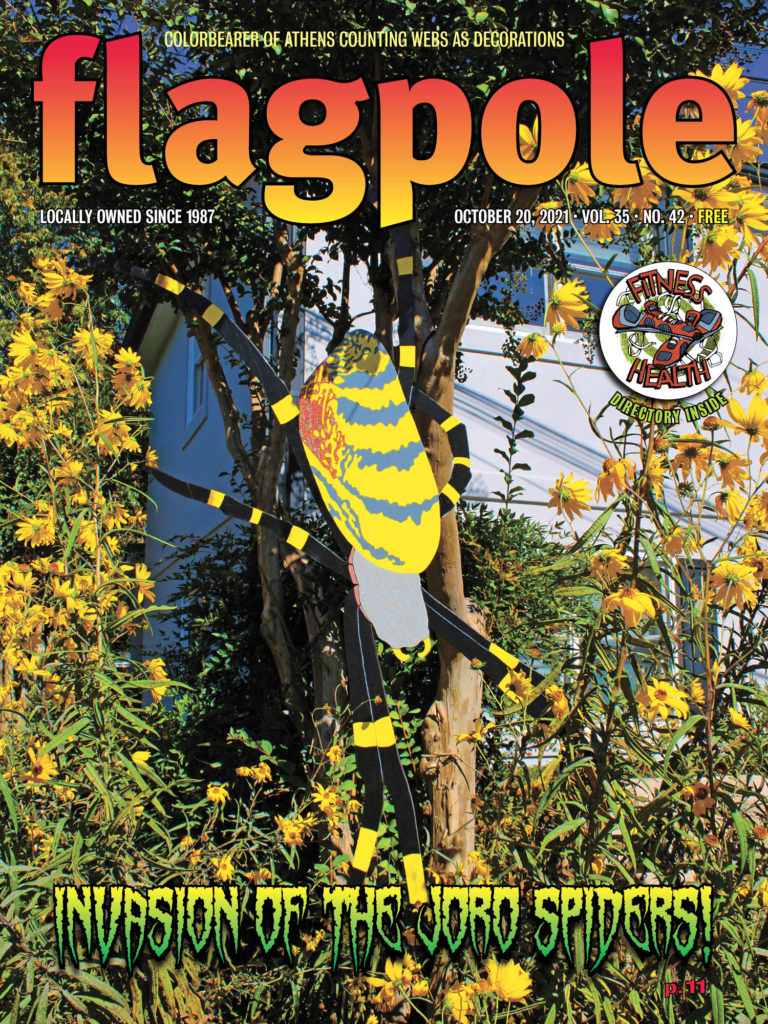

Got Joro spiders in your yard or the woods behind your house? Richard Hoebeke doesn’t want to hear about it anymore—unless maybe your yard happens to be in Alabama, North Carolina, South Georgia or somewhere else outside the North Georgia counties the Asian spider has now colonized by the millions.

Seven years ago, Hoebeke, an entomologist with the Georgia Museum of Natural History and the University of Georgia Cooperative Extension, asked an Athens newspaper reporter to publish an article about the brightly colored arachnids, common in eastern Asian countries, but never until then identified in North America. A Madison County man had found one near Colbert in 2014, knew he’d never seen one before, and brought it to the Natural History Museum for identification. Hoebeke and museum director Byron Freeman hoped people reading the article would contact them with photos if they’d seen any of the new arrivals.

Emails and photos began trickling in after the article was published—enough to establish that the spider had set up housekeeping first in the Braselton area in about 2013 and possibly earlier. Trichonephila clavata likely arrived in Georgia in a shipping container or truck traveling along I-85, Hoebeke said—another one of the dozens of foreign spider species that have hitched rides on ships and begun spreading in America, along with thousands of new insect species. Some seem to have almost no impact. Some are devastating, like the hemlock wooly adelgid that’s wiping out hemlock trees.

In the years since that first Georgia Joro sighting, Hoebeke and Freeman have been tracking the spider species’ spread. They also established that the spider’s genetic makeup most closely resembled that of Joros from Japan and China, and discovered that the new American Joros come in more than one color pattern. Most have yellow and black legs, but some have entirely black legs.

The big spider is now established in about 30 North Georgia counties, including Clarke. It has reached the western Atlanta suburbs, north nearly to Tennessee and east into South Carolina, with sightings south to about Interstate 16. Just a couple weeks ago, Hoebeke got photographic confirmation of a North Carolina Joro for the first time, in Chimney Rock.

This year, the Joro invasion appears to have entered a new phase. It’s not so much another big expansion of the Joro’s New World range—that expansion seems to have possibly slowed, Hoebeke said—but an explosion in the sheer density of the Joro population. “This year, I have answered hundreds of emails,” Hoebeke said. “They’re not seeing just a few. They’ll say they’ve got literally hundreds of them.”

Almost all this year’s reports have been from places where the Joro is already confirmed to be, Hoebeke said. Now, right at Halloween, is the peak time of year for the Joros, which will die off as the weather gets cold in November, leaving behind egg sacs with hundreds of future Joro babies inside. For now, they seem to be everywhere in Clarke and other Northeast Georgia counties—millions of them in their sprawling three-dimensional, gold-colored, bug-trapping webs, each harboring a big female and one or more of the much smaller males, who seem to move from web to web.

They’ve been a big topic of discussion on backyard gardening and hummingbird Facebook pages lately, in debates on whether they pose an ecological threat or advice on how to get rid of them. One Facebook poster said he’d rid his yard of Joros by sucking them and their webs up with a portable vacuum cleaner.

“I don’t usually kill spiders (or any bugs)…” wrote a Clarke County man, “but I’m about to get a flamethrower for these new mf’ers taking over my porch and yard.” Even flamethrowers won’t stop the spread of Joros, though. They are already too entrenched, according to Hoebeke and other UGA entomologists.

One Gainesville woman reported seeing hummingbirds entangled in a Joro web, and social media reports that Joros kill hummingbirds are now widespread. Joro females can be big enough to cover the palm of a person’s hand, but they aren’t really a threat to eat hummingbirds, said Hoebeke. He has not found any actual reports of a Joro devouring a hummingbird. Hummers may get snared by a Joro’s golden web, but are strong enough to escape, he said.

Though Joros can inflict a painful bite to a person, they’re too small to inflict serious damage. They don’t attack, but will flee from people given the chance, Hoebeke said. Bites seem to occur only when someone accidentally brushes up against one of the big females, according to the entomologist.

The jury’s still out on Joros’ ecological impact, but they don’t seem to be particularly harmful, he said. Anecdotally, some gardeners are reporting that the native garden orb weavers that once built webs in the gardens have disappeared as Joros move in, but Hoebeke and Freeman have observed native spiders co-existing with the Joros. “I see no evidence of that [displacement],” Hoebeke said. Native mud dauber wasps have found the Joro to be a good prey, and other predators may also discover them as a food source, he said.

Some entomologists hope the Joros can actually be helpful for agriculture. Their prey includes brown marmorated stink bugs, a foreign invasive insect pest other orb-weaving spiders seem to disdain. But like other spiders, the Joros eat what they can get, including the kinds of insects gardeners and farmers like to see. “There are hundreds of these beasties all over the place around our hives, and every single web is loaded with dessicated bee carcasses,” wrote a Canton honey producer on Facebook.

Good or evil, the Joros are here to stay and will keep expanding their territory. Joros can move by hitching rides on vehicles, or by “ballooning,” or launching themselves into the air by ejecting triangular silk structures that act as wind sails, perhaps powered by static electricity more than wind. “I don’t see any restrictions to this trend of expanding their range,” Hoebeke said.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.