Winterville resident John Cooper has a regular need for timely ambulance responses, without which his son’s life would be in danger. James, his special-needs son, has epilepsy and suffers from seizures that are sometimes so severe that he stops breathing.

On July 9, 2019, Cooper pleaded with Athens-Clarke County commissioners by email that they do something to address some late emergency responses to his home. “James’ seizures present an extraordinary danger which requires immediate medical intervention beyond which can be given in our home. National EMS has responded to almost all of our calls within an unreasonable time period,” Cooper wrote.

Later that day, commissioners heard a presentation about National EMS given by Dee Burkett, executive director of patient services for Piedmont Athens Regional and chairman of ACC’s EMS Oversight Committee. Burkett defended National EMS during his presentation, fielding and answering most of the commission’s questions. These questions covered a range of topics and included several specific examples of slow ambulance response times as well as a lack of transparency surrounding the company generally.

After being questioned by Commissioner Patrick Davenport, Burkett seemed to refer to Cooper’s email and paint him as an unreliable witness. He reassured Davenport that National EMS double-checked their response times to Cooper’s home, finding that they were well within acceptable standards.

“The last three response times from dispatch to on-scene were six, nine and six minutes. It can seem like an eternity if you’re calling 911. Minutes can change character on you when you’re trying to get an ambulance to your place,” Burkett said.

As Cooper’s case brings to light, though, National EMS—a for-profit ambulance company that contracts with Piedmont and St. Mary’s—appears to have presented their emergency response times in a way which ignores the perspective of the patient and is inconsistent with their outsourcing agreement. This resulted in times being reported to the EMS Oversight Committee and the ACC Mayor and Commission that are minutes shorter than they would be otherwise.

When Does the Clock Start?

Cooper said that he was “infuriated” by Burkett’s answer. “At no point, on any call, could any conceivable case be made that someone came in six minutes. That’s absurd,” he said.

While admitting that he’s “not sitting there with a stopwatch,” Cooper says he keeps a log of his 911 calls, including the time of the call and the time the ambulance arrives on the scene. He insists that most of National’s response times are in the 15–20 minute range, not the six to nine minute range that Burkett claimed. He says that National EMS is “obfuscating” their real response times.

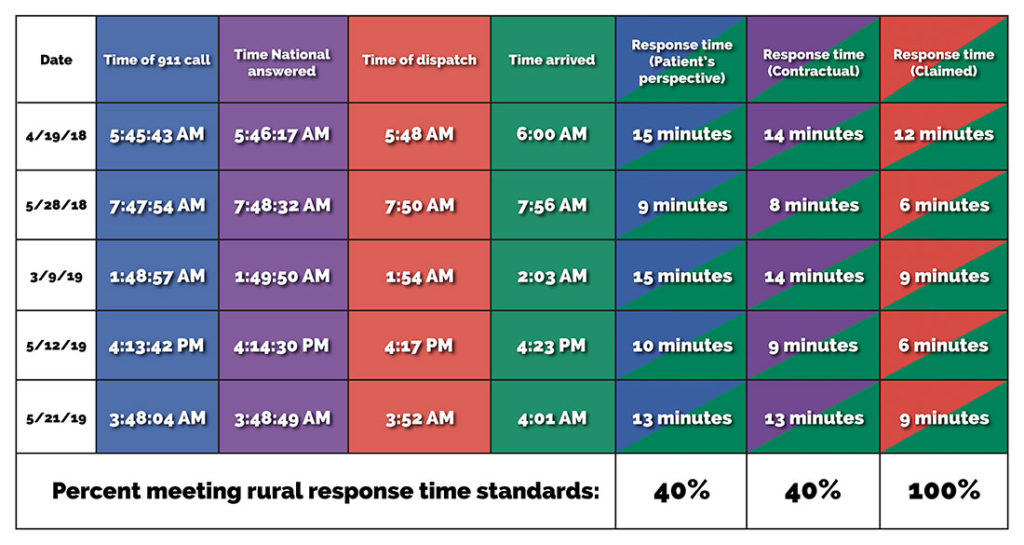

Athens Politics Nerd obtained a copy of an email that National EMS sent to the EMS Oversight Committee that included the times of five different EMS responses to Cooper’s home in 2018 and 2019. These response times ranged from six to 12 minutes, averaging out to 8.4 minutes.

If taken at face value, the times are good, considering that Winterville is somewhat distant from Athens’ city center (although National has an ambulance station only a few miles away). National’s outsourcing agreement with local hospitals allows a response time of up to 12 minutes and 59 seconds to respond in rural areas, so all of these calls would seem to fit under that standard—if Winterville is considered rural.

Public safety advocates Sam Rafal and Bob Gadd have criticized National EMS and the EMS Oversight Committee for claiming that Winterville’s population is low enough to justify the rural standard. They insist that the more stringent urban standard of under nine minutes should apply instead. The oversight committee uses the U.S. Census Bureau’s definition of rural (under 2,500 people) and urban, and Winterville does count as rural, according to that definition. Rafal and Gadd say that the census definition was not intended to be used for this purpose. The Census Bureau also classifies Athens-Clarke as an entirely urban county, and so do the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Another key point to consider is the time when National EMS started the clock, so to speak. According to Burkett, the clock was started “from dispatch” on these calls, and the email National sent to the oversight committee repeats this phrasing, using “unit dispatched” as the start time.

There is no national, binding standard around response times, and different agencies frequently use different starting points. “Many private and public agencies report only the times under their direct control as their response time, often excluding dispatch and mobilization time. Others report only travel time,” writes Jay Fitch in a Journal of Emergency Medical Services article. In his opinion, “the only correct way to measure a response time is from the patient’s perspective,” starting when the 911 call is first answered.

In their outsourcing agreement, National EMS is given a bit more leeway than it would have under Fitch’s strict definition. In the agreement, “response time” is defined as “beginning with National’s initial receipt of an emergency ambulance call… and ending when the ambulance arrives at the location.”

In Athens, 911 callers who request an ambulance have to report their emergency twice, once to the ACC 911 center and a second time to National EMS after being transferred. Starting the clock when National receives the call would add about 30–50 seconds to the response time from the patient’s perspective in most cases, according to data from the ACC 911 center.

While National EMS cannot be held accountable for an emergency call until it is made aware of it, tthere is a further delay between the time when National EMS picks up the phone and the time they are able to dispatch an ambulance. It appears from the outsourcing agreement that they should be held accountable for this time.

There is no mention of the “unit dispatched” timepoint in the definition of response time used in the outsourcing agreement. Using such a time would also not be consistent with the patient’s perspective on how long it takes for an ambulance to arrive.

Crucial Minutes

Three different definitions produce three different response times that could have been reported to the EMS Oversight Committee and to the mayor and commission. While being only minutes apart, the differences are enough to dramatically change National EMS’s record of adherence to response time standards.

As mentioned earlier, a generally accepted standard is that ambulances should arrive at a rural location in under 13 minutes. A tenth of responses may exceed this time, but the agency should arrive at no less than 90% of calls in under 13 minutes. National EMS meets the response time standard in all of the calls using Burkett’s definition of “response time,” but in only two of the five calls using either of the other definitions.

Don Cargile, community relations director for National EMS, told APN that National EMS starts the clock “once we have a location and a nature of the call,” seeming to indicate that it generally starts the clock sometime after a dispatcher picks up the phone, but not immediately. However, he asserted that they are following the definition as listed in their outsourcing agreement, but that their starting point is “sometimes… the same time that the unit is dispatched.” This could happen, for example, if the ambulance unit was already in motion at the time of the call.

The ACC Police Department has been requesting a consolidation of the ACC 911 center with National EMS’s dispatching center for years, and the commission finally agreed to this request in 2020. It may take a few years to bring full public control to 911 dispatching, but once the consolidation is finished, response times will presumably begin when 911 calls are first received.

This will bring the definition of response time in line with the patient’s perspective. The consolidation will also make all response time data available to the public. Currently, National EMS refuses to share its raw data, even with the mayor and commission.

“I don’t understand why National is so secretive about their response times,” Cooper said. “They are a private business. They need to be held accountable.”

While being critical of National’s response times, Cooper was clear that, overall, he values the quality of its work. “National does a fine job once they arrive,” he said. “The big issue is that it takes them too long to get here. I’m thankful for what they’re doing, but I want them to improve.”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.