John Steinbeck once said that “socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” Yet, in tough economic times, it seems that the poor and working class always suffer more than those on top of the socio-economic ladder. On the flip-side, the poor also seem to gain less during the good times, which seems decidedly unfair. Are we a nation of CEOs or a nation of struggling day-laborers and desperately indebted regular people, digging in with their fingernails trying to avoid a long, slow slide to the poor house?

A Popular Idea

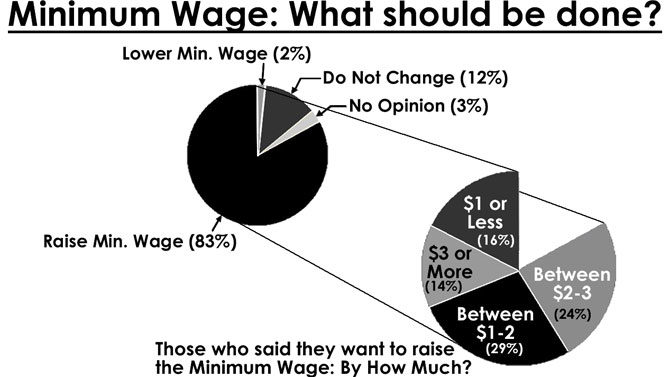

I visited 20 locations around Athens, mainly grocery stores where a cross section of people shop, to conduct an unscientific survey of about 100 people’s opinions on the minimum wage. I found that 83 percent favored raising the minimum wage, and most wanted to raise it significantly above the current $7.25 an hour. The median amount favored was $9, and the average was closer to $10. Majorities of all demographic groups—men, women, white, minority, UGA students—supported the concept.

A recent 11Alive poll found that 75 percent of Georgians support raising the minimum wage, and 60 percent want to raise it to at least $9. A Gallup poll, also from 2013, found 71 percent support nationwide for raising the minimum wage to $9.

Inflation was the main concern of those surveyed that opposed raising the minimum wage, but that concern is not necessarily valid. Costs like inventory, rent, utilities, insurance and employee health care generally comprise a large share of business costs, and these factors would not be much affected by a higher minimum wage. The Political Economy Research Institute did a study of Arizona’s referendum in 2006 to raise the minimum wage to $6.75 from $5.15 an hour (then the federal minimum). They discovered that even in an industry with as many minimum-wage workers as fast-food, prices would only need to rise by 1.7 percent to fully cover the higher wages. A $2 hamburger would cost $2.03. In other businesses, such as the hotel industry, prices would only rise by 0.8 percent. The referendum passed 65 percent to 35 percent.

Unemployment is a concern that was barely mentioned by the people I interviewed but is of great concern to economists. Classical economics dictate that raising the price of any commodity, even human labor, means that consumers of that commodity—business owners in this case—will demand less of it. Anyone can see that raising the minimum wage to $1,000 per hour is probably not a great idea. No business could possibly afford to pay all of their employees so well—only their CEOs—and would shut their doors rather than pay the labor costs. But what about small boosts, slowly over time?

Expert opinion on this topic has changed. In 1978, a survey showed that 90 percent of economists thought that a higher minimum wage would cause unemployment among low-skill workers. But in 1994, economists David Card and Alan Krueger published a seminal study showing that increasing the minimum wage in New Jersey actually increased employment relative to neighboring Pennsylvania. This led to a flurry of case studies, allegations of bias by detractors, even more case studies and meta-analysis of groups of case studies. In 2008, as the dust started to settle, researchers H. Doucouliagos and T.D. Stanley concluded that raising the minimum wage didn’t affect employment much at all. The connection (or lack thereof) between employment and the minimum wage is far from settled today.

The Politics of Wages

In his January State of the Union address, President Obama proposed raising the minimum wage to $9 by the end of 2015. Yet with Congress as divided as ever, a federal minimum wage increase is unlikely. Many states and local communities are stepping up to raise the minimum in their areas themselves. The state of Washington, for example, has the highest statewide minimum wage in the country at $9.19. The District of Columbia passed a living wage ordinance this July, despite the disapproval of Walmart, which had planned to open at least three stores in the area. (How shocking!)

In contrast, the Georgia minimum wage has been stuck at $5.15 for quite some time, although state Reps. Spencer Frye (D-Athens) and Kimberly Alexander (D-Hiram) have sponsored a bill, HB 681, which would raise the minimum to $9.80 per hour by 2018. While it is good to have a backup plan should Obama’s initiatives stall, HB 681 doesn’t have much chance of passing through the Republican-controlled Georgia Legislature. What else can we do?

Some cities have already taken action, such as San Francisco and Santa Fe, NM, have raised their minimum wages to more than $10. Many large cities throughout the country have higher minimum wages than the surrounding areas, helping to make up for the higher cost of living there.

In Georgia, it doesn’t quite work like that. Atlanta has the same minimum wage as any tiny community in the north Georgia mountains due at least in part to an organization called ALEC.

The American Legislative Exchange Council is a right-wing group founded in 1975 that connects corporate interests and state lawmakers. They advocate laws like the notorious “Stand Your Ground” and have promoted a bill called the “Living Wage Mandate Preemption Act” in many states around the country.

In 2004, when the Georgia Living Wage Coalition, working with Athens’ own Economic Justice Coalition, was pushing for higher wages in Atlanta, the Georgia legislature stepped in to prevent the city from passing a mandatory minimum wage increase with HB 1258. That law is nearly identical to ALEC’s Living Wage Mandate Preemption Act. When Atlanta tried again the following year with a voluntary living wage bill giving preference to contractors who were already paying higher wages, ALEC struck again with HB 59, which says that no local government in Georgia can “award preferences on the basis of wages or employment benefits” to any contractor it hires. The House sponsor of that law, Earl Ehrhart (R-Powder Springs), was elected chairman of ALEC in 2005, and the Senate sponsor, Chip Rogers (R-Woodstock), was then the treasurer of ALEC and is now an executive at Georgia Public Broadcasting making a living wage of $150,000 per year.

Corporations have told our state government to control the way we spend our own money in our local communities. The Georgia AFL-CIO said HB 59 set a “dangerous precedent for the state to intervene in the affairs of local government.” Yet this somehow passes for ALEC’s self-proclaimed mission of “limited government.”

A new group is forming to reclaim ownership over our local tax dollars and to combat ALEC in Georgia. This group, called Georgians for Local Economic Control is a decentralized network of activists across the state with one goal in mind: repeal of HB 59 and HB 1258. We welcome all who wish to join us in promoting local control. Please e-mail us at [email protected] for more information or visit the GLEC Facebook page.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.