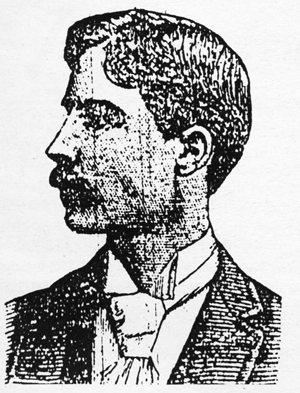

James B. Osborne

The Osborne brothers are forgotten today, but a hundred years ago they were as famous—or notorious—as any set of siblings in Georgia. One or the other was rarely out of the public eye from 1893 until 1899, when both disappeared from the state.

James B. and Benjamin H. Osborne were the first and last of the four children of James M. and Mary E. Osborne of Atlanta. Their father, the son of a Union County farm family, left the mountains around the time of the Civil War and came to Atlanta to work as a carpenter and machinist. When he was in his late thirties he married Mary Sample, a young widow with two children. He bought a house at 156 Chapel St. where the family would live for the next 30 years. Their children, born at two-year intervals starting in 1868, were James, Edward, Ann and Benjamin.

When James B. Osborne graduated from high school he went to work as an apprentice house painter and was ordained a minister in the Congregational Church. Congregationalism was brought south by New England missionaries after the Civil War. Most white Southerners saw it as a dangerous influence, and, indeed, its Southern clergy, both black and white, have a long tradition of political activism; Ambassador Andrew Young and radical poet and labor organizer Don West (like Osborne, of Union County heritage) are two 20th-century examples. After his ordination Osborne went out to California, where he worked as a house painter and became an active union member and organizer.

In May 1892 James Osborne represented his local at the statewide labor convention in San Francisco. The convention chose him as a delegate to the California People’s Party convention. Populism was largely a farmers’ movement, but many of its tenets, including public ownership of transportation and utilities, and free coinage of silver to increase the money supply, appealed to the urban working class.

Osborne joined the Populist Party and was appointed state lecturer for California, traveling throughout the state as a speaker and organizer. Within a year he had moved to Colorado, where he continued to work in behalf of the Populists and his union, the Brotherhood of Painters and Decorators. In July 1893 the Colorado labor convention chose him as a delegate to the Chicago silver convention, a national meeting to support currency reform.

After the convention was over Osborne returned home to Atlanta. Atlanta’s factories were laying off thousands of workers and the rapidly growing Populist Party was looking for allies among the unemployed for their battle against the conservative Democrats. On the night of Aug. 12, Osborne addressed over 2,000 people at the public artesian well on “The Relation of Silver to Labor.” Three days later he gave what the Journal described as “a strong talk” at Atlanta’s Industrial Council Hall.

Two days later he addressed a mass meeting of businessmen and laborers at the Fulton County courthouse. The meeting was meant to be a pleasant one stressing the essential unity of interest between capital and labor and calling for everyone to fight the economic crisis by buying more locally-made goods. The proceedings followed the chummy script until James Osborne took the floor. He addressed his audience as “Fellow citizens, fellow laborers, fellow slaves.” “Talk that way!” and “Talk bread!” came cries from the floor. “Bread! Bread!” bellowed Osborne, “The reason I haven’t got much bread is because some sucker would work for 50 cents less a day than I would and because I am willing to pay 50 cents more for protecting labor than some of you scabs.”

Two nights later Osborne was again at the artesian well addressing a crowd of unemployed workers. He spoke frequently at the well, Atlanta’s traditional arena for public speaking, and his speeches, often announced in Tom Watson’s People’s Party Paper, drew larger and larger crowds.

Atlanta’s police force grew alarmed at the size and frequency of these gatherings. They banned David Marion, aka “Doctor Swamp Angel,” an eccentric patent medicine salesman and Populist speaker, from the well. Police Chief Connolly sent Osborne a letter saying “you will not be permitted to address a meeting at the artesian well on Wednesday or any other night. If you intend having a meeting you must hold the same in some hall, as the streets of the city is not the place to have these meetings.” Osborne announced that he would not be scared off from addressing a peaceable public gathering and put out word that 7 p.m. Sept. 13 he would speak at the artesian well on “Christian Aspects of the Labor Problem.”

© 1994 John Ryan Seawright

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.