“After the press reported that I had doubts about the [Oswald-was-the-sole-assassin theory], Dorothy Kilgallen called and invited me to meet with her at her Manhattan townhouse. She was the one reporter of my acquaintance who told me that she did not believe that Oswald was the sole murderer and who said that she was going to persevere until she discovered who was involved [in assassinating President John F. Kennedy]…Miss Kilgallen said that she was seriously committed to the case and that the Government was seriously committed to preventing the truth from being known.”—Mark Lane, A Citizen’s Dissent (1968).

“[I]f [Dorothy Kilgallen] was murdered, the crime was done to silence her, by a…representative of whatever faction it is that did not want the facts about the JFK assassination to emerge.”—Lee Israel, Kilgallen: A Biography (1979)

Single Assassin Rejected

Dorothy Mae Kilgallen (1913-1965) was for a time perhaps the best-known female newspaper reporter and columnist in the United States. Her specialty: crime reporting.

In the months following the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas, TX, on Nov. 22, 1963, Dorothy Kilgallen was one of the handful of American journalists who publicly expressed skepticism of the theory, peddled by the FBI and almost universally embraced by the American press, that Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone, had assassinated JFK. The official investigation being conducted of the assassination, she insisted in her widely syndicated columns, was pitifully inadequate. The assassination, she told friends, “had to be a conspiracy.”

Kilgallen’s columns were also disdainful of a second FBI theory (also widely accepted by the media) that Jack Ruby, the sleazy owner of a honky-tonk strip joint who murdered the handcuffed Oswald in a Dallas police station on live TV two days after JFK’s assassination, was not involved in organized crime and had shot Oswald for purely personal reasons and without the knowledge, encouragement or assistance of anyone. There was, Kilgallen asserted, “something queer” about the killing of Oswald. Jack Ruby, she maintained, was a gangster with ties to local police, and his murder of Oswald was a Mafia rub-out. In a column published exactly one week after the President’s assassination, Kilgallen wrote: “I’d like to know how, in a big, smart town like Dallas, a man like Jack Ruby…can stroll in and out of police headquarters as if it was a health club at a time when a small army of law enforcers is keeping a ‘tight security guard’ on Oswald. Security! What a word for it!”

When the Warren Report, which swallowed whole both of these now discredited FBI theories, was released in September 1964, Kilgallen called it “laughable.” She also continued her own probe of the JFK assassination, telling her friends that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy and that she would soon have the scoop of the century when she published a book disclosing the real story of the assassination. Within months, the 52-year old Kilgallen died an unnatural death under suspicious circumstances.

Convinced of Conspiracy

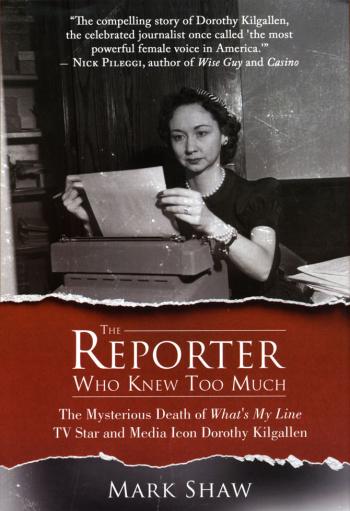

Mark Shaw’s The Reporter Who Knew Too Much (Post Hill Press, 2016), is an excellent biography of Dorothy Kilgallen with two focal points: (1) Kilgallen’s own inquiry into, and her published writings about, the JFK assassination and (2) her mysterious death, which author Shaw says was not an accident or a suicide, but murder. The investigation of the JFK assassination by a famous crime reporter who thought the assassination resulted from a conspiracy, Shaw concludes, probably led to Kilgallen’s murder by unknown persons who tricked or coerced her into consuming a lethal dose of prescription drugs.

Before reaching this conclusion, Shaw draws our attention to a number of relevant, mostly little-known facts, including the following:

• In July 1959 Kilgallen became “the first reporter to allege that the CIA and organized crime were teaming up to eliminate [Fidel] Castro.”

• Just before Jack Ruby’s murder trial began, Kilgallen in a February 1964 column noted that the Government had refused to provide Ruby’s defense counsel with certain requested information concerning Lee Harvey Oswald. She described the refusal as “Orwellian.” “[I]t does make you think, doesn’t it?,” she commented. “It appears that Washington knows or suspects something about Lee Harvey Oswald that it does not want…the rest of the world to know…Who is Oswald anyway?” Kilgallen was therefore one of the first journalists in this country to suggest, contrary to what the FBI claimed, that Oswald had not been a lone nut whose pre-assassination activities were below the radar of the U.S. intelligence community.

Kilgallen attended and covered Jack Ruby’s March 1964 murder trial. She was the only reporter to privately interview Ruby. (There were two such interviews, each lasting about 10 minutes.)

In August 1964, in an astonishing exclusive, Kilgallen published the then-classified transcript of the testimony Jack Ruby had given at a secret session of the Warren Commission two months earlier. (The transcript, leaked to Kilgallen by an undisclosed source, startled the public for two reasons. First, it revealed that the questioning of Ruby by Commission members—the men chosen to officially investigate and report on the murder of an American president—had been shockingly inept. Second, it disclosed that even though Ruby told the Commission that “I want to tell the truth, and I can’t here,” and that “maybe certain people don’t want to know the truth that may come out of me,” the Commission without good reason had flatly turned down Ruby’s earnest plea to be transferred to a jail outside the state of Texas, where he could speak freely.)

Suspicious Circumstances

After Kilgallen announced that she was gathering evidence to expose the conspirators behind the assassination, she came under FBI surveillance, and her phones were wiretapped.

Both the FBI and the CIA kept secret files on Kilgallen, in part on account of her interest in the JFK assassination.

In the weeks preceding her death, Kilgallen received death threats and was fearful for her life.

In connection with her investigation of the JFK assassination, Kilgallen compiled, kept careful watch on, and sometimes carried around with her, a thick folder of documents relating to the assassination. She refused to allow anyone to look at the contents of the folder, but did tell friends that “if the wrong people knew what I know, it would cost me my life.” After her death, this folder was never seen again.

Kilgallen was found dead in a bedroom in her New York City townhouse on Monday, Nov. 8, 1965. Her close friends, including the friend who discovered her dead body, thought she had died somewhere else. They also thought the scene in the room where she was found was abnormal and had been staged. She was in a room she never slept in and in a bed she never used. (Kilgallen had once caught her unfaithful husband committing adultery with another woman in that very bed in that same room.) She was positioned in the middle of that bed, which was described as “spotless.” She was still wearing the makeup, hairpiece and false eyelashes she always took off before going to bed. She was dressed in clothes she never wore when going to sleep. The book she allegedly had been reading was not in the right position it should have been in if she had laid it down before falling asleep.

Following the autopsy, the medical examiner gave the cause of Kilgallen’s death as “Acute Ethanol [alcohol] and [prescription] barbiturate intoxication. Circumstances Undetermined.”

Kilgallen was not an alcohol or prescription drug abuser.

One of the drugs found in her system was Tuinal, a powerful, dangerous barbiturate containing amobarbital sodium, a sedative-hypnotic, for which Kilgallen had no prescription. Doctors strictly forbid patients from using that drug if they are also consuming alcoholic beverages.

Kilgallen had a prescription for the barbiturate sleeping pill Seconal, and would take two capsules nightly. However, the amount of secobarbital sodium (the active ingredient of Seconal) found in her bloodstream would have required she ingest 15 to 20 capsules. Kilgallen definitely was not suicidal and could hardly have taken this many capsules by accident.

The “circumstances undetermined” language in the autopsy report may have been due to unanswered questions the examiner had about (1) where the Tuinal had come from, and (2) whether Kilgallen had ingested the drug knowingly and willingly.

Some of the officials in the medical examiner’s office thought Kilgallen had been murdered and that her corpse had been moved before it was found.

The police investigation of Kilgallen’s death was perfunctory.

Strengths and Weaknesses

A great strength of The Reporter Who Knew Too Much is that the author, like most of today’s authoritative students of the JFK assassination, rejects the sole assassin theory. The true believers in the “Oswald Alone” theory, Shaw astutely observes, “fit certain facts to the conclusions [they] wanted to reach and [have] dismissed credible facts in opposition to those conclusions.”

A weakness of the book is the author’s basic assumption that the Mafia alone was responsible for the JFK assassination. It is certainly true that organized crime figures may have been part of the conspiracy behind the assassination. But not even the Mafia could have carried out the assassination without the connivance of the Secret Service (responsible for presidential protection), the FBI (in charge of domestic intelligence) and the CIA (in charge of foreign intelligence). President Kennedy’s murder undoubtedly was due to a conspiracy, but at most the Mafia could only have been one part of it.

The Reporter Who Knew Too Much is one of many books, articles, blogs, and websites claiming there have been strange or suspicious deaths that appear to be linked to the Kennedy assassination. Fifty years ago, in chapter 16 (“Death and Misadventure”) of her classic and still very valuable book Accessories After the Fact (1967), Sylvia Meagher was one of the first researchers to make such a claim. She discovered that of 16 dead witnesses involved directly or peripherally in the assassination, 12 had been victims of accident, suicide or murder. (A 17th witness, Meagher also discovered, had been the victim of an attempted murder but had miraculously recovered after he was shot in the head at his workplace by an unknown intruder hiding there.)

Although some of the claims of suspicious deaths are erroneous or exaggerated, it is nonetheless a provable fact that, beginning with the murder of Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit less than an hour after the assassination and then the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald 48 hours later, an unusual number of witnesses, investigators, and other individuals connected in some way to the assassination died violently, unnaturally, or mysteriously.

Two books which list and discuss various of these deaths are Craig Roberts and John Armstrong, JFK: The Dead Witnesses (1995), and Richard Belzer and David Wayne, Hit List (2013). While both these books do get some important facts wrong, on the whole they are helpful and reliable information sources—and they are eye-opening for the dubious.

Donald E. Wilkes, Jr. is a Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Georgia School of Law, where he taught for 40 years. He has published more than 100 articles in Flagpole.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.