Though incarcerated individuals make up a significant portion of the U.S. population, they are one of the most underserved and least pursued audiences by arts organizations. Recreational and rehabilitative, the effects of arts programming in prison settings can be transformative: improved quality of life, emotional regulation, coping skills, social bonds and educational outcomes. Currently on view at the Georgia Museum of Art, “Art is a form of freedom” presents a collection of works that were selected by incarcerated individuals at Whitworth Women’s Facility, a prison in North Georgia, through a collaborative, interinstitutional project.

Common Good Atlanta provides people who are incarcerated or formerly incarcerated with access to higher education by connecting Georgia’s colleges with Georgia’s prison classrooms. Since its founding in 2010, CGA has grown into a network of over 60 faculty members teaching over 35 courses across four different prisons. Students can choose their own adventure through a variety of topics, or seek college accreditation through the Clemente Course in the Humanities, a well-rounded curriculum of core disciplines such as critical thinking and writing, literature, U.S. history, philosophy and art history.

Callan Steinmann, curator of education at the museum, began working closely with Caroline Young, a lecturer of English at UGA and site director for the Common Good Atlanta program, in 2021. Over the course of several semesters, UGA students enrolled in Young’s service-learning English course “Writing for Social Justice: The Prison Writing Project” were tasked with designing a way to create a museum experience for the students at Whitworth. After reviewing the museum’s permanent collection, the class created art kits that included high-quality reproductions of over 140 artworks, biographical information, historical context and questions to prompt reflections. These art kits were then integrated into Clemente classes taught by Young and Athens artist and musician Don Chambers.

After reflecting on the artworks through discussion, creative writing and art making, the women of Whitworth narrowed down a selection of works that felt personally meaningful to display in the exhibition. Representing a wide range of styles and time periods, the exhibition collectively ties together themes of identity, motherhood, home, incarceration and freedom. The women additionally wrote poetry and prose in response to the pieces, and these writings can be found alongside the artwork on wall placards and in a publication available in the gallery.

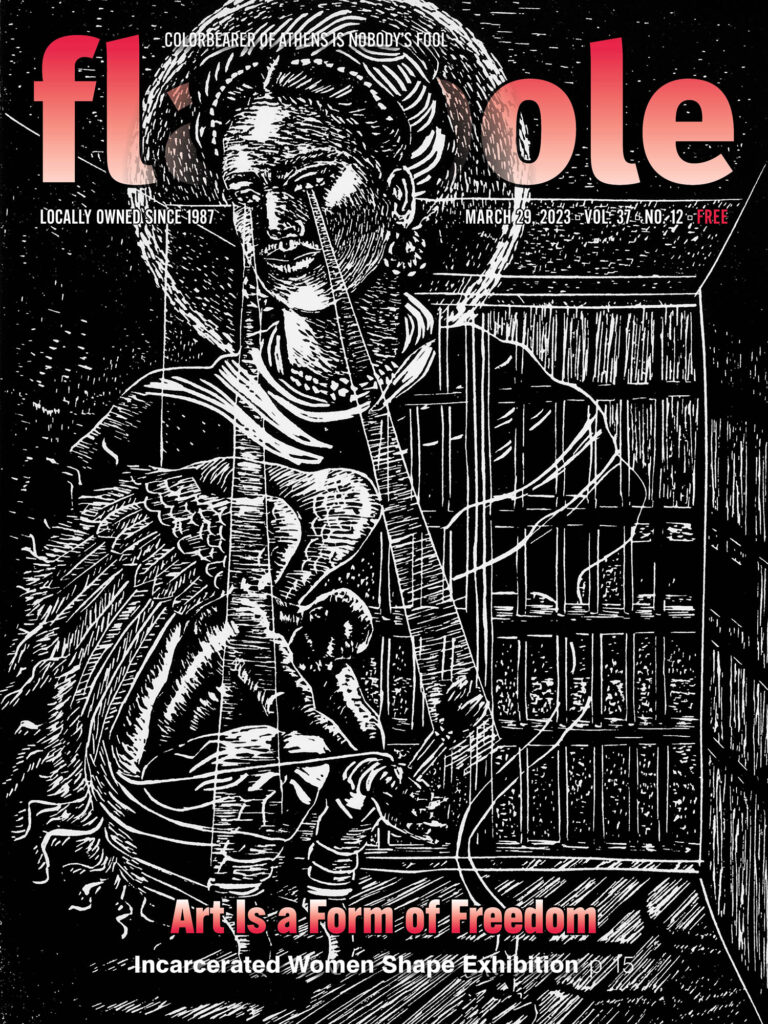

San Francisco Bay Area artist Ronnie Goodman, whose linocut “Broken Wings” appears on the cover of Flagpole this week, is someone whose story illustrates the potential art has to change an incarcerated person’s path. While serving a sentence for burglary at San Quentin Prison, he discovered his love and talent for portrait drawing through an Arts in Corrections Program taught by Art Hazelwood. Though he returned to living on the streets after his release, he continued creating powerful artwork by obtaining materials through a homeless resource center and using a friend’s studio space. The artwork of both Goodman and Hazelwood was later presented together at the Georgia Museum of Art in an exhibition focused on art’s ability to confront present-day realities such as homelessness, poverty, violence and corruption.

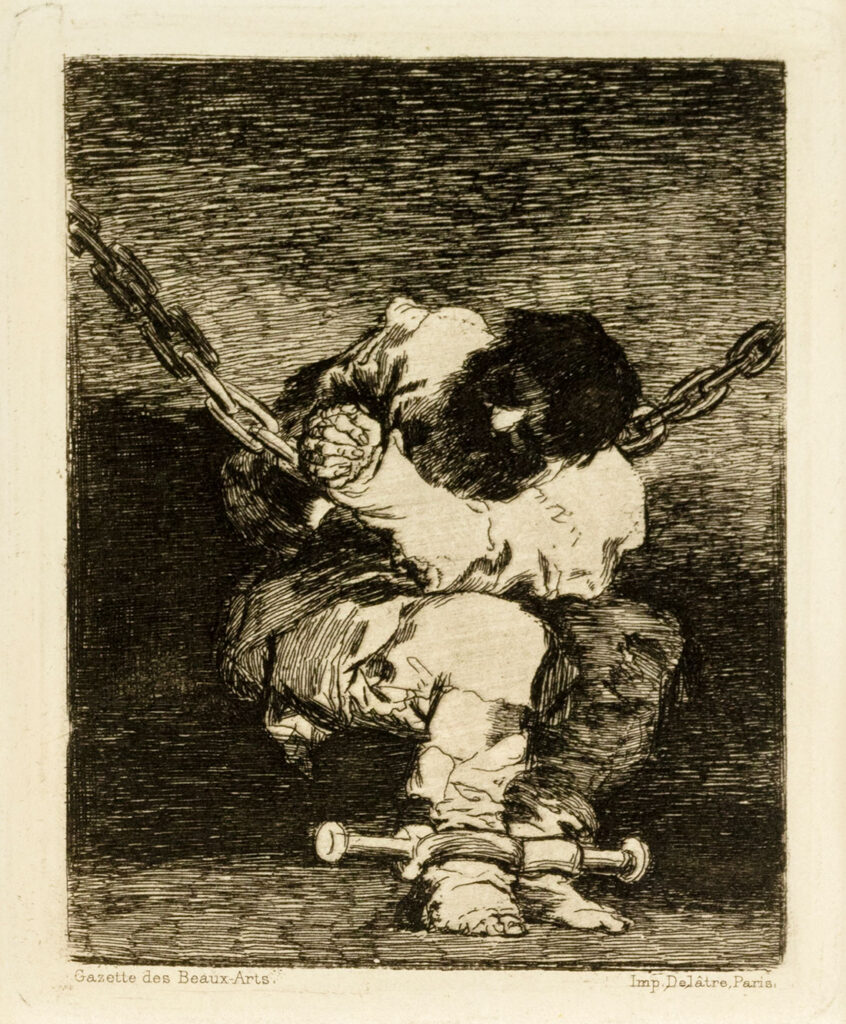

Spanish romantic painter and printmaker Francisco Goya (of “Saturn Devouring His Son” fame) similarly touches on the agony of incarceration through his miniature etching “Tan Barbara la Seguridad” (“The Custody Is as Barbarous as the Crime”). Signs of suffering and grief also flash across the faces within Pierre Bourdelle’s lithograph “Prisoners.”

Balancing those sorrowful yet relatable works are others that feel hopeful and earnest. Faith Ringgold’s print “Coming to Jones Road: Under a Blood Red Sky #8” depicts two embraced silhouettes walking down a yellow road towards a house off in the distance. A story around the image’s border reads “Aunt Emmy could be in two places at the same time and Uncle Tate could vanish in a flash and turn up in the same way. One day they just up an walk to freedom an nobody see ‘em go.” To the right, Dox Thrash’s graphite, ink and gouache scene “Monday Morning Wash” depicts a welcoming and comforting domestic scene. John Biggers’ “Star Gazers,” Herman “Kofi” Bailey’s “Mother and Child” and Michael Ellison’s “Looking for a Friend” are each bittersweet reminders of all the friends, children and family members missing their loved ones who are living behind bars.

“Art Is a Form of Freedom” will remain on view through July 2. Steinmann will offer a curator talk on Wednesday, Mar. 29 at 2 p.m. Alumni from the Common Good Atlanta education program will perform poetry and prose from the work of incarcerated writers at Whitworth during a program called “Can you see me? Here, in this place?” which includes a panel discussion on Apr. 18 at 5:30 p.m. Art & Krimes by Krimes, a documentary exploring the life and secret creative process of incarcerated artist Jesse Krimes, will be screened on Apr. 27 at 7 p.m. Additional related events include a teen studio on Apr. 27 rom 5:30–8 p.m., a creative aging art workshop geared towards ages 55 and up on May 16 at 10 a.m., and an Art + Wellness Studio on June 11 at 2 p.m. Visit georgiamuseum.org for details.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.