Orth Harper Stein turned 30 in January 1893. In the 12 years since he had left his home in Indiana he had become famous as a reporter, artist and poet; gotten drunk with Oscar Wilde in Colorado; killed a man in Kansas City; bankrupted his widowed mother; scandalized St. Louis by living with a prostitute; left a trail of forged checks across the continent, and slaved as a convict laborer in the Florida phosphate mines. He came to Atlanta in 1891 and was wrongfully arrested as a fugitive, but was treated with such kindness that he stayed in the city as a writer and artist for the Journal. In late 1892 Stein began his own weekly newspaper, The Looking Glass, which was to amuse and scandalize Georgians for the next six years.

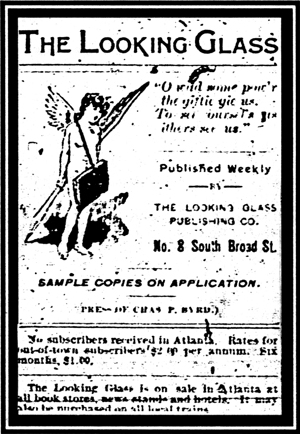

The Looking Glass was a 12-page paper published every Saturday morning. Its masthead gave the following information:

No subscribers received in Atlanta. Rates for out-of-town subscribers $2.00 per annum. Six months $1.00. The Looking Glass is on sale in Atlanta at all book stores, news stands and hotels. It may also be purchased on all local trains. Gossip sketches and pictures solicited and if accepted, liberally paid for. The Looking Glass has by far the largest street sale in Atlanta.

The Looking Glass was cleverly written, beautifully designed and printed, and lavishly illustrated, but its great success depended most on its editorial policy: Orth Stein would print news and gossip that no other editor in the state would touch with a 10-page lawsuit.

A glance through the first few pages of the April 7, 1894, issue gives some idea of The Looking Glass’ appeal. The front page is dominated by a cartoon of a man standing atop a wrecked building like a pot-bellied colussus, gazing down at a pile of wreckage bearing the sign “Lumber for Sale” in the street below. The colossus is “Uncle” Jonathan Norcross, a founding father of Atlanta, one of the city’s wealthiest, most powerful and, at age 99, oldest citizens. Uncle Jonathan owned the property at the corner of Marietta and Peachtree streets in downtown Atlanta and had let his buildings run down to the point where they were not simply uninhabitable, but were basically collapsing into one of the city’s busiest intersections. No politician in the city dared tell Uncle Jonathan to clean up his mess; the Journal and the Constitution made discreet hints and complaints about the situation from time to time. It remained to Orth Stein to shell down the corn in the following manner:

Hon. Jonathan Norcross is an old and well known citizen of Atlanta. By strict attention to the almighty dollar he has succeeded in amassing large wealth, the mesmeric effects of which are exceeding obvious in the extraordinary privileges he enjoys. If a poor and humble citizen disregarded public rights and outraged his neighbors as he has done in this instance, the aforesaid poor and humble citizen would have long ago landed in the bastille.

The second page contains a long article on slot machines in Atlanta and the legal crusade against them, and also a picture of a young Cobb County woman posing beside her bicycle wearing short pants and stocking which show her naked knees, strong stuff for the reading public in great-grandma’s day. Page three has an account of an unnamed prominent Atlantan chased out in the street by his wife without his trousers. Across the page is a poem, probably by Stein, titled “The Devil to Dine,” which runs, in part:

I’ve invited the devil to dine tonight;

He’s a most agreeable fellow,

And I’ve ordered a dinner that’s out of sight;

It would tempt the soul of an anchorite

Or make a cardinal mellow.The only thing that I’m puzzled about

Is who to invite to meet him.

There are plenty of folks who would come, no doubt,

And run the risk of a case of gout

For merely a chance to greet him…I think I shall ask a Peachtree dame

Who flouts the world with an antique lover.

He has little to boast but a proud old name,

And he’s smirched that well with their shameless shame,

He shall have the opposite cover…Next to him comes a gay M.D.

Who burns both ends of the candle.

Ha! ha! the hubbies who pay his fee

They say he has ruined two or three

And kicked up a deuce of a scandal…

At the foot of the page is reprinted a paragraph of glowing praise for The Looking Glass from the pages of the Constitution. The fourth page contains opinionated paragraphs of national, state and local news, including several blasts at South Carolina’s new liquor laws, a plea for the Atlanta City Solicitor to be paid a salary instead of fees, and a call for the abolition of “that dismally stupid institution known as the coroner’s jury.”

At this time The Looking Glass was about 18 months old and selling plenty of advertising, about a quarter of the paper’s linage. Orth Stein seems to have been doing well, but he had only begun to dabble in scandal, and advertising revenue was not the only payment he was to receive.

© 1994 John Ryan Seawright

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.