Athens-Clarke County commissioners have mixed opinions on how to fund Athens Transit, making it unclear if the current fare-free policy will be able to continue. Despite the benefits that fare-free bus service provides the community, two commissioners said they wanted to bring back fares.

“We need to charge fares,” Commissioner Dexter Fisher said during a discussion at a January retreat. “No operation can be sustained if it doesn’t have income.”

Commissioner Ovita Thornton agreed, saying that the bus route near her house rarely has any passengers. “I don’t know if it’s the best use of money,” she said.

While most transit systems generally charge passengers a fare to support transit operations, not all transit systems are funded that way. UGA Campus Transit, for example, is funded primarily through a fee charged to all students, whether they ride the bus or not. Athens Transit operations are mostly funded through sales taxes. This year, the 1% sales tax for transportation projects is estimated to provide the bus system with the most revenue it has ever had, fares or no fares.

In some cases, going fare-free actually relieves the burden on taxpayers and frees up money that could be used for transit expansion or other purposes. For example, Boone, NC has had a fare-free bus system since 2005. At that time, its fareboxes were costing the city more to maintain than the fares brought in.

Athens Transit’s fareboxes are worn out and would need to be replaced before the agency could start charging fares again. Interim Athens Transit Director Victor Pope estimates that it would cost $1.6 million to outfit the bus fleet with new fareboxes. Since these machines last about 10 years on average, purchasing them would cost Athens about $160,000 a year.

Worse, fareboxes are fragile machines that break often. Paying for replacement parts, repair and licensing for the boxes would cost another $100,000 a year. Then there are ticket-printing expenses and the cost of paying an employee to count the cash.

In fiscal year 2019, Athens Transit raised $650,000 directly through the farebox. UGA provided the system with another $528,000. Even adding those two sources together, that’s only $1.2 million in revenue. This means that if Athens Transit brought back fares, assuming it collected a similar amount, almost 25% of the revenue would be spent on overhead costs.

The source of the money used to fund transit also matters for social and functional reasons. Transit riders nationwide are more likely to have low incomes and are more likely to be people of color than those who drive cars as their primary means of transportation. This is also true in Athens, a city that’s had problems with poverty for some time.

Back when Athens Transit charged people to board the bus, fares would add up to a large percentage of some riders’ incomes every year. One round trip every day for a year at $1.75 each way would cost $1,277.50, or about 10% of the income of someone living at the federal poverty line.

Bus riders at Athens’ multimodal station told Flagpole that fare-free transit helps them afford to move around the city for work, school and everyday errands like going to the grocery store.

“I ride the bus just about every day. It’s been a big help,” said Jill Fitz. “Sometimes I do Uber or Lyft when the bus isn’t running, and it costs a lot.”

Anthony Whitlock agreed. “I take three buses a day. That [would be] a lot of money,” he said. “There’s a lot of people on the street who need food and who need to get to places, laundry or anything like that. Some people want to get jobs. It’s hard for them to travel around when they don’t have the money.”

Not only is raising transit revenue from TSPLOST more efficient in a financial sense than charging fares, it’s more efficient in a broader sense as well. Fares have a major downside TSPLOST does not—they discourage ridership.

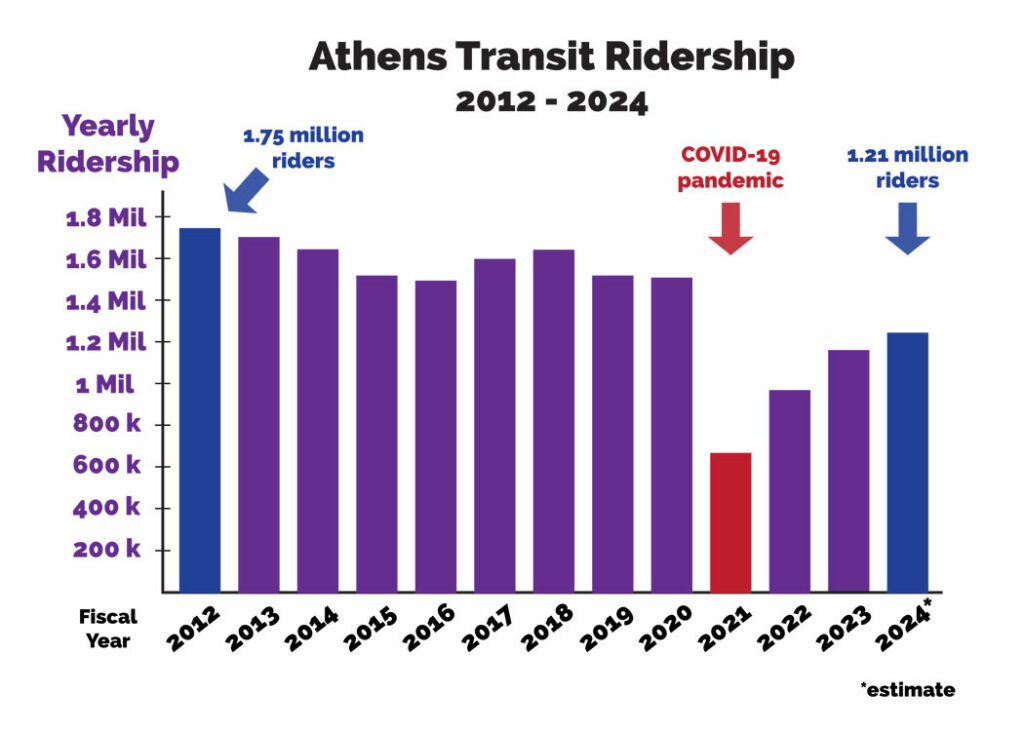

Nearly every transit system that has ever experimented with removing fares has seen a significant increase in ridership, usually between 20–60%. Athens in recent years has been one of the few exceptions to this rule. When Athens Transit removed fares in fiscal year 2021, ridership actually plummeted by 58%.

Of course, the main factor affecting ridership in fiscal year 2021 (which began in July 2020) was the COVID-19 pandemic. The University of Georgia shut down, as did nearly everything else, and people became afraid to enter enclosed spaces in the presence of other people.

Even so, the pandemic was the reason Athens Transit removed fares in the first place. The idea was to have passengers board from the rear door, bypassing the fareboxes and allowing bus drivers to maintain 6 feet of social distancing. Another silver lining of the pandemic was a massive infusion of federal dollars through the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan.

As the pandemic began to ease, inflation skyrocketed and unemployment dropped to historically low levels. That caused organizations of all kinds to have difficulty hiring. Despite the huge infusion of federal funds, Athens Transit was forced to cut routes and hours of operation simply due to a lack of bus drivers. These service hours have yet to be restored.

Pope told Flagpole that they were forced to cut almost 4,000 bus hours of operation per month due to the lack of drivers. This has prevented ridership from returning to pre-pandemic levels, even though the routes still in operation are seeing more passengers per hour after removing fares, according to Pope.

“We would see much greater ridership numbers than before the pandemic if we had the workforce,” Pope said. “Maybe back to 1.6, 1.7 million riders a year or more.”

Richmond, VA, which has a fare-free transit system, is one of just 23 communities nationwide where ridership has fully recovered from the pandemic. It solved its driver shortage by raising pay 43%, to nearly $25 an hour, and training applicants with clean driving records instead of requiring that they have a commercial driver’s license.

Pope said he doesn’t think going fare-free has contributed to difficulty recruiting and retaining bus drivers. In fact, staying fare-free might be making this problem easier to manage, not harder.

“There’s a perception that [fare-free and driver dissatisfaction] are related, but I don’t necessarily know that. I drove the bus myself for three years. During that time, my No. 1 issue would have been people arguing about the bus fare. When I had issues on the bus, it was usually someone upset for having to pay a fare. I don’t know [drivers] would find they had fewer confrontations [if we brought back fares]. It might even add a point of conflict.”

For all its benefits, fare-free transit does have some downsides. On large transit systems with a lot of riders, fareboxes can provide needed revenue that would be difficult to make up in any other way. Another downside is that fare-free transit can sometimes be a victim of its own success. If too many riders suddenly hop on board a system that’s not ready to accommodate them, buses can start being late and the whole system can suffer. Neither of these is the case in Athens.

One issue Athens does have is “problem” riders. These are people who cause disruptions, noise, foul smells or violence. These could include college students, people experiencing homelessness or people with mental health issues. Some larger cities are working to reduce the perception that transit is dangerous. For example, Minneapolis and Seattle recently started using unarmed “ambassadors” to check fares and direct riders who cause trouble to social services. New York Gov. Kathy Hoschul took a more militaristic approach, deploying 750 National Guard soldiers to patrol the New York City subway.

Problem riders can sometimes bother other passengers so much that core ridership suffers. They can also cause major outbursts or disruptions that could ruin a bus driver’s day. If that happens often enough, these badly needed drivers might quit to pursue other careers. This is a problem that seems to have gotten worse since the pandemic, but Pope said the lack of fares isn’t to blame.

“Transit is sort of like a microcosm of the community,” Pope said. “We have seen an uptick in drug-related issues and in unhoused riders. But people are using it for transportation, for legitimate purposes in a lot of cases. I don’t necessarily know that fares would influence that. I think you would still see about the same number of behavioral issues, but you’d see decreased ridership.”

On the other hand, some research suggests that transit agencies would be better off collecting fares and using the revenue to improve service. Before rolling off the commission at the end of 2022, former commissioner Russell Edwards suggested that reinstating fares could pay for shorter headways or more routes that would encourage more people to ride the bus. Of course, expanding service is impossible as long as the driver shortage persists.

Transit staff are planning to keep fares at zero for at least the next year, but the ACC Commission will make the final decision.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.