You may have seen him walking down Lumpkin Street toward Park Hall, or walking back in the opposite direction, headed home for lunch. In his later years, his pace slowed, but colleagues in the Classics Department could still set their clocks by him, could depend on his daily routines as a reflection of their own. “In a way,” says Erika Hermanowitz, a longtime colleague, “we revolved around him.”

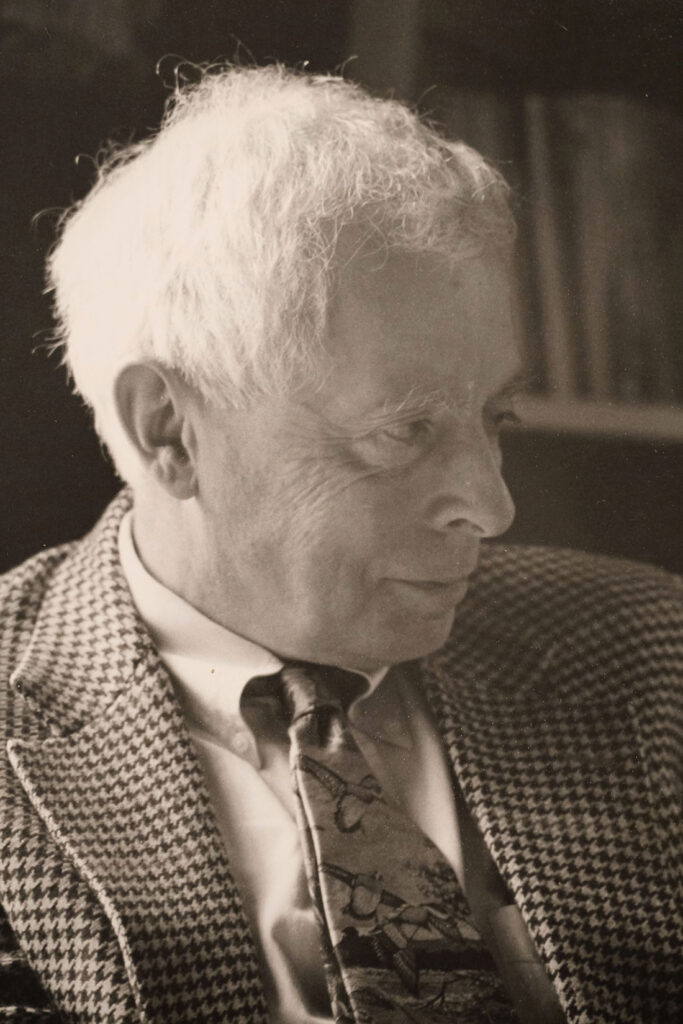

Robert Harris, known to his friends and family as Pete and to his colleagues as Bob, was 89 years old at the time of his death on Dec. 13, 2022. He came to the University of Georgia in the fall of 1963 and taught in the Department of Classics for 57 years. In colleges and universities, some exposure to classical education has long been considered necessary to the creation of a literate citizenry, and Robert’s life as a teacher through the changes of over half a century never lost that sense of necessity, that urgent connectivity to the past that enlivened his teaching of medical terminology, classical culture, classical mythology and Latin for each new generation of students. As Robert’s brother Richard Harris says, “When I first learned of my brother’s passing, I couldn’t help but think of the ‘Superman’ lyric from the Crash Test Dummies: ‘And sometimes I despair the world will never see another man like him.’” Certainly, UGA and Athens have lost a unique presence.

His students loved him. Thiela Falkenstrom Schnaufer, who taught Latin for 33 years after graduating from UGA, says, “He was the best teacher I ever had. He had a permanent twinkle in his eye which seemed to come from the delight he took in what he did. He loved to play the part of eccentric classicist while beguiling students who pursued every major and vocation with his ability to make word derivatives fascinating, ancient history brand new, and dead languages come alive.” According to Hermanowitz, “They would start out with his medical terminology course and then take every single class they could with him. He brought in his stamp collections, flowers from his garden, the clavichord he had built himself. They found him charming.”

Robert grew up in a small town near Niagara Falls, NY, where his father worked as a research chemist. Wanting the four boys to have fresh air and access to the outdoors, the parents purchased an old stone farmhouse about 25 minutes away from Niagara. Not until they moved in did they realize that the local grade school—two rooms and eight grades—was three miles away. For a time, the boys’ mother taught them at home, but after a visit from a school district representative, the family bought a second car and the boys started school: Homeschooling was not legal in New York in those days.

Robert’s childhood included idyllic summers in a family cabin in Ontario with no electricity or running water. During one summer, he built a clavichord “from scratch,” using only hand tools. He did purchase a keyboard, but the rest of the instrument was his own construction. Michael Harris, Robert’s youngest sibling, remembers Robert playing the preludes and fugues of Bach on summer evenings by the light of a Coleman lantern. Michael, perhaps because of the 14 years separating him from his oldest brother, saw Robert as a mentor and teacher; in addition, Robert must have delighted his youngest brother by building a red car for him, sort of a soap box derby vehicle—except that it was a Model A—with a knee action suspension and tiller steering created from an old swing.

Robert’s brother Richard, seven years younger, also remembers Robert’s role as a mentor in his own life. He says, “As I entered adolescence, Pete corrected, advised, and encouraged me in the journey towards adulthood. He helped me with my writing. And did what he could for my thinking.”

Robert had a mischievous sense of humor. He once said that the secret to good teaching was “to belabor the obvious.” According to Schnaufer, “There were rumors that he never made a left-hand turn in his car, and that the clavichord in his office was really a child’s coffin. He did nothing to dispel these rumors, and may have even been their source.” Lee Shearer, longtime Athens journalist, recalls a class in which Dr. Harris was describing the Acropolis of Athens and how it symbolized the Greek ideals of democracy and civilization. “Then he said, ‘we have a similar landmark here in our Athens, also symbolizing our ideals: the C&S bank building downtown,’ which at that time had a lighted sign visible from miles away.”

For a time after he came to UGA, Robert walked everywhere, as he had never learned to drive. Eventually, though, he decided he might need a car to facilitate his antique shopping, so he went out to Trussell Ford and bought a 1965 Ford Falcon at the asking price. He didn’t think to haggle, but he did have one requirement: He would only buy the car if the salesman would teach him how to drive. Thomas Harris, the closest brother to Robert in age, remembers, “The story had a happy ending: Pete learned to drive, got his license, and drove that car until it was a pile of rust.” (Thomas confirms the rumor about those left turns: “He would make three rights to avoid turning left.”)

In his early years at UGA, Robert walked to work wearing one of his two shiny black suits, “heavily impregnated with chalk dust,” according to his wife, Ellen. During the late ‘60s he adopted the more casual styles then in vogue, but at some point—nobody is quite sure exactly when—Robert began to dress more distinctively: brightly colored trousers, windowpane plaid jackets, brilliant bow ties and his favorite brick-red shoes. In summer, he might sport a straw boater; in winter, a brown felt hat or perhaps a stocking cap with ear flaps and tassels. His brother Richard suggests that Robert saw in himself the image of the Southern 19th century professor; his manner of dress was—with his lovely garden, his collection of antiques, his accomplishments on the piano—all part of a “commendable task of self-realization.” Hermanowitz echoes this view: “He was a throwback to another century. His office had no desk, no fluorescent light, only a big overstuffed chair, beautiful 19th century books, stationery, antique rugs–it was like a gentleman’s study from the past.” Richard adds, “The world of the qualitative life—historically, a Southern ideal—was much diminished with his passing.”

In retrospect, the qualitative life that Robert created for himself seems to have been in place from his earliest days. As a small child, he would ask his father to read to him every evening from a couple of coffee-table art books, studying the pictures as he listened. At a major art exhibition in Buffalo, NY, Robert was able to identify many of the artists on display—Rembrandt, Picasso, Gainesborough—and kept up a running commentary as the family moved through the exhibit. “Soon,” says Thomas, “we had a cluster of people following after us to hear his commentary.”

As a child, Robert gardened, studied the piano, started a stamp collection. All of these pursuits, with the addition of collecting antiques, were touchstones for his entire life. His love of music dovetailed with his antique collecting, and he eventually had six pianos in his home, as well as various clavichords and harpsichords that he built himself. Until almost the end of his life, he played the piano every day.

And he gardened. From the 400 boxwoods that he planted himself when he and Ellen moved into their home in 1994 to the exuberant yearly display of tulips flanking a wide front sidewalk, his garden was both a showplace and a sanctuary. Mary Kelly, a neighbor and avid gardener herself, describes Robert’s singular ability to encourage and support a fellow gardener: “Robert would drop by my house and notice something I’d done, something like pulling a rose into a particular direction, and he’d say, ‘Now, Mary, how ever did you think to do that?’ I knew that his expertise went far beyond the little thing I’d done, but he still just had that way of making me feel good about my idea.”

Teachers, it’s said, never know where their influence ends. Robert was present in the lives of his students at the moment when, for so many of them, a college classroom could be a portal to the future they were just beginning to imagine for themselves. Robert’s ability to animate the past and his generosity in offering up the example of his own qualitative life for observation and study offered a throughline of more than half a century. As Erika Hermanowitz observed, “He taught an elegant and simple aesthetic. He taught beauty. He showed his students a gentle side of the world.”

A Memorial Mass and reception will be held on Saturday, Mar. 25, 2023, at 11:00 a.m. at The Catholic Center at the University of Georgia, 1344 S. Lumpkin St., Athens, GA 30605.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.