As self-affirming titles representing marginalized students are getting swept up in the undertow of book bans throughout the South, advocates say educators who choose the wrong titles for story time are now facing harsher consequences. School and public libraries around the country are experiencing a rise in challenges to books that parents complain are too sexually explicit and racially divisive for their children to consume without their consent.

Books such as Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer are among the titles showcasing LGBTQ characters and the experiences of Black and brown people that are being called into question. But the sweep of censorship has some concerned that banning these books will in turn criminalize educators, said Amanda Adams Lee, a member of the Georgia Library Media Association.

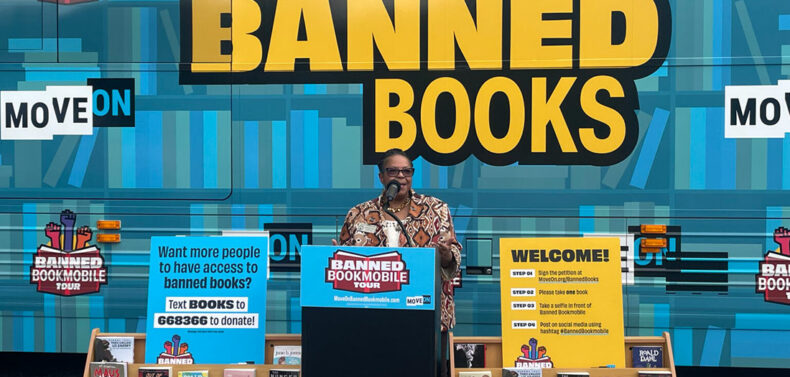

Lee, along with state lawmakers and other activists, spoke at the MoveOn Banned Bookmobile rally last month in Marietta, a Georgia stop on their tour across the country until they reached the Florida governor’s mansion. The goal is to promote inclusive learning in schools, and to advocate for educators’ right to engage with the topics of diversity, equity and inclusion in their classrooms.

The consequences for teachers are being seen in real time, Lee said, referring to Cobb County teacher Katie Rinderle, who is fighting to keep her job after she was fired for reading the children’s book My Shadow is Purple to her fifth-grade gifted class. Groups like Moms for Liberty, which the Southern Poverty Law Center calls “a far-right organization that engages in anti-student inclusion activities,” have expanded book-banning efforts across the country. A collection of legislation responding to the conservative pushback to LGBTQ+ and racial inclusivity passed in states such as Florida, Illinois and Georgia.

Last year, Georgia lawmakers passed Senate Bill 226, which prohibits the sale and distribution of harmful materials to minors. It has since led to a state board striking common words like diversity and intersectionality from teacher training materials, as well as Rinderle’s firing.

Aireane Montgomery, president of Georgia Educators for Equity and Justice, said that parents who are interfering with the educational infrastructure tend to be far removed from the academic experience. Allowing such groups to have this much influence can be detrimental to marginalized students who already don’t find themselves in the lessons being taught. “It’s very unfortunate that we’re allowing teachers, who are the professionals, to have their autonomy taken when they have invested so much of their time and money into their profession,” Montgomery said.

Sen. Chuck Payne, a Dalton Republican who was a sponsor of SB 226, said students should be shielded from sensitive subjects until they’re older, and that “we shouldn’t be trying to rush them into the world of politics.”

Even though one teacher has already been terminated in the aftermath of this legislation, Payne said school faculty should not have anything to fear as long as they are not teaching so-called divisive subjects—a standard not clearly spelled out in the law.

“There’s not gonna be a police agent out there monitoring classrooms to make sure that teachers are not saying the wrong words,” Payne said. “But at the same time, to give us a basis for [when] a teacher does go down that path, they start trying to bring an agenda into the classroom to teach kids, then it gets back to the parents, at least it gives those parents recourse.”

Others disagree. “I see this as an attack on teachers,” said Rep. Terry Cummings, a Mableton Democrat. “You know, so many things have been taken away from teachers. And now you can’t even pick up a book without being fired or terminated from your job. And so I’m here to say we’re not going to put up with it.”

Last year, Georgia ranked No. 12 among the states for banning the most titles, contributing to the 1,269 orders nationally to censor library books and resources, a record-breaking trend of censorship for libraries around the country, the American Library Association reports. Of those challenges, 58% targeted materials in schools, while 41% targeted public libraries. Nine in ten challenged books were part of an attempt to censor multiple titles at once.

“When students who are part of groups that are experiencing challenges—whether it’s because they have physical challenges, mental health challenges or are part of a marginalized group in the school community—finding books that address their concerns and answer their questions really contributes to improved educational outcomes,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom.

New Disabled South is a coalition of activists and organizations based in Atlanta focused on quality of life for people with disabilities. Though most of its advocacy focuses on equity and accessibility of care, intersectional representation is a key component to the fight for disability justice, said Dom Kelly, president and CEO of New Disabled South.

“We know that trans youth are three to six times more likely to be autistic and neurodivergent. That’s just a reality,” said Kelly. “And what they’re doing here in Georgia and across the South is they’re weaponizing autistic identity and disability to justify banning gender affirming care for trans kids.

“Their parents may not be affirming. So they’re not getting that education, and they’re not seeing themselves in these books. And that does so much harm to someone’s identity,” Kelly said.

Two counties, Forsyth and Cherokee, drove most of the book bans in the state last year, according to Pen America, which advocates for free speech on school campuses. A U.S. Department of Education investigation found that the book bans in Forsyth County may have created a hostile environment for some students.

Banning books has been an issue in America since the years soon after the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock. Critics argue this modern crusade against intersectional teachings has been fueled by a small but boisterous few that do not represent the majority of Georgia parents.

“This is why Georgia is struggling to retain teachers. This is why our public education system is failing,” Lee said. “We want our educators to be treated with respect and our children to learn diverse perspectives. It’s time for all of us to stand up and fight back.”

This article originally appeared at georgiarecorder.com.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.