It’s been a rough year in the district attorney’s office. There’s an active lawsuit against DA Deborah Gonzalez, and the state legislature passed a law targeting her and other progressive prosecutors around the state. Gonzalez has been subject to a very high level of scrutiny, which may be unprecedented for the Western Circuit, and recently sat down to discuss it.

Flagpole: When you were running for office, did you anticipate that things would be this difficult?

Deborah Gonzalez: Keep in mind that there was backlash against me even before I won the election. After I won, I thought things would calm down a little, and we could get to work. That never really happened. It started immediately with Oconee wanting to secede from the circuit. So, it’s always been challenging, but it has been surprising to me how much hostility there’s been. I’ve had my car keyed. I’ve had my backyard broken into and a noose put there. I’ve had people threaten me. It’s one thing if you don’t like my policies, but when it gets this hostile it really distracts from what we need to do.

FP: There’s a lot going on here, but first let’s talk about the lawsuit brought against you by Jarrod Miller, who owns a bar downtown. It’s a writ of mandamus, meaning he’s asking the court to order you to do your job, essentially. What’s all this about? Are there parts of the job that you’re unable or unwilling to do?

DG: You can’t say I’m not doing my job. You can only say you don’t like the way I’m doing it. This job comes with discretion that has never been questioned before, but for the first time you have a woman of color in this office. About the legislation that was passed…

FP: You’re talking about SB 92, which sets up a council to oversee prosecuting attorneys. This council would discipline attorneys if they’re found to be performing below standards, potentially including removing them from office.

DG: They tried to put that in from Day One when I was elected. It was introduced in 2021, again in 2022, and it finally passed in 2023. It was introduced after six women of color were elected to DA positions, running on reform platforms. I don’t think it is any surprise that they pushed so hard for this legislation. It takes away people’s votes. It takes away people’s voices. Why should they be allowed to override thousands of people’s votes and remove an elected official? I’m not the status quo. I’m not what used to be in this office. I think people have a real problem when there’s [a] change of this magnitude.

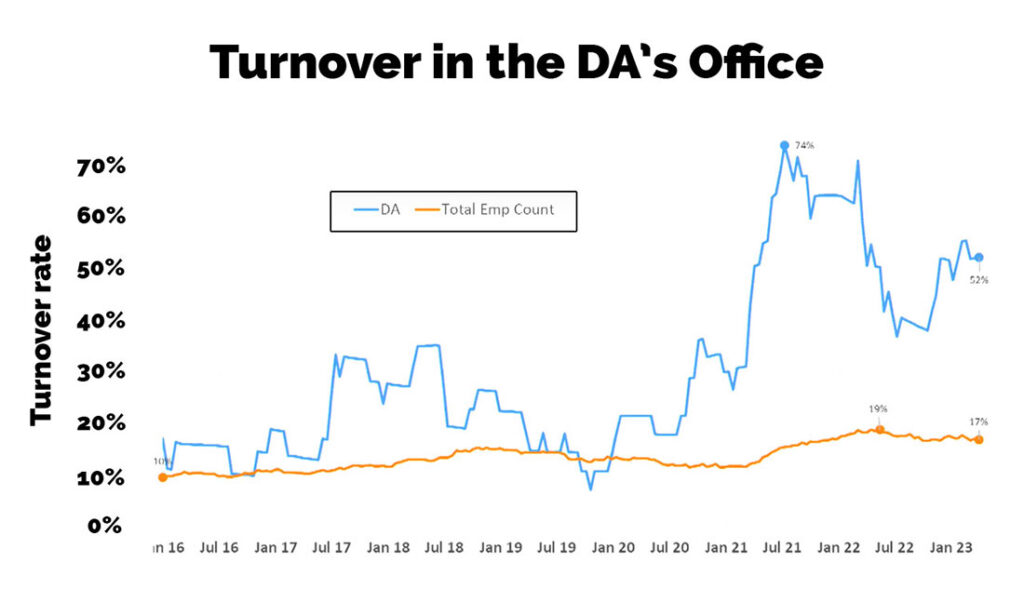

FP: But you’ve had 35 prosecutors resign in just two years, which is about a 100% turnover rate per year. Doesn’t that mean there is work in your office that’s not being done?

DG: When I took office in 2021, there were 14 DA offices across the state that changed leadership. When that happened, there were over 400 vacancies. Attorneys were moving from one circuit to another because leadership changed, and that’s normal. When Ken Mauldin became DA 23 years ago, he lost all the people he had in the office then because leadership changed.

Due to COVID, the courts had been closed for 18 months. I walked in on Day One with 2,400 cases backlogged. That’s a lot that needs to be dealt with. Eighteen months is hard to make up. And then last year, neighboring counties started offering [attorneys] a lot of money. Clayton County started offering graduates straight out of law school $105,000 a year. The starting salary in my office is $55,000 to $57,000. How are we competitive? [Editor’s note: Attorney positions advertised on the ACC website currently list salaries of $57,266–$78,969, based on experience.] So, a lot of people left because of better opportunities. The people who stayed had double the load and less money. Right now, my caseload is 773 cases. It’s overwhelming, and it’s not sustainable. Since January, I’ve hired five assistant district attorneys, but we still need more qualified people.

FP: But the judges of the Western Circuit even sent you a letter, saying that your office wasn’t doing the job adequately. Your performance has been criticized by the police and by victims. Is it fair to say that your office is in crisis?

DG: I wouldn’t say that we’re in crisis. We have very dedicated people here. We have all our victim advocates, we have all our investigators, we have all our admin staff. What we don’t have are lawyers. Every other section in my office is full, that’s why I don’t say we’re in crisis. We just need more lawyers.

I don’t think there’s any DA’s office that does everything 100% perfect. Did we make mistakes? Absolutely. But when you have the scrutiny that I’ve had, anything becomes magnified. Everything that’s happened in my office has happened in other offices, although they might not have been in the media spotlight. Just because people are criticizing and they’re loud, doesn’t mean they’re right.

FP: What is your plan to fix all the turmoil in your office?

DG: Some of it, I can’t control at all. I can’t control what the media says. I can’t control what this attorney [Kevin Epps] who is suing my office says. He exaggerates and can say whatever he wants. When I received that letter from the judges, I asked for a meeting. We went over everything point by point, and there was some misinformation they had, and we were able to clarify that. I don’t know if those judges would all sign off on the letter now. All we can do is take it day by day and make the best decisions we can with the limited resources we have.

FP: Is the commission going to fix the salary differential for prosecutors?

DG: They’re doing a market study, so I’m waiting to hear about that. They did do a cost of living adjustment. I did have one ADA [assistant district attorney] that I went back and asked for an above-entry hire, and I got close to $10,000 more so I could bring this ADA on board. They [the commission] have been helpful in the past one or two months. We could have prevented a lot of things if these steps were taken last year when I first brought this to their attention.

FP: How many prosecutors are you down right now?

DG: I’m down eight out of 16 total positions. We have three positions that are filled by apprentices right now; they’re taking the bar in July. But they do help.

FP: Let’s get back to that lawsuit where the writ of mandamus was filed against you. If you happen to lose, what’s at stake?

DG: A writ of mandamus is to ask a government official to do something very specific. But this lawsuit doesn’t say anything specific. If the prayer for relief is to tell me to do my job, so the court tells me to do my job? I’ve been doing my job from Day One. [The lawsuit] is unnecessary. It’s been a disruption to my office, from the overwhelming amount of open-records requests to the number of subpoenas out to five sitting judges and other government employees. This is not the right mechanism for their concerns. It’s political in nature. It’s an opportunity to sow doubt in the community with an election coming up.

FP: I also wanted to ask you about something public defender John Donnelly said at a recent Federation of Neighborhoods forum. He said that restorative justice is not in place in Clarke County courts, despite it being a plank of your campaign, because your office hasn’t followed through. Is he right about that?

DG: We don’t have an adult restorative justice program. We just got a juvenile restorative justice program up and running. These programs take money, they take staff, they take facilities. It took us six months to get an MOU [memorandum of understanding] through the ACC government between my office and the Georgia Conflict Center for [the juvenile restorative justice program]. It takes money to be able to run this. It takes a steering committee. It takes so long to put a program together that we need to make sure it works before we expand it to adults.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.