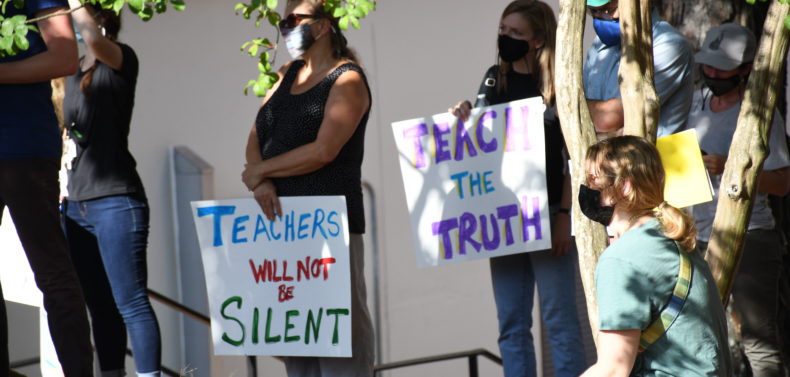

Dozens of Clarke County School District and University of Georgia teachers, parents, students and other community members weathered the smoldering temperatures Aug. 27 to protest the Georgia Board of Education’s recent resolution banning teaching critical race theory, or CRT, in K-12 schools. With their June vote of 11-2, Georgia became one of almost 30 states to enact regulations suppressing race curriculum.

“Racism is divisive. Racism is anti-American. Teaching students about it is not,” lead organizer and former CCSD teacher Amelia Wheeler said. “What is actually unifying and empowering is learning about movements for justice against these forces.”

Critical race theory, developed by academics in the 1970s, is the idea that racism is neither natural nor inherent to individuals. Rather, legal systems that perpetuate discriminatory practices have fostered the racism plaguing United States history. Conservatives tend to be unfriendly towards CRT curriculum; Gov. Brian Kemp praised the state school board for its decision to shield Georgia students from “dangerous, anti-American ideology.”

“CRT is something that says that racism is not just bad individuals. It is a structural problem baked into the way that our country runs, and so it means that it’s not up to any one of us to end it, but we’re all part of the system in various ways, so we have to come together to rework the system,” Wheeler said.

Speakers included Cedar Shoals High School English teacher Brent Andrews, chaplain Cole Knapper, Athens-Clarke County Commissioner Jesse Houle, Athens Anti-Discrimination Movement President Mokah-Jasmine Johnson, and Hattie Thomas Whitehead and Bobbie Crook of the Linnentown Justice and Memory Committe. Brumby Hall, where the protest was held, is one of the dormitories standing on what was formerly Linnentown, the Black neighborhood where the University of Georgia forced out residents in the 1960s and bought the land for student housing.

“We were tortured. We were terrorized, with closing off the streets, digging ditches we had to jump over when we were children to get home inside our houses, starting up heavy equipment at 12 o’clock at night running close to our houses. No one came from the city of Athens or UGA to speak with the adults in the community. We did not know anything,” Thomas Whitehead said.

Athens-Clarke County has responded to multiple demands made by The Linnentown Project, though the University of Georgia remains largely silent. Speakers like Johnson and Wheeler emphasized that the CRT ban puts Linnentown’s story at risk of being neglected and subsequently forgotten in CCSD schools, where many students are descendants of the families who lived there.

Rachelle Zola came to Athens from Atlanta specifically to support the demonstration. As a retired teacher who incorporated CRT and education on race relations into her curriculum, she jumped at the opportunity to voice her disappointment at the attempt at suppressing it.

“What critical race theory is is looking at systems that are in place that are hurting people,” Zola said. “It’s not about guilting your white kids, it’s just telling the truth about history. In this country, we have not been good at it.”

Former CCSD student teacher and North Georgia educator Morgan Tate channeled her passion for the cause into work as an attendant—setting up the sound system and canvassing the pine straw strewn area equipped with water bottles and $5 Starbucks gift cards for teachers. Neglecting race while teaching history is deceitful, she says.

“You can’t talk about United States history, which I taught, or world history without bringing in the fact that race becomes important. I don’t know how you talk about the Civil War and not talk about race,” Tate explained. “It would be ignorant and impoverished education, and a disservice to students.”

In addition to signs, protesters held flyers with QR codes passed out by Tate and fellow ambassadors. One of them directs teachers to an educator’s research guide with information about defining CRT, investigating policy against it and accessing lesson plans.

“We wouldn’t have the problems we have today if CRT was taught in schools. So I think the next thing is connecting with educators and helping them receive resources to do the work that needs to be done for students,” Tate said. “We perpetuate systems if we don’t address them.”

The new legislation is a resolution, meaning it doesn’t carry the force of law. Still, that doesn’t mean administrators can’t police it, and Wheeler said it’s only a matter of time before education on CRT becomes punishable by law, which is why “we need to be mobilizing and standing together now.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.