The COVID-19 situation in Athens is not improving. Clarke County continues to see a surge in cases, additional deaths and a sustained critical care bed shortage.

To date, Athens has had 2,166 confirmed cases since mid-March, with 143 hospitalizations and 19 deaths attributed to COVID-19. It took four months to reach 1,000 positive tests, but less than four weeks to double that number. The positive percentage—which health experts say should be at or below 5% to control the virus—continues to average about 12% statewide. Four Athens residents have died of COVID in the past two weeks, not to mention deaths and cases from other communities that rely on Athens’ two hospitals.

How are Piedmont Athens Regional and St. Mary’s coping with all of this extra stress? It depends on whom you ask. Administrators contend that local hospitals are still operating relatively smoothly, and that contingency plans for higher volumes of patients are in place.

Health-care workers, however, report a different picture from the inside. The system, they say, is beginning to show some cracks. The stress of everyday care now that businesses are reopened and people are getting back to day-to-day life, coupled with increasing numbers of COVID-19 patients, are taking a toll on health-care workers and the system itself. Many are concerned about how the arrival of UGA’s student population in the coming weeks will further stress the system.

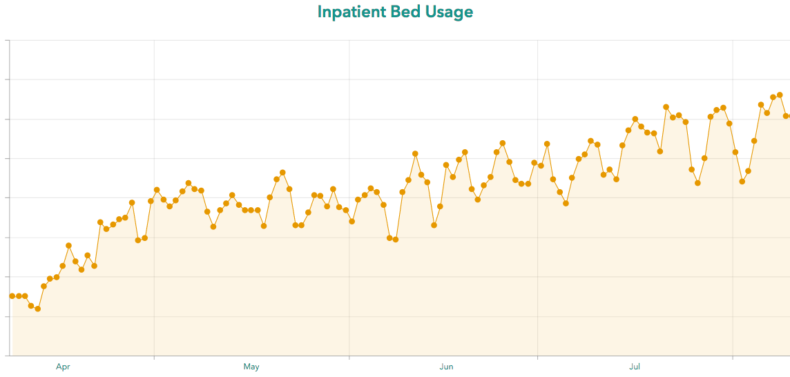

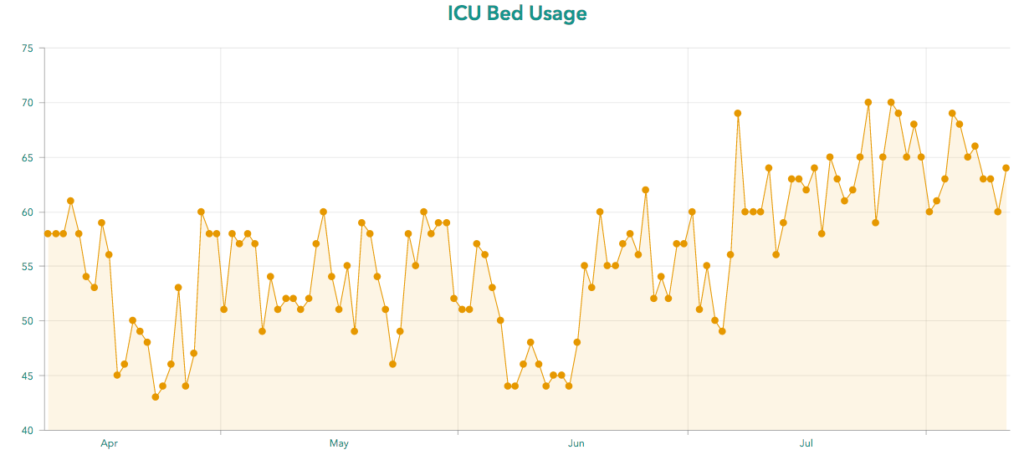

The Data Tells a Story

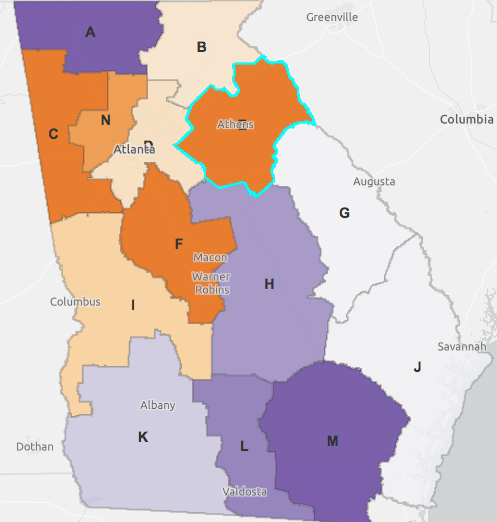

The biggest indicator that local hospitals may be experiencing stress is a sustained low Intensive Care Unit (ICU) bed count for Region E, which includes Clarke and 11 surrounding counties. In the month of July, the data shows ICU bed usage has been at or near the capacity of 70 beds for much of the month. On many days over the past month, the region has had less than five available ICU beds, and on some days there were only one, two or even zero available ICU beds. As recently as Wednesday, both local hospitals were on diversion, meaning they weren’t accepting any new patients except emergency room walk-ins.

“The ICU needs have increased, and they’re holding steady at this high rate. We do see some declines over the weekends, but that’s usually because hospitals just don’t report as regularly over the weekends as they do during the weekdays,” says Amber Schmidke, a public health microbiologist who has been monitoring the pandemic in Georgia.

“I usually pay attention when I see ICU under 20 beds in a region,” she says. “If it’s under 10, I would consider that, of course, even more concerning, but then under five—we know that things happen. You could have a really bad car accident that involves an entire family, and they may all need a bed. You know it’s not just COVID that you worry about when you have ICU bed space that way.”

Hospitals Say They’re Coping

Hospitals in the Athens region are seeing high volumes of patients, but continue to be stable, St. Mary’s Healthcare System Public Relations Manager Mark Ralston told Flagpole in a statement this week. Overall, the statement says, they’re continuing to keep an eye on the situation in their hospitals, but so far have not gotten to a point where they’ve had to reach out further for assistance with state officials.

“The vast majority of patients admitted to St. Mary’s’ three hospitals are not in need of treatment for COVID-19,” according to Ralston. “However, the recent increase in COVID-19 cases in our region is contributing to the higher volumes we are seeing.”

St. Mary’s is working with sister hospitals in Lavonia and Greensboro and other health-care providers, the statement says. Bed capacity is a fluid situation that can change quickly, Ralston adds.

“We have had days where capacity is tight and other days that are not as challenged,” he says. “We deploy our coordinated capacity approach to work together with others to maintain access to care for our community.”

Piedmont Athens Regional Medical Center CEO MIchael Burnett also wrote an op-ed column last week stressing that the hospital has a handle on the situation. He provides details on how the hospital is prepared to handle extra capacity—including plans for additional makeshift ICU bedspace, access to other hospitals in the Piedmont network and access to the new emergency bedspace that recently opened at Piedmont Atlanta’s Marcus Tower.

Health-Care Workers Disagree

Ask doctors and nurses on the front lines, and the rose-colored view that Athens hospital administrators are presenting begins to lose its hue. Local doctors in Clarke County emergency rooms say they’re seeing more and more COVID-19 patients in the last two weeks, and more and more very sick patients of all ages. They’re concerned about UGA students coming back to town and putting further stress on the system.

Lewis Earnest—who underscored that his comments do not represent the views of St. Mary’s—was previously the director of its emergency department and is still an ER doctor there. The pattern of continued and sustained ICU bed shortages is not something that had been a big problem before the pandemic. But the uptick in volume of COVID-19 patients he’s seen in the last two weeks has resulted in reduced ICU bed space and holding patients in the ER for hours as a result, he says.

The number of COVID-19 patients Earnest sees in a shift at the ER varies day-to-day. “Some days it has been 50 percent” of 16–20 patients, he says. “Some days it has been 30 percent.” But he sees the numbers growing. During a shift on the last weekend in July, for example, he says about 70 percent of his patients in the ER had COVID-19, but on a shift last week he said only 20 percent were COVID-19 patients.

“You can definitely feel the ebb and flow of the pandemic in the ER,” Earnest says.” “If you look at the history of epidemics, that’s the typical story. People get scared when someone they know gets it and then they curtail their behavior. When they get tired of the restrictions, behavior starts to loosen, and then the virus roars back.”

Similarly, Brandon Hicks, also an emergency room physician at St. Mary’s, has noticed a surge in COVID-19 patients locally in recent weeks. “I can definitely say that the situation is getting more stressful,” he says. (Hicks, like Earnest, spoke to Flagpole with the caveat that he does not speak for the hospital or his physician group.)

“For the ICU to be completely full is not really that unusual, but for it to be completely full of COVID patients is definitely a first,” he says. “We are seeing more and more COVID patients… Over the past week, I’ve started seeing sicker COVID patients again. The trend is not going well. We’re not trending in the right direction at this point.”

Meanwhile, nurses report even more concerning conditions, both for patients and health-care workers.

“My coworkers and I are concerned about the misleading statements our hospitals have been releasing,” says one Athens ICU nurse who spoke to Flagpole on condition of anonymity. “We have no one to care for these patients [in the ICU].”

ICUs normally use a ratio of one nurse to one patient for patients who are paralyzed, intubated or proned. (Patients on ventilators are usually put into medically induced comas because of the discomfort of having a tube down their throat, and nurses will flip them on their stomachs to make it easier for them breathe.) Now, nurses are stretched to their limits. “We now take two intubated patients, often on paralytics and vasopressors to keep their blood pressure high enough to profuse their organs,” the nurse says.

The situation, the source says, is at a critical juncture, and patient care is suffering. “There are critical care patients waiting in the [emergency department] for days. The emergency department nurses are experts at stabilizing, but aren’t used to caring for critical patients for longer periods, nor do they have the resources.”

While care of COVID-19 patients has gotten better since the onset of the pandemic as doctors and nurses across the country have learned better methods, lack of access to resources now does not bode well for patients. Some are declining ventilators and are candidates for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)—a procedure that circulates blood through an artificial lung and back to the patient’s body—but no facilities in Georgia are accepting ECMO patients.

What’s also concerning, the nurse adds, is that hospitals have not canceled elective surgeries again. The backup plan to create additional ICU space hasn’t been implemented because it would involve training other types of nurses in critical care.

Even with additional ICU space, the nurse contends hospital staff are overtaxed. There are only so many intensivists, or specialized ICU doctors, to go around. And many smaller, rural hospitals don’t have ICUs at all.

“We are tired, and we want to change this narrative,” the nurse says. “It is not OK for the hospitals to promote medical care that we ultimately are unable to provide.” The nurse says they also informed Mayor Kelly Girtz after he released a joint statement with other elected officials seeking to reassure the public.

Nursing Shortage Continues

Nursing shortages in Georgia are nothing new. Georgia officials warned last November that the nursing shortage had reached a crisis level, exacerbated by low wages and retirements outpacing new recruits. In recent months, however, the pandemic has taken an even bigger toll. The Georgia Department of Public Health put out a call in late March for medical and non-medical volunteers and thousands of retired nurses stepped up to the plate. The Georgia Nurses Association expressed concern in April that nurses were being sent to New York to aid with the pandemic when they were likely to be needed in Georgia. Matt Caseman, executive director of the Georgia Nurses Association, said in March that as the virus spreads he worries that nurses would “get burned out” or “there simply wouldn’t be enough nurses on the frontlines.”

Both hospital administrations, however, persist in saying that things are under control.

“We continue our work to maintain a safe environment to meet the care needs of patients with COVID-19 and those with other medical conditions,” says the statement from St. Mary’s. “We understand the risks of delaying care and want patients to feel safe in our facilities. We urge the community to stand with our hospital heroes in the fight against COVID-19 by wearing a mask [#maskupgeorgia], maintaining physical distance, and washing your hands often.”

“Throughout the pandemic, Piedmont Athens has accepted transfers of patients from within its GEMA region—and also from outside of it—and will continue to do so as capacity warrants,” says Burnett, the CEO. “Many of the patients that we accept do not require intensive care unit beds, thanks to the response and hard work of our team at the local and system level. Advances in clinical protocols have improved our ability to treat patients with this truly novel disease—it did not exist nine months ago, but we are learning all the time—and to help them recover. As part of our efforts, we have created additional bed capacity to handle both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients. We are consistently planning for ways to manage capacity—locally and across our system—during this pandemic and otherwise. These fluctuations aren’t new to our team, and we are well-equipped to handle this increase by managing capacity on a daily basis.”

What Happens When Students Return?

Given the state of hospitals and the increase in positive COVID-19 cases in recent weeks, doctors say they are concerned about UGA students coming back for in-person classes in just a little over a week. “I am concerned,” says Hicks. “I’ve thought about this specific idea a lot over the past couple of weeks. It’s very concerning about what could happen when students come back.

“It’s not just the students I’m worried about,” he says, “but it just increases commerce and increases people being out and about at restaurants and bars. You know you have staff at UGA, teachers. You have workers. There’s going to be more people out and about exposed to each other. If we get a surge, I don’t believe that our hospitals will be able to handle it. That’s my opinion.”

To handle such a surge, hospitals would have to get creative by adding more ICU bed space or send patients to Gainesville, Atlanta or Augusta. “I’m definitely concerned that we are heading in that direction,” Hicks says.

Earnest voices further trepidation about UGA students returning. “College students just seem like a recipe for rapid viral propagation,” he says. “These individuals, they’re not in a bubble. They’re interacting with all sorts of people. They don’t all kind of live in a dorm by themselves. They’re living in intergenerational houses. They’re working in businesses with people who are older. They’re eating at restaurants and going to bars, and they’re mixed into our community. I really do fear what’s going to happen.”

For doctors, nurses and other health-care workers in our health-care system, thinking of others could go a long way. Fatigue for many of our health-care workers is really setting in, says Hicks. “I think what contributes to that frustration is knowing that we shouldn’t be in this situation at this point,” he says. “I mean, this country could have done a better job dealing with this.”

Earnest stresses the need for everyone to take the pandemic seriously. “Think about how your actions could affect somebody else, and assume that you are positive,” he says. “I think that the assumption of positivity would go a long way in lessening the spread of the disease. Because I get exposed so much, I assume that I am positive so I have basically no interactions that would put someone else at risk. I think if everyone assumed that they were positive, this disease would end very quickly.”

It’s also important to wear a mask, Earnest says. “It doesn’t even really matter if you’re not worried about yourself. That’s fine. I get it. But worry about the person you could give it to,” he says. “The mask is not protecting you. It’s protecting the other person. I wear my mask for you. You wear your mask for me. It has nothing to do with you being scared. It has to do with being empathetic and thinking of others.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.