus company, which also built the Art Moderne-style bus station on Broad Street that’s now Chuck’s Fish. “It showed the modern forward thinking of the transportation industry,” Link says.

In fact, it was the Saye Building that prompted Link to propose the West Downtown Historic District in January 2019. Its current owner, First United Methodist Church, planned to tear down the building for a parking lot—the same fate as the Samaritan Building, among others.

By the 1920s, West Downtown was transitioning into auto-centric uses, with service stations, tire stores and machine shops. In the past decade or so, they’ve been replaced by entertainment-oriented establishments like Creature Comforts, Ciné and Ted’s Most Best, but all of those businesses have retained the buildings’ automotive character.

As Historic Athens Executive Director Tommy Valentine points out, most, if not all, of the music venues downtown are in rehabilitated historic spaces. The 40 Watt Club was once a grocery store, and the Georgia Theatre started out as a YMCA. Recently, though, the music scene lost a landmark venue in Caledonia Lounge, which is located within the proposed district.

Although the closing of Caledonia and nearby consignment store Atomic had nothing to do with the threat of redevelopment, and a historic district wouldn’t have changed anything, it demonstrated again that beloved longtime locally owned businesses are always under threat. News that the next-door bar Church would take over those spaces created a furor. “What you saw is how passionate people are about this side of town,” Valentine says. (See the story on p. 10 for more.)

“If we lose access to spaces that size, we lose access to those funky holes-in-the-wall,” Valentine continues. But a historic district would create an extra layer of oversight over new development, requiring approval by the Historic Preservation Commission, ensuring that any new construction fits in with the surroundings.

That’s important because ACC’s downtown design guidelines “thoroughly suck,” according to Link. “It’s as much about protecting the future as it is about preserving the past,” she says.

The district has met with some pushback, though, most notably from churches and David Montgomery, a Lexington lawyer who owns the “telephone building,” the three-story yellow building on Clayton Street. Montgomery has argued that the historic district will hurt property values if owners, particularly Black owners, decide to sell.

Due to opposition from the owners, Link removed those buildings on the Manhattan Café block—they only date back to about 1970, anyway, she says—as well as First Methodist. Link’s map also adds the building housing Flicker Theatre & Bar, owned by Drew Dekle, as a contributing property. Outlying churches were already taken out of a much larger district county planners proposed. The local district lines closely follow the National Register of Historic Places.

Opposition to historic districts is common at first, Valentine says, but once property owners learn more about the benefits, they usually come around. Unlike the National Register, which offers little more than recognition, local historic districts come with a property-tax freeze, as well as access to state and federal grants and tax breaks.

Still, not everyone is happy. Commissioner Allison Wright has said she will make a motion that property owners be allowed to opt in or opt out of the district. However, that proposal is “of dubious legality,” Valentine says, because historic districts must be contiguous, and Wright’s proposal would create a bad precedent that commissioners have been unwilling to set with 16 previous districts.

Other properties listed as 2020 Places in Peril are:

357 South Milledge Ave.: This former Beta Theta Pi and Sigma Pi fraternity house has been boarded up since it failed to meet the ACC fire code in 2004. But like most Tudor-style houses, it was built to last. The house is distinguished by its earth tones, multi-paneled windows and half-timber facade.

Sandy Creek Pumping Station: Hidden in the woods along the North Oconee River Greenway is this architectural gem, with Roman details and arched windows reminiscent of City Hall. Built by architect and city engineer J.W. Barnett in 1916, the pump station brought water from a reservoir to the growing population of Athens. It sat unused and inaccessible until the construction of the Greenway and a pedestrian bridge over Sandy Creek, and it remains neglected.

St. James Baptist Church Cemetery: Tucked away off Roberts Road in the northwestern part of the county, this 19th Century African-American cemetery is overgrown, undermarked and in need of care to ensure the proper respect for those interred within. The cemetery includes the graves of people born into slavery, sharecroppers, more prosperous individuals and veterans. Some are marked with hand-carved stones, some with granite monuments, and others’ identities have been lost to time.

Judia C. Jackson Harris School: The first J.J. Harris—a much newer elementary school currently bears the name—was also known as the Model and Training Institute and was one of the first suburban schools for African Americans during the Jim Crow era. A fire burned down the original three-room wooden schoolhouse in 1925, but Black and white residents worked to rebuild it. They received help from the Rosenwald Fund, founded by Jewish businessman and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald to build thousands of Black schools across the South.

2019 Places in Peril: Historic Athens and other organizations have made progress on some of the properties named to last year’s list. Funding is set aside in SPLOST 2020 to turn Beech Haven, a 149-acre wooded area along the Middle Oconee River amidst Atlanta Highway’s sprawl, into a city park. Winterville installed signage at the recently rediscovered Central Baptist Church cemetery. Preliminary talks with the ACC government are underway to create a local historic district around the old mill town of Whitehall Village and preserve a historic Black schoolhouse at Billups Grove Baptist Church. Greater Bethel Baptist Church is currently fundraising to restore the Frank C. Maddox Center, an old American Legion post, based on plans drawn up by local architectural firm Arcollab with church and neighborhood input. Work to preserve the Reese Street School, now used as a Masonic lodge, is ongoing, as well.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.