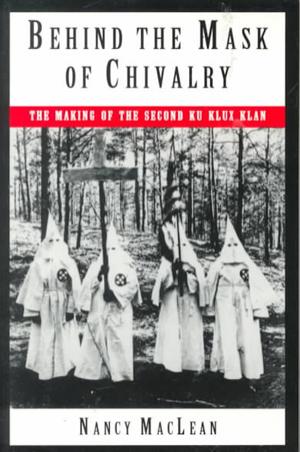

Few books published this year are likely to excite as much interest in Athens as Nancy MacLean’s Behind the Mask of Chivalry, a study of the second and most successful incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Out of the entire South, the detailed records of only one local Klan chapter are available to researchers; MacLean’s work is based largely on those documents. They are the rosters, minutes and correspondence of Klan Number Five of Athens, Ga.

Few books published this year are likely to excite as much interest in Athens as Nancy MacLean’s Behind the Mask of Chivalry, a study of the second and most successful incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Out of the entire South, the detailed records of only one local Klan chapter are available to researchers; MacLean’s work is based largely on those documents. They are the rosters, minutes and correspondence of Klan Number Five of Athens, Ga.

Any Athenian reader who spends the better part of a day’s wages in hopes of toting home a armload of ruined local reputations and spicy anecdotes will be largely disappointed. For legal reasons left vague in her introduction (libel law does not reach beyond the grave), MacLean has used the correct names of Klansmen already identified as such in the public record. For the rest she has used italicized pseudonyms, many of which, including those of three former Athens mayors, can be figured out with minimal effort.

Instead of scandal MacLean offers an ambitious and much needed analysis of who the Klansmen of the ’20s were: their religious, social and economic backgrounds. MacLean also examines the transformations of family, sexual, racial and labor relations taking place during and after the First World War which led millions of white men to enlist in a violent secret organization offering them hope of restoring (or creating) a world of obedient children, compliant wives and quiet subservient African-Americans.

MacLean offer good documentary evidence to refute conventional myths about the Klan, the first being the nature of its membership. Popular folklore, especially among non-Southerners, portrays typical Klansmen as illiterate dirt farmers or factory hands, perhaps under the discreet leadership of some evil aristocrat. The fact is that neither Lickskillet nor Cobbham was much represented in the Athens Klan. The typical Klansmen was a small businessman, skilled craftsman, or low-level white-collar worker. Barbers, grocers, pharmacists, mechanics, clerks and policemen were typical members. The Athens Klan also boasted a few lawyers, two University professors and much of the city’s white Protestant clergy, including the pastor of West End Baptist and the minister of Young Harris Methodist. The Reverend M. B. Miller of the First Christian Church was the Exalted Cyclops, or local leader, of the Athens Klan at its peak of power.

Another misconception addressed by MacLean is the belief that the Klan’s sole obsession was the terrorization of racial and religious minorities. While racist and nativist rhetoric was central to Klan ideology, much of its activity, particularly in Athens, was targeted at policing the social and sexual lives of native-born white protestants. MacLean presents a fascinating and heretofore unwritten episode in Athens history, the Klan led “purity campaigns” of 1922 and 1924 which sought to rid the city of drinking, gambling, and pre- and extra-marital sex. These campaigns included entrapment of bootleggers, brutal floggings of immoral persons and, ultimately, a Klan-dominated city government.

The Athens Klan of 70 years ago had a drearily familiar agenda: fundamentalist Protestant orthodoxy in the schools, featuring anti-evolutionism and a campaign against “alien” influences (Jews and Catholics rather than gays, feminists and Satanists); a moral crusade against the Athens Klan took no issue with white supremacism. The few white Athenians who dared or bothered to speak out against the Klan were from the old Dearing Street aristocracy: David C. Barrow, Andrew Erwin and Lamar Rucker. Their objections were less to the Klan’s goals than to its style: For these heirs of the old planter-professional class the rule of law, represented by themselves, their friends and their kinsmen, was sufficient to insure the traditional paternalistic subordination of blacks, workers and women. They were annoyed and alarmed by the presumptuous shopkeepers and parsons whose heavy-handed methods threatened their carefully constructed pyramid of privilege.

MacLean convincingly demonstrates that, at least in Athens, the second Klan was the vehicle of a middle class that felt itself betrayed from above and beleaguered from beneath. Economic and social changes, especially those accelerated by the World War, threatened the secure social position of native-born white Protestant adult males. The Ku Klux Klan, like the fascist mass movements in Europe, offered this class hope of restoring society to “the way things ought to be.”

MacLean’s book is well-researched and well-argued, but has some weaknesses. She goes into some detail about the Klan-led campaign against Governor Hugh M. Dorsey, who dared to voice some faintly progressive opinions about black Georgians, but nowhere mentions that Dorsey owed his political prominence to his virulent prosecution of Leo Frank, the Jewish factory owner who was lynched after his unjust conviction for the murder of a young female employee. Hugh Dorsey contributed as much as anyone in the state to the atmosphere of white xenophobia which led to the second Klan’s formation. Dorsey was less a persecuted moderate than a political Dr. Frankenstein destroyed by his own monster.

The book’s subtitle, The Making of the Second Ku Klux klan, reaches a little further than the book itself does. MacLean makes it clear that the primary sources for her research are severely restricted—all southern second Klan records were lost, destroyed or hidden except for the Athens documents. MacLean makes excellent use of the available data, but her use of secondary sources, while enlightening in putting the Athens Klan in regional and national perspective, is not sufficient to bridge the gap between her primary data and her basically sound theoretical generalizations. Since MacLean herself expresses some of these reservations in her introduction, my objection really boils down to a quibble over the title.

This book fills a gap left by all previous histories of Athens and should be read by everyone with any interest in local history. It also serves as an excellent reminder that the Klan was not a mob of illiterate, marginal outcasts, but a highly organized society of respectable businessmen and professionals with an interest in “family values,” “patriotism” and “morality.” Athenians of all backgrounds and political stripes would do well to read this fascinating book and ask ourselves how far we have traveled in the past 70 years.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.