Not far from Athens lies Watson Mill Bridge, the longest remaining covered bridge in Georgia. Few people today are aware of its importance in local black history. Built in 1885, it allowed wagons to carry corn across the south fork of the Broad River to the grist mill owned and operated by Gabriel Watson. Today, the restored bridge is still in use, its utility equaled by its weathered beauty.

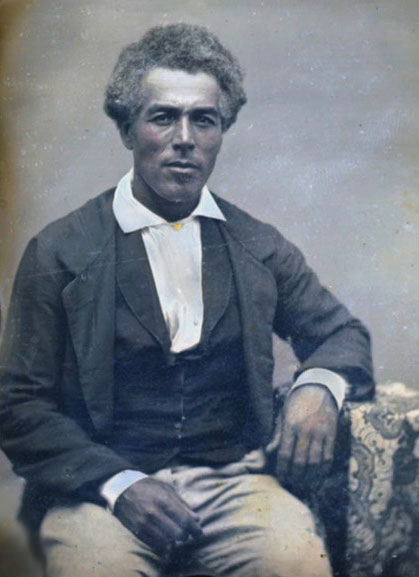

The story of Watson Mill Bridge begins much earlier, though, in 1829, with a slave sale in South Carolina. John Godwin was a wealthy contractor from the Cheraw District on the Pee Dee River. When one of his neighbors died and the estate was liquidated, Godwin bought Horace King, his mother Susan and his siblings. Horace was 22 years old and of mixed ancestry, being African-European on his father’s side, and African-Catawba Indian on his mother’s. The young man was not only able-bodied, but a quick study in the science of engineer Ithiel Town’s “lattice truss” bridge construction. By 1832, when Godwin won a contract with the new town of Columbus to build a 400-foot bridge across the Chattahoochee River, King had become an integral part of the Godwin Bridge Company.

John Godwin and Horace King moved to Girard, AL, across the river from Columbus. After successfully completing the project, they began to win contracts all over those parts of Georgia and Alabama then considered the Southwest frontier. River villages were growing into towns and wanted crossings that were more expedient than ferries. By the 1840s, the reputation of the Godwin Bridge Company attracted the attention of a wealthy planter and lawyer named Robert Jemison Jr. He went into business with Godwin as the company’s lumber supplier. Observing King’s skills as supervisor of the company’s many large projects, Jemison wrote to Godwin that he was “pleased to add another testimonial to the style and dispatch with which Horace King has done his work as well as the manner in which he has conducted himself.”

By 1845, however, Godwin was having financial trouble due to his investment in a failing railroad line. Jemison offered to help him by buying Horace King for $6,000 (approximately $145,000–$200,000 today). Some accounts say that King, who had been allowed to keep his contracting income, bought his own freedom from Godwin. However, freeing one’s slave had been made deliberately difficult with complex manumission laws. We do know that Godwin first moved to Ohio with King and freed him under Ohio state law. Then they returned to Alabama, where Jemison, a state senator, pushed King’s emancipation through the Alabama General Assembly. As of 1846, Horace King would never again face the threat of being sold to settle a master’s debts.

The three men—Godwin, King and Jemison—continued their construction projects together, but Godwin didn’t regain his former prosperity. When he died in 1859, King erected a tall marble column on his grave which read “… placed here by Horace King, in lasting remembrance of the love and gratitude he felt for his lost friend and former master.”

The stereotype of a kindly former master taking care of his dependent former slave was inverted by the Godwin-King friendship. Godwin’s children asked King to manage their late father’s sole remaining asset, a large sawmill in Girard. With a possible war of secession on the horizon, Godwin’s heirs worried that King might yet be seized to settle their father’s debts, despite his double emancipation. They went to the county courthouse and formally recorded that King was an emancipated man and “freed from all claims held by us.”

Like ripples in the river above Watson Mill Bridge, the ensuing successes of the King family circled out from the love between Godwin and King. Horace King founded his own bridge construction company and employed his five children in the firm. The Civil War slowed them down, but when it was over, the King family was sought out to rebuild bridges that had been damaged or destroyed in that conflict across Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi.

By 1871, Horace’s oldest child, Washington King, had a prominent role in the bridge company and was living with his family in Athens. That same year, Gabriel Watson bought a nearby grist mill on the south fork of the Broad River. It had been in place for many years, but Watson gradually expanded the operations to include flour and corn mills, a wood shop and a cotton gin.

In 1885, the county awarded Washington King the contract to build a bridge. The resulting 228-foot long span was called a “kissing bridge” because its covered length allowed sweethearts time for a bit of romance in the crossing. It was punctuated with a large window that let in light and created a draft that kept the interior dry. Washington King improved plans for the bridge by requiring that the exterior weatherboarding be planed to better shed water, and by designing the approaches. He was lauded by the county for going above contractual duty in providing these improvements.

The mill that spurred the bridge construction ceased operation, but this peaceful place on the river was not abandoned. The fact that it was built by a black man seems to have figured into its use during the segregationist decades of Georgia. According to the Rev. Franklyn Hall of Colbert, the water above Watson Bridge was a swimming hole for black children for many years.

“Oh, yes” said Hall, 80, “there’d be 25 or 30 bicycles all around that bridge, and we’d dive from that window. The Lord must have protected us because sometimes we’d even climb up on top and dive from the roof.” There could have been tree stumps and anything else in the water.”

In contrast, Hall said, the Broad River Bridge on Highway 172 was where white boys went swimming. In 1964, that bridge became notorious when the Athens Ku Klux Klan murdered Lt. Col Lemuel Penn there.

Most of the King family’s covered bridges are gone now. Wood is not as durable as steel, and age conquers all.

The covered bridge built by Washington King over the North Oconee River in Athens became fondly known as “Effie’s Bridge” due to its proximity to the infamous brothel run by Effie Matthews. When it was sold in 1964, there was great public outcry. The Stone Mountain Memorial Association bought it for a dollar, moved and restored it, and the bridge built by the son of a former slave is ironically now part of the world’s largest tribute to the Confederacy. This odd coupling became more balanced in January 2019, when the Stone Mountain directors gave attribution to the bridge’s origin by renaming it the Washington King Bridge.

Watson Mill Bridge still stands on its original site, spanning the south fork of the Broad River, and connecting Madison and Oglethorpe counties. For well over a century, it has been a place for pleasant social events like family reunions, weddings and picnics. During hot summer months, people enjoy splashing in the cool water flowing over the rugged shoals, which are a frequent destination spot for Athens cyclists.

The state park around the bridge serves as a wildlife sanctuary and has expanded to include hiking trails, horse trails, log cabin rentals, canoeing and camping areas. These activities attract many visitors, but none leave without viewing the magnificent old covered bridge built by Washington King, son of Horace King, the master bridge builder of Georgia.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.