Former UGA Dean of Men and Dean of Students William Tate once proposed to write a three-part series for The Athens Observer recalling Athens as he knew it during his years as a student here, 1920-24. The dean’s method would be to walk down Prince to Milledge, thence to Five Points and back to town on Lumpkin, recalling only from memory buildings and the people who lived and worked in them during his years of matriculation. As the dean waded through his flood of recollections, the series grew into 17 fascinating Observer installments, later collected into his book, Strolls Around Athens—still a rich read if you can get your hands on a copy.

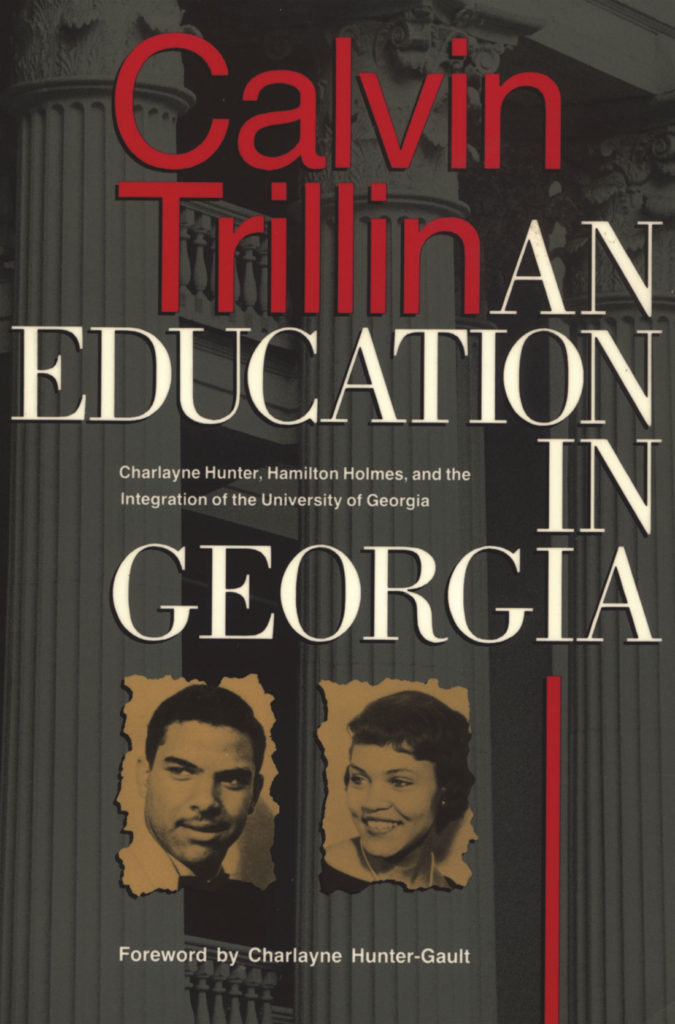

I will follow Dean Tate’s method here, relying only on my memory. Fortunately, my recall is much inferior to his, even though I have already cheated by re-reading Calvin Trillin’s An Education in Georgia.

These ruminations are occasioned by the 60th anniversary of racial integration at the University of Georgia in 1961, currently the subject of a series of events on campus. I was a junior during the winter of 1961, so I had a ringside seat.

In federal court, right here in Athens, we sat spellbound as the chancellor of the University System of Georgia, the UGA president, the registrar and other top officials took the stand and—under oath—denied that UGA had any policies excluding Black students. Dismissing those transparent prevarications, the court ordered the immediate admission of Charlayne Hunter (now Hunter-Gault) and Hamilton Holmes, two Black students from Atlanta.

This action came during the civil rights movement, when other Southern colleges had been integrated amidst rioting and bloodshed, so a corps of veteran reporters descended on Athens, ready for the next wave of mobs and tear gas. And we did have our mobs—groups of students gathering to chant “[N-word] go home” and to impress their English profs with such rhyme schemes as “Two, four, six, eight/ We don’t want to integrate.” Groups of students gathered in various places in crowds at night, working up to the full-fledged riot that came later.

But we did have Dean Tate. He had not been among the administrators lying in court, and he simply went about fulfilling his duty to protect the safety of all UGA students, now including, for the first time—except for a bunch of foreign students—two of color.

Dean Tate by that time was already a campus legend, a stern disciplinarian who, as a former UGA track star, could easily outrun underclassmen fleeing the scene of infractions. At that time, the university had the legal status “in loco parentis,” meaning that while you were enrolled and in town, UGA was your parent, and Dean Tate was your enforcer-uncle. Your ID card was your passport. Without it, you were no longer a student. If the dean got your card, he owned you. When push came to shove, Dean Tate could grab you with one hand and your wallet with the other, and immediately the future of your college education depended on what transpired when you showed up at his office on the day and time commanded.

Dean Tate could read a crowd. He knew when to be firm and when to be jolly. He waded into a crowd of angry undergraduates in front of the Arch on one of those nights and just started talking to the boys. He approached one and said, “Boy, what’s your name?” The kid stammered out his name, and the dean asked where he was from and then if he might be the son of so-and-so up there, which, it turned out, he was, so Dean Tate launched into a long anecdote about the misdeeds of the father while he was an undergraduate, and, before long, the whole group of boys was laughing and drifting away, dragging their Confederate flags behind them.

But wait: I see that by invoking the dean, loquaciousness has crept into my account to the extent that it must be concluded next week. Meanwhile, I urge you to obtain a copy of Trillin’s An Education in Georgia. This is important because UGA Press is sponsoring a campus read of the book (reprinted by the Press in 1992), and, on Thursday, Feb. 4 at 4 p.m., Trillin and Hunter-Gault will have a virtual conversation about the integration of UGA (ugapress.org/kick-off-event-an-education-in-georgia-then-and-now/).

Next week, I promise rioting, tear gas, flying rocks, the KKK and one pissed-off reporter. Meanwhile, you can familiarize yourself through photographic and memorabilia exhibitions at the main UGA library and the Special Collections Libraries on campus.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.