The exhibition “Beyond the Medici: The Haukohl Family Collection” is currently on view at the Georgia Museum of Art through May 18. Mark Fehrs Haukohl, president of a multinational family investment office based in Houston, organized the show from his family’s private collection of Florentine Baroque art, the largest outside of Italy. He wrote, “In some small way… the Haukohls would like to open a window to illustrate what Florence was like in the 17th century at the Medici Court.”

After a tour in Europe, the exhibition is visiting academic museums in the United States. According to Haukohl, “The important scholarship and superior humanities programs offered at the University of Georgia immediately drew us to include the Georgia Museum of Art in the American tour of the Medici Collection. We look forward to sharing with the students and broad communities of Georgia the joy of the Baroque.”

Nelda Damiano, the museum’s Pierre Daura Curator of European Art and the curator in charge of the exhibition while it is in Athens, explained its attraction: “We don’t have this kind of material at the museum. We don’t have Baroque art from Florence… Everyone talks about Rome when they think of Baroque. Everyone thinks that after Michelangelo died, Florence died, too, that nothing happened, but they did move forward.”

During the High Renaissance, Florence was an important center for the arts, fueled by the powerful Medici family of bankers, politicians and Vatican popes who served as patrons for many artists. However, the Medici continued to commission art during the Baroque era that followed the Renaissance. The Baroque dates roughly from the 17th through the mid-18th century, and the style is marked by drama, high contrast, exaggerated movement and heightened emotions. Many of the paintings in the exhibition, though, show the continued influence of Renaissance art and represent a less intense expression of the Baroque.

The works of art in “Beyond the Medici” primarily depict religious subjects. Christian saints and their traditional attributes (Saint Mark with his lion, Saint Catherine with her spike wheel) abound. One gallery highlights allegorical images and Greco-Roman gods, and another focuses on portraits, including Flemish artist Justus Suttermans’ “Portrait of Giovan Carlo de’ Medici” from before 1644. Suttermans depicts the well-known collector and arts patron—and second son of the Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici and Maria Magdalena of Austria—in glorious military dress.

Damiano finds “Judith Beheading Holofernes” by Onorio Marinari especially compelling. “Judith and Holofernes, just like David and Goliath, was a topic that was dear to Florentines because it’s the little guy winning against the big guy. It’s a popular image in Florentine art starting in 1500,” said Damiano.

While Caravaggio’s gruesome interpretation of the story is more familiar, Damiano finds this Judith “very elegant,” “so serene and poised,” and, by showing her in fancy garments, a closer realization of the Biblical text. Damiano also points out that in “Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene” by Felice Ficherelli, another gory story, the focus is on the nude figure rather than the arrow wounds. “I like how a religious subject became an excuse for artists to work on something they were interested in.”

Other particularly curious works include a small-scale painting of “St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness” by Giovanni Battista Vanni from the early 1620s, painted in oil on a semi-transparent sheet of quartz backed by slate. This unusual background creates the illusion of clouds in a blue sky and attests to the fact that unconventional materials were popular in Florence at the time.

Another work, “Virgin and Child” by Mario Balassi from 1660, depicts a lavishly robed Madonna. The artist, who had fallen on hard times, reused an older panel, painting over an earlier Madonna and child, to save money.

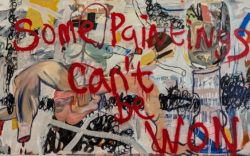

Damiano hopes visitors take away “a visual experience.” She believes that “a lot of these works are showstoppers, in terms of the paintings themselves,” adding that the frames are equally as attention grabbing. “The collector is a lover of frames. He’s really been mindful of framing these works.” A few frames are magnificent period objects, while most were made recently. The catalog explains, “in his effort to recreate the baroque splendour of the Medici court, Sir Mark did not simply imitate existing antique models, however, but even commissioned frames to be made specifically for his paintings by highly skilled craftsmen.” The lively Harlequin painting, on this week’s cover of Flagpole, has a deeply carved and gilded custom frame featuring playful putti and theater masks.

Damiano also wants visitors to leave the exhibition with an understanding that Florence was “still an artistic hub” during the Baroque, and that the Medici were continuing to support the arts there. “I hope that people realize that Florence was still thriving. They are not household names, these artists, definitely not, but it’s a learning experience,” said Damiano. This exhibition is a rare opportunity to enjoy an overlooked area of Italian art history.

The Georgia Museum of Art will host numerous events related to the exhibition, including a talk by Paola De Santo, associate professor of Italian at the University of Georgia, on Mar. 26 and an in-depth discussion of Pietro Dandini’s painting “Esther Before Ahasuerus” on Apr. 16.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.