Several downtown and Midtown Atlanta water mains broke simultaneously in May, forcing businesses to close and residents to boil water for nearly a week, and Megan Thee Stallion to cancel a concert, until city workers made repairs. But Athens-Clarke County officials say they’re confident a catastrophe of that magnitude is unlikely to happen here.

“[ACC Public Utilities Department (PUD) staff] goes above and beyond making sure quality water is coming out, fire protection is happening, all that,” PUD Director Hollis Terry says.

Atlanta officials attributed the main breaks to aging infrastructure—some pipes in the city center are 100 years old. In Athens, all of the old cast-iron pipes downtown that dated back as far as 1893 were replaced as part of various streetscape projects, such as the recent Clayton Street infrastructure overhaul, according to ACC Public Utilities Department officials.

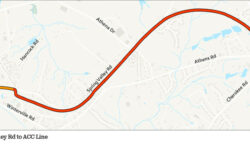

ACC is also in the process of replacing aging pipes elsewhere in the county, and adding new ones. Every five years, PUD updates its 20-year service delivery plan. As of 2020, the most recent update, Athens had a little more than 800 miles of water lines. About 100 miles have been added in the past four years. The 2020 service delivery plan calls for spending $400 million on water and sewer infrastructure, including $20 million to upgrade aging water mains.

“It’s all over [the county], and a lot of times that has to do with age,” Terry says.

“We may replace a line if it breaks every three months,” Assistant Director Hugh Ogle adds. “It depends on the service history.”

But overall, even the old cast-iron pipes “were in very good shape for what they are,” Ogle says. Those older pipes tend to become brittle over time. The city now uses pipes made out of ductile iron for water mains.

In addition to replacing aging pipes, many of which are now too narrow in addition to becoming brittle, PUD is also continually expanding the water system so that there are multiple routes for water to flow to customers. That way, the water stays on even if a main breaks. “We have so much redundancy, [a complete shutoff] is unlikely to happen,” Terry says.

Boil-water advisories are rare in Athens. When a main does break, though, sometimes water customers will see discolored water coming through the taps. Minerals in the water accumulate in pipes over time, and when pressure drops they get stirred up, Ogle explains. But the minerals are not harmful, he says.

With 200 employees and an operating and capital budget of nearly $60 million for 2025, PUD is one of the largest departments in the ACC government. The department is funded primarily by ratepayers and does not receive property tax revenue, but it does receive sales tax funding for some capital projects. Those costs, however, pale in comparison to what Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens has said will be billions of dollars worth of repairs to the water system in Atlanta.

Dickens is not the first mayor to ask for federal assistance in tackling long-overdue water infrastructure projects. The Jackson, MS water system nearly collapsed in 2022 after decades of neglect and disinvestment due to white flight and a shrinking tax base. A torrential downpour made water from the Ross Barnett Reservoir harder to treat, and the resulting slowdown at the city’s two aging treatment plants caused dangerously low water pressure for many of the city’s 150,000 residents.

The crisis in Flint, MI was even worse. In a city with a decimated tax base much like Jackson, an emergency manager appointed by the governor stopped buying Lake Huron water from nearby Detroit and started drawing it from the polluted Flint River to save money. The water caused an outbreak of Legionnaires disease and it corroded lead pipes, exposing thousands of children to dangerously high levels of lead.

“To make a comparison between us and Flint would be impossible,” Ogle says. For one thing, Athens’ sources of raw water—the North Oconee River, Middle Oconee River, Bear Creek Reservoir in Jackson County and, within the next decade, an East Athens rock quarry the county bought in 2020—are much cleaner to start with. For another, PUD conducted a survey looking for lead water mains and has not found any, although it’s possible some buildings have lead pipes on private property, because PUD’s responsibilities stop at the edge of the right-of-way.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires utilities to test water frequently and issue a report on water quality each year. The most recent report in 2023 found that Athens’ drinking water met all federal standards.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.