As the infrastructure of hospitals and clinics begins to buckle under the growing weight of patients, a national shortage of protective face masks has left health-care workers in a state of panic. Activists are urging people at home to sew and distribute their own fabric face masks to buy time while health-care facilities wait for N95 mask manufacturers to catch up to demand.

To be clear, these fabric masks are not a substitute for N95 respirator masks, which are capable of blocking at least 95% of airborne particles. They can, however, be worn over the N95 masks, thereby extending their life. Additionally, the fabric masks can be distributed to workers who need masks but are not at as much risk of encountering COVID-19, thereby freeing up commercial masks for first responders who critically need them.

Fortunately, seamstresses of local sustainable fashion businesses Community and STATE the Label—along with sewing volunteers of several grassroots circles—have stepped up to their machines to aid local healthcare workers.

After reading about the widespread shortages of protective masks, Community’s owner, Sanni Baumgärtner, answered the call to action. Her downtown boutique specializes in sustainable clothing that utilizes eco-friendly materials and carries its own clothing label, Community Service, that redesigns outdated vintage clothing into attractive, contemporary pieces. Community’s doors have been closed to the public since Mar. 16, and she immediately recognized how the shop’s skills, equipment and space could be put to creative and important re-use.

“It’s a perfect fit, since the fabric masks are washable and reusable and extend the life span of the disposable masks,” says Baumgärtner. “We also work with fabric donations of leftover material, and even got a large pile of scrubs from the hospital that we can use, so we are actually able to continue with our concept of turning used items into something new and useful.”

Currently, Community’s alteration seamstresses Becky Brooks, Shawna Maranville and Allyssa Peace are working alongside redesigners Dulce Brousset and Moana Balogh to crank out as many masks as possible. One of the most significant challenges has been smoothing out the logistics—creating prototypes, sourcing materials, preparing for mass production, organizing a sewing schedule, coordinating with volunteers—a process that would normally take weeks to accomplish but was needed within a matter of days.

“Piedmont Hospital has asked for thousands of masks for all employees and patients who are not on the front line or in surgery but need to be protected, so our main effort right now is to provide them with masks first,” says Baumgärtner. “We also had a local nursing home, a protective child agency, and several nurses reach out independently, that we are connecting directly with some of the volunteers. The need is massive, and we don’t want anyone to have to wait weeks before they can get their masks, since time is of the essence here.”

Community is accepting donations through a GoFundMe campaign to help cover material costs and keep its seamstresses employed, and it has raised enough money to provide over 800 masks so far. Additionally, the shop is providing sewing kits that volunteers can complete at home and drop back off, and anyone interested should contact [email protected].

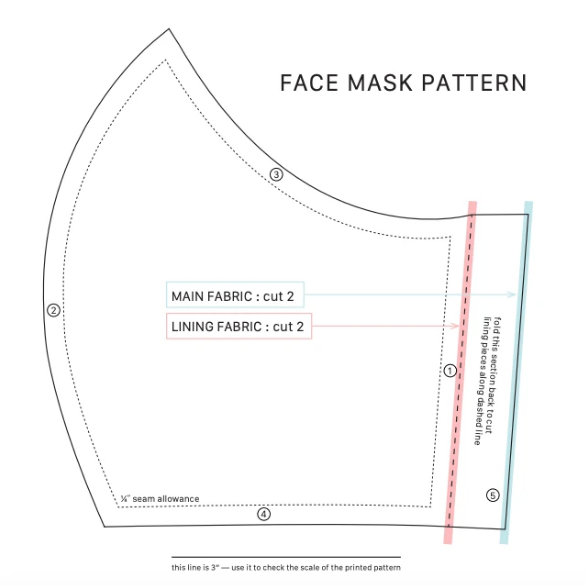

A sewing pattern provided by STATE the Label.

Operating out of a sun-lit studio nestled within an unassuming brick building on Barber Street, STATE the Label is a small-batch clothing brand dedicated to the promotion of natural materials and ethical, transparent labor practices. Founded in 2010 by designer Adrienne Antonson, STATE produces garments that are sewn primarily in-house from responsibly sourced, organic and recycled textiles, many of which are then hand-painted with unique designs for an artistic flourish.

After one of STATE’s seamstresses, Amanda Kapaousouz, learned of medical mask shortages through a friend who works as a nurse in the ER of St. Mary’s Hospital, the studio was also quick to mobilize. Several prototypes were tested before arriving at the design most preferred by the nurses.

“As a sustainable clothing company, we save all of our scrap fabric and small cuts,” says Antonson. “They’re perfect for mask making, and we’ll have made hundreds of masks from leftover fabric and scraps.”

STATE began by donating the cutting time, fabric and elastic for 300 masks, which were divided by seamstresses Tonya Allen, Julie Harris and Kapousouz to complete at home. Additionally, the studio has begun assembling bundles of mask-making materials that can be picked up and sewn by volunteers, then dropped back off for distribution to local health facilities.

“In hard times—and we’ve never had a time as hard as this—it feels good to help,” says Antonson. “This was our little way to tangibly make things better in a small way here in Athens, but to also share what we had learned with the larger world.”

The studio aims to disseminate as many helpful tips as possible and encourages volunteers to link up with one of the several online forums, such as Mask Making for Athens Area Healthcare Workers on Facebook, to streamline production and delivery. A downloadable pattern and step-by-step instructions, complete with photographs, are available online at statethelabel.com. For anyone wishing to support STATE’s efforts from a distance, all online donations will go directly to the seamstresses whose hours have been cut due to the shop’s closure.

Chris Sugiuchi produces face shields using an assembly line of 3D printers in his home.

Taking a different approach to mask making, Chase Street Elementary School STEM teacher Christopher Sugiuchi is 3D printing personal protective equipment for local medical staff. Using an open-source design from Prusa Printers, the face shields combine adjustable headbands with front plates made of clear, laser-cut plastic. Because his initial production was bottlenecked at the 3D printer—with the upper and lower supports taking six hours alone to print—Sugiuchi put out a request for anyone with a 3D printer to step up and assist. Sensing the urgency, a handful of community members pulled together and purchased seven additional 3D printers for Sugiuchi. Currently, Sugiuchi plans to prioritize emergency room staff at Piedmont Athens, and he will later respond to requests from other medical professionals if possible.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.