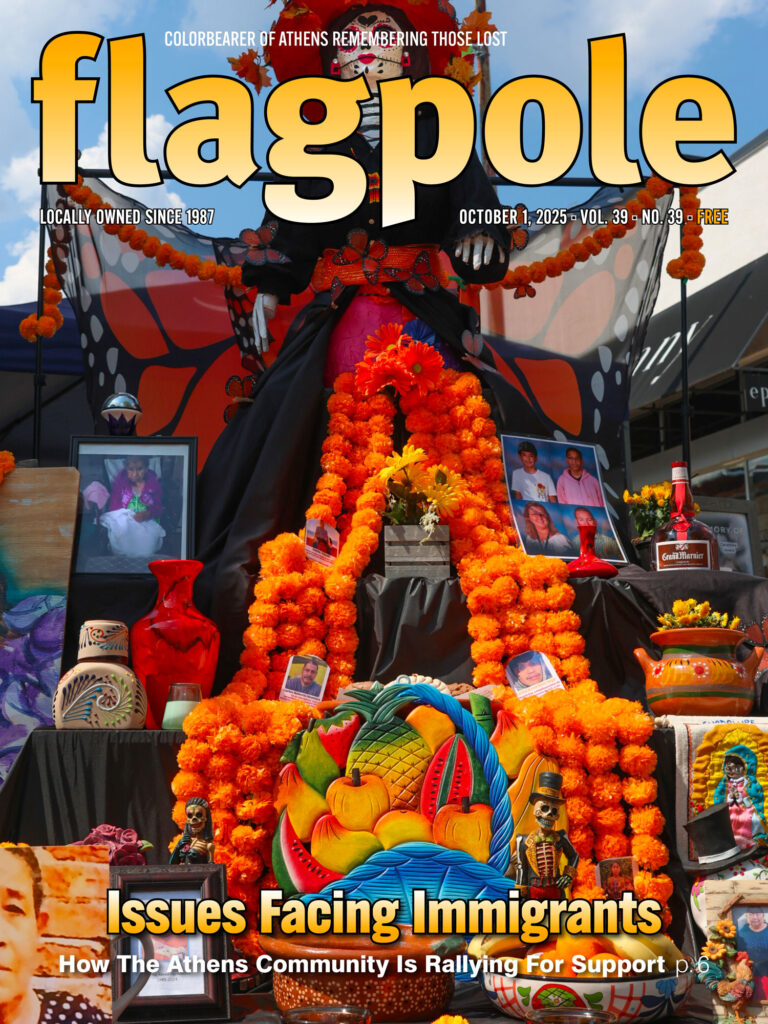

A week and a half ago, joyful crowds filled two blocks of downtown Athens, celebrating the traditions and contributions of the diverse people who make up the local Latino community. Musicians, dancers and speakers took the stage; chefs enticed visitors with their creations; artists and authors showcased their work; kids jumped in a bounce house and worked on crafts. The festival also promoted wellness and community engagement, with tents offering flu shots, resources for college applicants, and voting information.

LatinxFest is a highlight in Athens every year, but in 2025 it also provided an opportunity for participants to support each other in an uncertain time. Over the summer, Georgia ranked fourth in the nation in total Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests for the year, with Latino people bearing much of the impact. Organizers recently canceled Savannah’s annual Hispanic Heritage Parade due to safety concerns.

Living With the Threat of Deportation

About 1.3 million Georgians are foreign-born, which is more than 10% of the state’s population. Athens-Clarke County has a similar proportion of immigrant residents. In 2022, an estimated 347,800 undocumented immigrants lived in Georgia, though less data is available on the city or county level.

Since President Donald Trump took office in January, new policies have also stripped legal status from hundreds of thousands more immigrants. Temporary protected status granted to people from nations facing war, natural disaster or other hardship has been revoked for several countries. So have humanitarian protections for others. Some who are eligible for green cards despite remaining in the U.S. longer than permitted are being arrested at their interviews, as are some asylum-seekers.

In 2019, the Athens-Clarke County Commission passed a “Resolution in Support of Athens Immigrant, Undocumented, and Latinx Community” denouncing white supremacy and promising to “foster a community where individuals and families of all statuses feel safe, are able to prosper and can breathe free.” The Laken Riley murder case brought the resolution into the national spotlight, with some residents accusing Mayor Kelly Girtz of shielding immigrants who commit crimes. But Athens is not actually a “sanctuary city,” as a since-retracted Department of Homeland Security report alleged. “You may not like state or federal immigration law, but we’re compliant with it, and we always have been,” Girtz told Flagpole in June.

Although the resolution does not carry legal weight, many Athenians remain committed to putting its ideals into practice. The Athens Immigrant Rights Coalition (AIRC), formed in 2011, is “a collection of Athens-based groups with a shared goal of asserting justice for Athens area immigrants, regardless of legal status.” As more local individuals and families face arrest, deportation and separation from loved ones, these groups have stepped up to support them, whether with food, legal fees, help with child care or other needs. Volunteers come from diverse backgrounds, and many bring expertise from their professional lives into this work.

The Department of Homeland Security announced in an Aug. 20 press release that ICE had arrested 4,500 undocumented people in Georgia between Jan. 20 and July 31. “367% increase in arrests of illegal aliens in the Peach State compared to Biden,” the report proclaimed. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the number may even be significantly higher. As of Aug. 28, they reported that nearly 2,500 immigrants arrested in Georgia had been deported.

Some of those arrested come from Athens, where distraught family members remain. This spring, a single mother with no previous criminal background who was seeking asylum was called in for a hearing and swiftly deported, leaving her 18-year-old daughter to care for her younger siblings, according to immigrants’ rights activists. Though friends and community groups have provided food and financial assistance, the teenaged daughter left high school and is focused on finding a job that can support the family she now heads. In August, a grandfather and Sunday school teacher was detained by ICE at his regular check-in with immigration officials. Some families are choosing to “self deport” and return to their home countries, or move to states they hope will be safer. Some leave without telling any of their friends or neighbors.

“They say, ‘This isn’t living,’” Teter, an AIRC member, says through an interpreter. “This is no life to live in this kind of fear… We see people in our community selling their things, selling their houses.” (Teter asked to be identified only by her nickname.) She also points out that for every deportation reported, family members may follow so that they can stay together, meaning that even more people are leaving the country than early statistics likely reflect.

About half of the ICE arrests in Georgia occur in local jails, the AJC reported. The Georgia Criminal Alien Track and Report Act of 2024 (HB 1105) requires sheriffs and jails to report on the immigration status of everyone incarcerated. The bill also allows law enforcement to detain anyone they suspect of being in the U.S. illegally. As of September, 25 ICE detainers had been issued to the Athens-Clarke County jail this year, keeping inmates incarcerated so ICE can take them into custody, even if they would otherwise be released. (Eighteen of those people were picked up by ICE.) An Athens man who was arrested for jaywalking was picked up by ICE from the Cobb County jail and is now being held in Stewart Detention Center, where he is sleeping on the floor due to overcrowding. A diabetic who has had several toes amputated and needs further amputations, he was still waiting to receive his prescription medications three days after intake.

Clarke County Sheriff John Q. Williams says that his office does not target people “based on how they look or what language they’re speaking,” and that racial profiling violates people’s rights. “We’re focused on keeping our community safe and protecting everyone’s Constitutional rights who are in the United States,” he says. “We’re focused on safety for everyone.” But in the context of the larger system that criminalizes their presence, undocumented people may find it hard to trust law enforcement, and may avoid interacting with officers even when they’ve been the victims of crime.

Sujata Winfield, an immigration attorney in Athens, says that she has been fielding calls from more prospective clients than she can take on. And as a vast backlog of immigration cases builds, some of her clients may be incarcerated for the better part of a year before receiving a hearing. When a case comes to court, she says it may be rushed through, or a judge may make a ruling without allowing a defendant’s lawyer to argue the case. Winfield says that the government is routinely violating people’s rights to due process and a free and fair trial as the administration pushes to remove as many people as fast as possible and to involve agencies beyond ICE. “Nothing is really safe anymore,” she says. Still, as a lawyer, “you have your cases and you put your efforts into trying to keep people from being deported.”

Community Support

Traffic stops have been a major source of immigration arrests. Being stopped for a broken taillight or other minor alleged violations can upend a person’s entire life. Undocumented people can’t apply for driver’s licenses in Georgia, so driving without a license or with a suspended license is often an issue. Undocumented passengers aren’t safe from having their immigration status checked, either. Because of these risks, many undocumented people are understandably afraid to drive, especially to court dates. They may also postpone important medical appointments because of transportation concerns.

To address these challenges, AIRC has a rideshare program in which volunteers with current licenses, insurance and registration drive at-risk people to their engagements. The group also includes a team of volunteer legal observers who respond to reports of ICE and other law enforcement activity affecting immigrants and attempt to document and/or deescalate the situation. These volunteers kept watch during LatinxFest, which was celebrated without incident.

Dignidad Inmigrante en Athens, one of the groups that make up AIRC, also managed to get the mobile unit of the Mexican Consulate in Atlanta to spend several weeks in Athens, helping Mexican citizens get their passports and copies of legal documents, such as birth certificates. People came to Athens from all over Georgia and even Tennessee and Alabama for those services.

Teter worries about the mental toll on targeted communities, especially the children. One little boy she knows told his parents in tears that he didn’t want them to be eaten by alligators—he had learned of the infamous detention center in Florida called “Alligator Alcatraz.” A mother herself, she knows that kids may also keep emotional pain inside. When she can, she organizes informal art therapy sessions in neighborhoods where many undocumented or mixed-status families live, so that kids can forget their worries for a while and express themselves. She has also helped coordinate dance and yoga sessions for all ages to relieve stress.

No one knows exactly how many undocumented students there are in Athens-Clarke County or in Georgia. Under current law, public schools may not request proof of citizenship. (Republican legislators in several states have introduced bills they hope will force the Supreme Court to revisit that law.) Athens-Clarke County is a diverse school district, with a large number of students enrolled in ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages). Many kids are part of mixed-status families; they may have been born in the U.S. but have parents or older siblings who are undocumented.

Lori Garrett-Hatfield has been teaching ESOL in Athens elementary schools for more than 20 years and has chaired AIRC’s K-12 committee since 2017. She too has seen firsthand how kids are affected when a parent is arrested or deported. Young children are exhibiting PTSD, anger, depression and anxiety, she says. Even if their parents have not been taken, “they know that mom and dad are scared, but they don’t know why.” (Garrett-Hatfield clarifies that she does not speak as a representative of CCSD.)

Schools had previously been designated as “sensitive” or “protected” locations by U.S. immigration enforcement, but in January, the Trump administration removed that policy, inciting widespread fear of ICE raids at schools across the country. Dips in attendance have been observed throughout the U.S. since then. Garrett-Hatfield says that in August, families and teachers became concerned about gatherings like open houses for parents or holiday celebrations, especially during Hispanic Heritage Month. CCSD policy requires a court order—not the administrative warrants commonly used by ICE—for agents to enter a school.

AIRC will hold a forum this month where teachers can ask questions of an immigration attorney and a law enforcement attorney to understand what they can and can’t do to protect students. The group provides resources to families in the district who are in need, and encourages undocumented parents to make family plans and have designated guardians for their children in case they are detained. It also works to educate teachers about how the deportation push is affecting students.

Despite her distress at the present situation, Garrett-Hatfield has been heartened by how many people want to help. “Athens is a really unique community of caring people who want to do right by their neighbors,” she says. “It helps me smile on days when it’s not so easy.”

Some of the AIRC’s meetings have brought as many as 100 attendees. In August they met in a church’s fellowship hall, a room with gray carpet and colorful artwork and a long table at the back where women served tacos. Committee members reported on the past month’s accomplishments and challenges—rides given, scholarships awarded, financial assistance provided. An Athens salon had raised money; so had a yoga studio. Someone won a contest and donated their prize money. The Interfaith Sanctuary Coalition broke off to discuss the march that would be held on Sept. 21 (see p. 5). Others discussed communications to policymakers. Despite the difficult circumstances bringing them together, people seemed to be in good spirits.

Teter and Alys Willman, an AIRC organizer, say that every week, what is needed changes, and what it means to be in community changes. Teter says that while it’s important to acknowledge the suffering and pain many immigrants and their loved ones are going through, she does not want that to overshadow the amazing lives they have made, and the love and care that has poured out in response. Throughout the day at LatinxFest, she says, people expressed gratitude that they are still able to gather, knowing that elsewhere others may not feel free to do so. “It’s healing for us to be together,” she says.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.