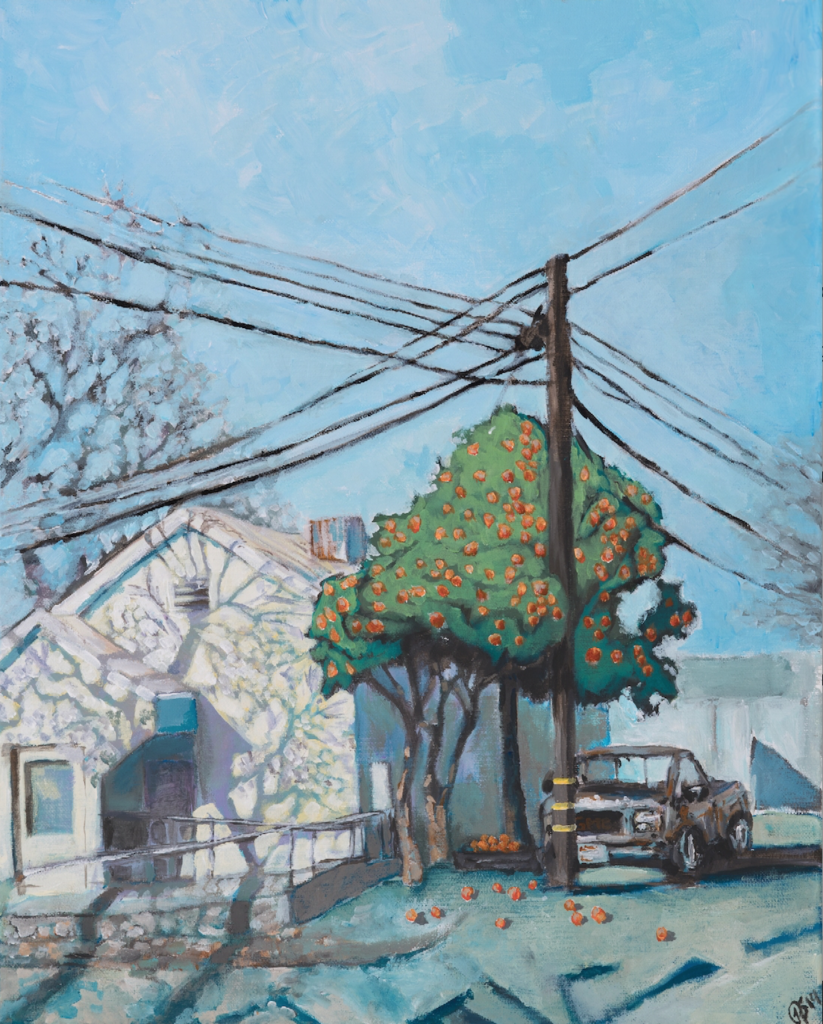

For well over a decade, Nana Grizol has crafted tender folk-punk melodies that serve as cathartic, vulnerable reflections on the Southern queer experience. After relocating to New Orleans in 2015, singer-songwriter Theo Hilton now has enough distance to view his hometown Athens from a new vantage point—a place that, despite celebrating itself as a liberal island in a sea of red, still passively harbors many of the same injustices and inequalities that plague the larger region. The band’s fourth studio album, South Somewhere Else, not only re-examines Hilton’s self-identity and personal concept of home, but confronts a complicated history of place, where rose-colored romanticism often obscures an underlying perpetuation of racial violence.

The album was recently co-released through record labels Arrowhawk and Don Giovanni. Creating the album involved several commutes back to Athens to practice with longtime members Matte Cathcart, Robbie Cucchiaro and Jared Gandy, as well as a week-long trip to Legitimate Business Studio in Greensboro, NC. Though primarily written and recorded last summer, the lyrics swiftly traverse subjects that are all the more pertinent today, as the Black Lives Matter movement spurs a long-overdue cultural overhaul. Hilton considers a significant influence of the album to be the LGBTQ liberation organization Southerners On New Ground, which has informed his personal pursuit into abolitionist political work and solidarity-building. Marginalized as a queer person, yet privileged as a white cisgender man, he uses his musical platform as a call for activism, allyship and accountability of both ourselves and our communities.

“The album’s lyrics contemplate my own socialization as a white, male-bodied queer person in a Southern college town, and try to parse out ways in which that conditioning is ever-present in my experience,” says Hilton. “My hope is that these songs can contribute to an understanding of how our lived experiences relate to structures of power—both in terms of what we can attain, and what we can imagine.”

Below, Hilton presents a track-by-track guide—partially adapted from a Q&A with Rashaun Ellis, who wrote the band’s recent bio—for listening to South Somewhere Else.

“Future Version” is a song for our younger selves. Or rather, it’s a song for the selves we see in our younger friends and family members, who remind us of the wonder and the heartache that we feel at different times in our lives—and the wonder one could never imagine until one feels it! The first song on the album is actually the last one that we wrote the lyrics to. The song was inspired by a conversation with our good friend, Jess, while we were recording in Greensboro, NC. She wrote great lyrics about the same concept.

We wrote “Jangle Manifesto” really early on in the process of the album. It’s really about the idea that powerful narratives—like those informed by nationalism and capitalism—really work to divide people from one another. It introduces a major theme on the record, which is the ways we are taught to understand the world through categories that exist to oppress.

“Plantation Country” is a protest song about tourism branding of the southeastern United States. The song asks what it means for state tourism boards to promote whitewashed versions of these places as sites of leisure, and the psychic damage these narratives do. It probes how symbols of white supremacy simultaneously uphold and obscure present-day connections to plantation pasts. Written from the perspective of someone socialized as white in the shadow of these places, “Plantation Country” explores the hurt these narratives continue to inflict. It looks to self-work and solidarities across difference for the potential to unlearn this harmful conditioning.

“Not the Night Wind,” which is about learning how to find queer connection, could be taken a lot of ways for thinking about family and intimacy outside of nuclear, heteropatriarchal constructions. I wrote it on tour, thinking about the people I’m close to that I see for a day, or a few days, and then leave, or people I’ve felt some kind of intimacy with soon after meeting and maintain a connection to as pen pals and friends.

“South Somewhere Else” is about growing up in Athens in a white, liberal, university-educated family, and feeling a sense of measured distance from “the South” and the complicated histories of place. I remember as a kid feeling like relatives elsewhere in the region were worlds away, and like we were somehow more enlightened because we lived in this college town and knew people from other college towns. These binary constructions enabled us to tell ourselves a story that “racism isn’t here, it’s there,” or “homophobia isn’t here, it’s there,” etcetera. That narrative, in turn, kept us from asking questions about the segregation and exclusion all around us.

It was really hard to begin reckoning with that. Talking about whiteness means white folks acknowledging the ways that we reap benefits from investing in white privilege every day. That’s not just in Athens, or in “the South.” That’s all of us white folks, everywhere. We need to be really skeptical of the impulse to try to locate ourselves outside of it. And most importantly, we need to stop buying into histories and political frameworks that center the actions and desires of a few white men.

“Quiet, I Can Feel It” is about trying to let go of the simplistic narratives we tell about ourselves and our relationships. My experience of queerness is made possible by so many people’s different stories and expectations and dreams and activism and lives and deaths. This song thinks specifically about the queer rights movement, about ACT UP and Stonewall, and how those stories are so important for us to understand what we’re doing today. And it’s about how one of the best parts of those movements is that they fought for queer people to be themselves in expansive ways—that’s so important to not forget.

“We Carry the Feeling” is about my experiences of what it felt like to be a queer person in the Athens punk scene of the late 1990s and early 2000s. In that community, I discovered leftist politics and aesthetics, and my queerness found some sense of acceptance, but never quite inclusion. I didn’t have the language for it then, and I was unable to see how heteronormativity rigidly shaped the expectations of people around me, as well as my own self-perception. I learned that the collectives we create are always imperfect; we perpetuate what we critique in ways that are often difficult to see.

I wrote the lyrics for “Autumn” in the car while listening to an audio book of Toni Morrison’s God Help The Child, her last novel (she read all her own audiobooks…so cool!). Like much of Morrison’s work, it also talks about reckoning with constrictive narratives. There’s this section three quarters of the way through the book where the protagonist is thinking about his childhood and this terrible thing that happened to his brother, and how that shaped his understanding of himself and the world, and it just fit in along these themes we were already working with about socialization and breaking out of structures—and so I just kept pulling over and writing lines.

“Brilliant Blue” is kind of a continuation of “Bright Cloud” from Ursa Minor. It is about exploring openness in a primary relationship, moving forward but never feeling super linear in that, and learning to stay open to what may come as you settle down in some ways.

“About the Purpose That We Serve” is kind of bratty. It’s about believing that we all have the power to see and change the world within us, and we’ve got to listen to each other and trust each other and ourselves to try to make good choices. And to put more trust in each other than people who are positioned as “experts.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.