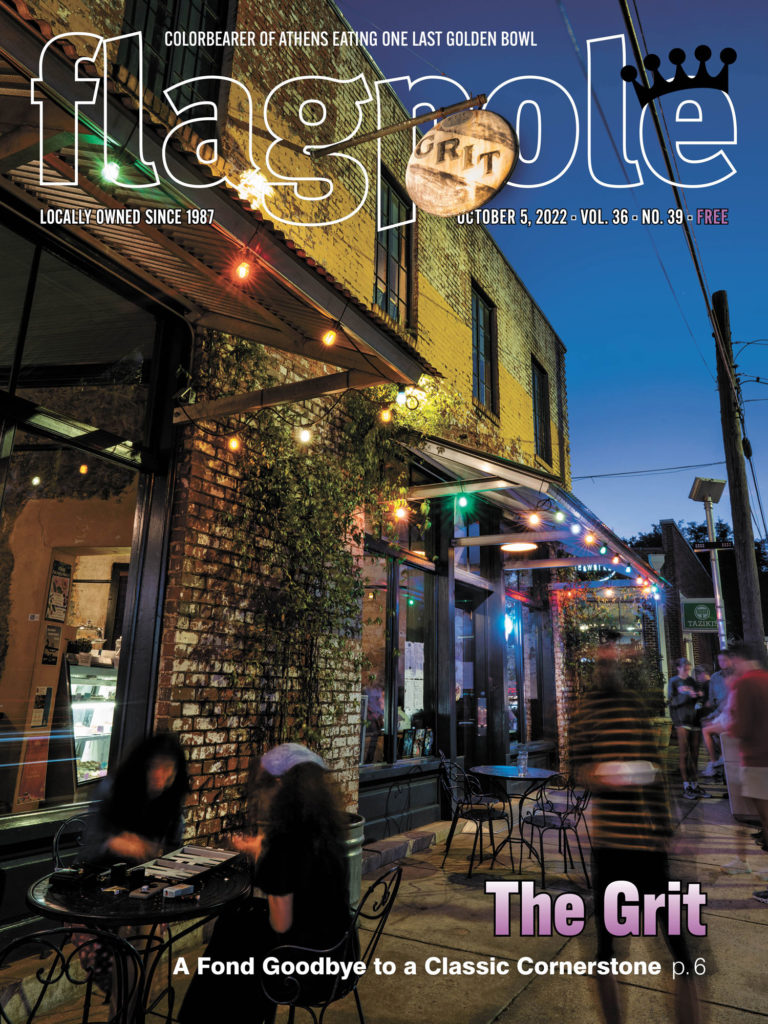

Athens is losing more than just the city’s only locally owned vegetarian restaurant when The Grit shuts its doors for the final time this week: Our town is losing a piece of its beating heart.

“It was the soul of Athens, really,” an irreplaceable essential element, said a longtime faithful Grit patron, Athens artist and retired University of Georgia art professor Judy McWillie.

The Prince Avenue restaurant announced the imminent closing Sept. 22 in a social media post addressed to its customers, noting accurately that The Grit has been “the cornerstone for vegan/vegetarian food in Athens” for more than 30 years. “Unfortunately things have changed due to the pandemic and we’ve had to reevaluate our business goals. So, it is with heavy hearts but with a hopeful eye on the future that we announce that we are closing our doors at the end of the evening service on Friday, October 7th, 2022,” read the post in part.

Word traveled fast and far, to widespread dismay. For at least a while, business has picked up considerably as not only Athenians but former customers who’ve moved off to Atlanta and other places headed back to the Grit for one, two or three last meals at the famous eatery.

“If anyone can make this not happen, I’ll mow your lawn, cut your hair and paint your home, all while I give you a key to the city,” tweeted Athens-Clarke County Mayor Kelly Girtz, a vegetarian.

There was a run on copies of the famous The Grit Cookbook, and online sellers jacked up their prices. The lowest price for a copy on ABE books Thursday afternoon was $72.56, plus $5.55 shipping; on Amazon, one copy was available, at $38.98 plus shipping.

The Grit was born back in 1986—not coincidentally as the Athens music scene had exploded into national consciousness—when two young Athens women, Jennifer Hartley and Melanie Haner Reynolds, decided to start a combination coffee shop and art gallery at the old train station on Hoyt Street.

In 1990, the restaurant moved to Prince Avenue, run off from the station by frat boy violence emanating from a bar that was also a station tenant, said former part-owner Jenna Schuh. Schuh bought into the business in 1988 after the founders decided to move on, leaving it in the hands of first Brenda Mills, who subsequently sold her half to Schuh, and Jessica Greene, the sole owner since 1995, when Schuh fell in love, got married and moved away (but is now back in Athens). R.E.M. frontman and Grit patron Michael Stipe agreed to rent them a building he owned on Prince Avenue at that time, when “we decided to make it a full-scale restaurant,” Schuh said.

The Grit’s fame rests first on its excellent, often simple but also often ground-breaking edibles, like its Grit Staple—pinto beans, onions and cheese served over brown rice, seasoned and topped with sauteed vegetables—and Schuh’s invention, the Golden Bowl. The dish won an award from Vegetarian Times when someone there tasted the revolutionary recipe combining tofu, soy sauce, vegetable oil and nutritional yeast with other ingredients, topped with yeast gravy or cheese and sauteed vegetables. Those two remain among the most popular dishes, along with others, such as the delectable black bean chili and a case always full of cakes and pies, all baked in-house, said Grit server Riley Obert.

“What I liked about it, it’s not a health food restaurant; it’s a vegetarian restaurant,” said Flagpole food writer Hillary Brown.

The food at the Grit was, is, like nothing you could find anywhere else, said McWillie. “They had Middle Eastern, Mexican, American food; they had everything, and not only that, it was the best in town,” she said. “There’s no other food like it. It was vegetarian, but it was world food, too.”

The clientele was diverse: straight-laced country people from Elbert County as well as Athens hipsters. But The Grit was also unique in its connection to the Athens cultural scene. Employees tended to be aspiring artists, musicians and other creatives, encouraged by owners like Greene and her late husband Ted Hafer, beloved by many of the employees, who died in 2007.

“He was one of the best human beings I ever met,” said former manager Patrick Fraser. “He’d show up at your house at 9 o’clock if you were supposed to be there at 8:30.” But he wouldn’t fire you.

From time to time, musicians working at The Grit—Gazelle Amber Valentine of Jucifer and many others—would go off on band tours, for weeks or months, but when they came back, they’d still have a job, he said.

“We’ve always been staffed by artists and musicians,” said longtime Grit manager Jay Toddy.

One Grit worker who’s a professional clown recently returned from a European tour. McWillie noted former Grit servers include Jason Thrasher, who began building a career in photography in his time there. Bands were born there; connections happened.

“We nicknamed it the ‘quantum junction,’” McWillie said. “People would come in and wind up collaborating on projects, because of that incredible mix of people and the food.”

“They really provided more of a family,” Fraser said. “That place did really breed a quality of character and people attempting to do something with themselves.”

There was always an art exhibit on the walls—sometimes bad art, but also sometimes world class, like the folk artist R. A. Miller. One piece still hanging in the restaurant, “God Love The Grit,” belongs in the Georgia Museum of Art, said McWillie, a folk art authority.

Such a nurturing environment helped The Grit keep a loyal workforce, some of whom have worked there for decades. “All my friends worked there,” said Katie Gasperac, a co-owner of Normaltown’s Hi-Lo Lounge, explaining why she poured so much of her life into The Grit from 2001–2008. “Every working day was a day with all your best friends. What’s the point of having a day off when all your friends were at work?”

“Great atmosphere, great people,” said baker Vernon Thornsberry, a Grit veteran of two decades who’s earned respect as an artist in that time. “It’s sad, because it’s something you love, that was part of you. It’s like a big old hunk taken out of you because of the passion you have for it.”

Primarily take-out restaurants have generally prospered over the past couple of years, but the COVID era has been tough for primarily sit-down restaurants like The Grit, said Athens Downtown Development Authority co-director David Lynn. Even in the best of times, restaurants survive on thin margins, and that’s been especially true of the labor-intensive Grit, whose owners have seen nurturing their community and workers as much a part of their mission as feeding hungry diners.

“We’ve always struggled to make it work,” Toddy said.

Now the struggles have intensified here in the time of COVID. Inflation is driving up costs, they’ve seen employee turnover like never before, and of course people have been staying at home. And many restaurants nowadays have vegetarian options, Toddy noted—that’s good for the planet, though maybe not for The Grit, he said.

This summer was unusually slow not only for The Grit but other Athens restaurants, Toddy said. “Jessica was holding on, holding on, really feeling like it was going to be a big fall,” he said. But that didn’t happen.

McWillie, among others, hopes The Grit will survive, in spirit if not as an actual entity. “It’s going to be a terrible blow to the community,” she said. “It provided cohesion.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.