Long before bulldogs roamed the earth, the land now recognized as Athens and its surrounding regions had been occupied and cultivated by Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek) and Yuchi tribes for thousands of years. Through a series of treaties and the Indian Removal Act of 1830, these tribes were stripped of all land ownership and forced to walk thousands of miles along the “Trail of Tears” to federal territory west of the Mississippi River. Many did not survive, but those who did put down new roots to ensure their future generations would not vanish.

Currently on view at the Georgia Museum of Art through Jan. 30, “Collective Impressions: Modern Native American Printmakers” offers a chronological overview of influential Indigenous artists active during the second half of the 20th century. Paper as the chosen medium subverts its complicated past as the material used by Westerners to control and relocate indigenous tribes. Offering a means of social commentary and experimentation, printmaking’s collaborative and communal nature resonates with principles of reciprocity and intergenerational passing of artistic knowledge.

November is National Native American Heritage Month, a presidential proclamation to honor and celebrate the unique cultures, ancestry, traditions and contributions of Indigenous people. This week also coincides with the 400th anniversary of the 1621 harvest feast between the Plymouth colonists and Wampanoag tribe for which today’s Thanksgiving is modeled after. The romanticized, white-washed storybook narrative of the holiday’s origins fails to recognize the subsequent slow-burning genocide characterized by fragile alliances, rampant disease, brutal massacres, forced enslavement and utter dispossession—of homeland, language, identity, autonomy—experienced by an overwhelming majority of Natives.

“Collective Impressions” asserts that Native American history is American history, and several artworks address relevant ideas pertaining to history, memory, belonging and exile. Erasure of Native narratives leads to the invisibility of Native people, which is why it’s so important for exhibitions such as this one to provide a platform for these diverse voices. By including artists of different tribes from varying geographical regions, each with their own distinctive style and approach to printmaking, “Collective Impressions” helps break down stereotypes and demonstrates the rich cultural impact these tribes continue to have on contemporary U.S. society.

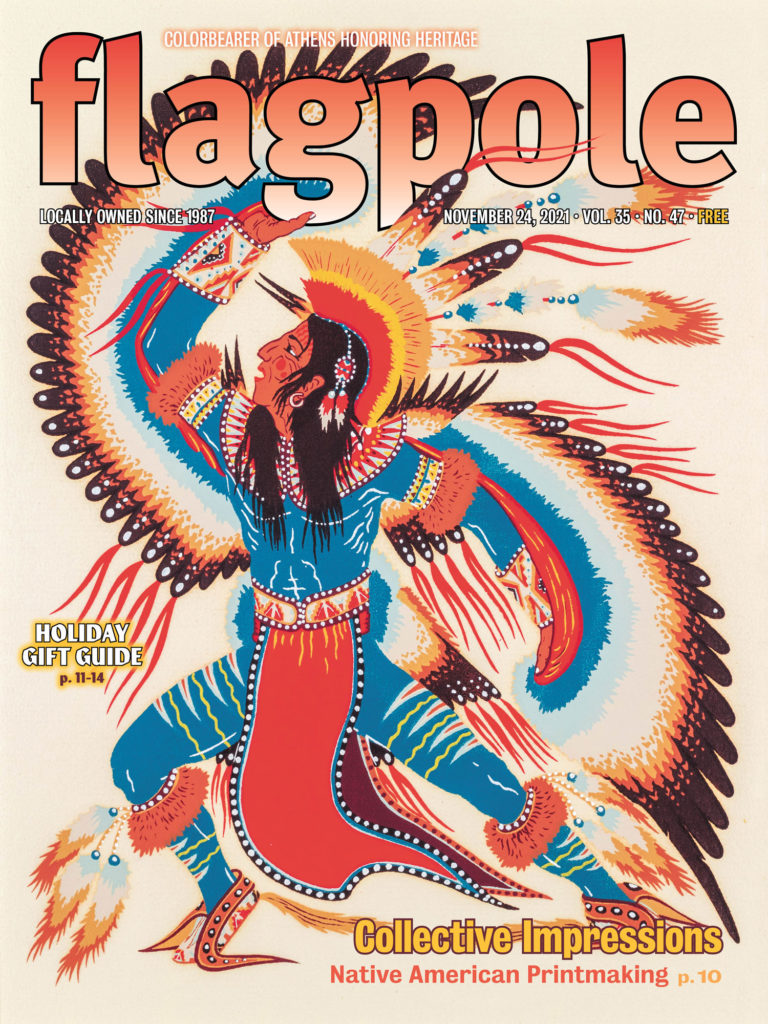

On the cover of Flagpole this week, “Eagle Dancer” by Woody Crumbo (Muscogee/Potawatomi) depicts a sacred rite performed to request divine intervention. This ceremonial dance was banned by authorities in 1883, thereby pushing these performances underground as acts of resistance. Crumbo was introduced to printmaking at the University of Oklahoma School of Art, which became a center of training, production and exhibition for Native artists.

Like T.C. Cannon (Caddo/Kiowa) and Fritz Scholder (Luiseño), Harry Fonseca (Maidu) uses humor to confront myths about Native American communities. His lithograph, “Rose and the Res Sisters,” depicts an anthropomorphic coyote, a popular trickster who plays a role in Maidu origin stories and reoccurs across the folklore of several other tribes. Serenading viewers in a pink rose-printed dress, microphone clutched by long gloved paws, she challenges viewers’ perceptions of time, performance and tradition.

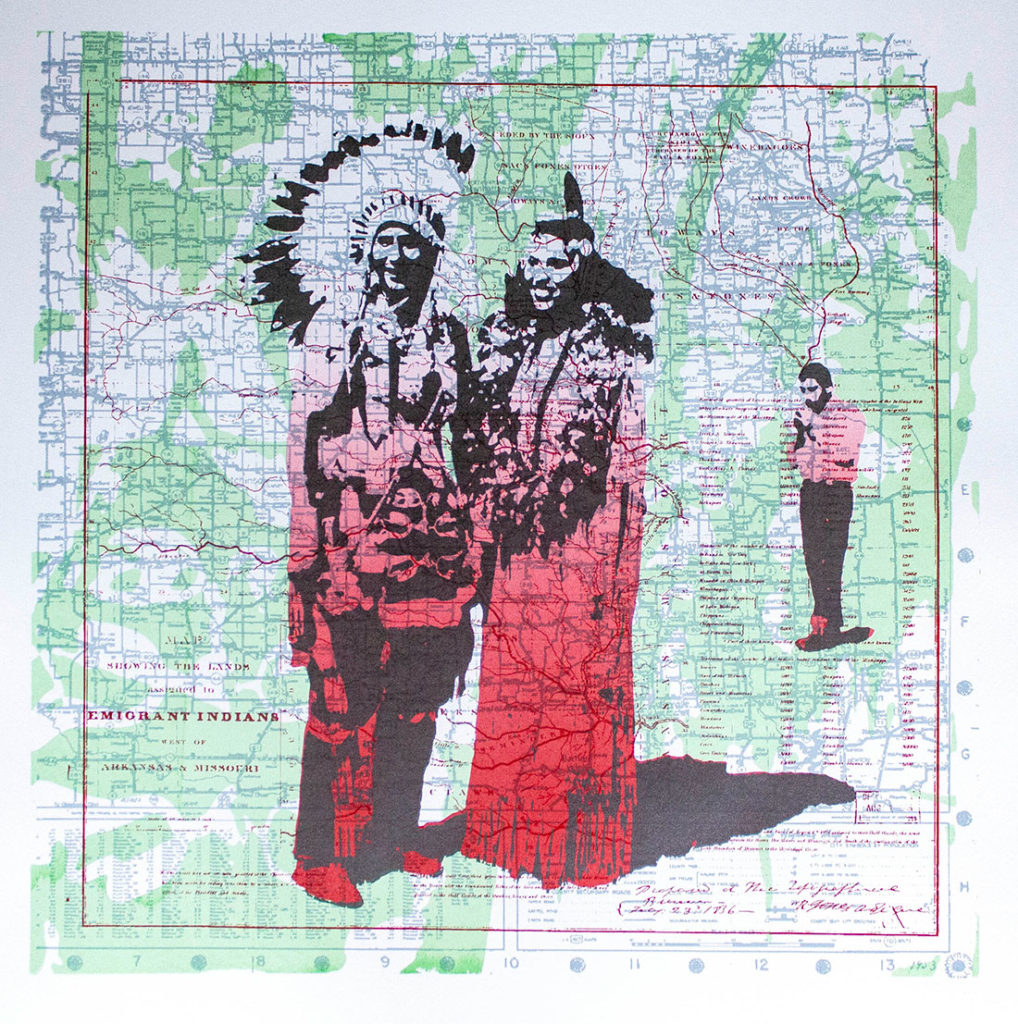

Bobby C. Martin’s (Muscogee) screenprint, “Emigrant Indians #1,” layers two separate maps of Kansas: a map of tribal peoples removed to the region from 1836 and a roadmap from 1950. In the center, a snapshot from the early 1950s depicts a homecoming king and queen wearing full regalia. The piece contemplates emigration, dispossession of land and finding a sense of home.

The exhibition highlights several of the leading communities and institutions that have been central to elevating printmaking as a medium. On Thursday, Jan. 20 at 5:30 p.m., painter Yatika Starr Fields (Osage, Cherokee, Creek) will offer a gallery talk on his body of work, focusing on a series of lithographs and monotypes produced during a residency at Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts. Located on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in the foothills of Oregon’s Blue Mountains, Crow’s Shadow is a nonprofit dedicated to providing a creative conduit for educational, social and economic opportunities for Native Americans through artistic development.

In conjunction with the exhibition, UGA’s creative writing program invited six graduate students—Chelsea L. Cobb, Nathan Dixon, Nathan Gehoski, Aviva Kasowski, Mike McClelland and Hannah V. Warren—to record poems from When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry. Published in 2020, this landmark anthology was edited by U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo (Muscogee), UGA professor LeAnne Howe (Choctaw) and scholar Jennifer Foerster (Muscogee). Accessible by phone, each recording is paired with a different print to highlight the interrelationships among oral, written and visual traditions in Indigenous culture.

Chartered in 1785, the University of Georgia delayed its opening until 1801 due to the Oconee War, a violent conflict between settlers and the Creek over access to the resource-rich Oconee River. Though a few of UGA’s departments have released land acknowledgements in recent years to recognize the ancestral homelands on which the campus now stands, the university’s administration has no formal requirement.

The museum’s own land acknowledgement states “We value the enduring influence of the vibrant, diverse and contemporary cultures of Indigenous peoples. We are conscious of the role in colonization that museums have played. We choose to hold ourselves accountable to appropriate conversation, representation, connection and education to facilitate a space of measurable change.”

Museums have always played critical roles in preserving, promoting and representing Native American culture—but haven’t always gotten it right. With several artists representing the Muscogee and Cherokee Nations, such as Jerry Ingram, America Meredith, Virginia A. Stroud, Kay WalkingStick, Richard Ray Whitman, there’s an opportunity to recalibrate.

In the exhibition’s accompanying guide, Curator of American Art Jeffrey Richmond-Moll says, “Given that our university stands on the ancestral homelands of these tribes, this exhibition is therefore a crucial opportunity for the Georgia Museum of Art to reevaluate its collection, the broader art historical canon, and the institution’s relationships with Indigenous communities.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.