While Georgia voters handed Democrats historic wins in the recent presidential and U.S. Senate elections, Republicans maintained their hold on state government and secured a once-in-a-decade prize: control over this year’s redistricting process that they will likely use to benefit GOP candidates for the next 10 years.

Georgia Democrats had worked for years to grow their ranks of voters in hopes of winning control of at least one chamber of the General Assembly and gaining leverage in redistricting plans. Ahead of the 2020 election, Democrats expressed confidence they could generate a blue wave that would allow them to pick up enough seats to flip control of the state House. But that effort fell far short. In the end, Democrats won just two of the 16 seats they needed in the House, with Republican legislative candidates receiving a flood of money from outside Georgia that helped propel them to victory.

The lead player in the effort to hold off the Democratic surge was the Republican State Leadership Committee, a tax-exempt political organization dedicated to electing Republicans to state offices and protecting GOP incumbents. The Washington, D.C.-based group spent more than $2 million on state House and Senate races in Georgia in 2020. As a central part of its campaign, the RSLC plowed more than $660,000 into a successful bid to unseat Democratic House Minority Leader Bob Trammell (D-Luthersville), campaign records show. The day after the election, as votes were still being counted, the RSLC issued a statement congratulating Republican legislative candidates for holding the line against Democrats’ efforts to turn Georgia blue and protecting the state’s citizens from “liberal gerrymandering after the next Census.”

While the RSLC played a lead role in helping Republicans maintain their hold on state government, other groups also made substantial contributions to the effort. In all, Republican-aligned state and national groups and state GOP leaders spent nearly $9.5 million in support of state GOP candidates in the 2020 election.

Democrats, by contrast, developed a far less robust system for financing state legislative candidates, focusing most of their effort instead on voter registration and turnout. National groups backing Democratic state candidates nationwide raised millions of dollars but spent relatively little in Georgia. Two of the biggest organizations, the Democratic National Redistricting Committee and the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, contributed just over $260,000 to Democratic efforts in Georgia.

“There’s no question that money, when you’re talking about a legislative race, can play an outsized role,” said Michael Li, senior counsel at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice. “There’s a huge national interest in the outcome of races in places that nobody has heard of. It’s not about the place or about the state. It’s about who controls redistricting.”

The Reward of Redistricting

With control over the redistricting process secured, Republicans will soon turn their attention to redrawing the boundaries of the state’s legislative and congressional voting districts, based on the results of the U.S. Census. Politicians can, and often do, use that power to craft districts that benefit their own party and its candidates, a tactic known as gerrymandering. Both Democrats and Republicans use the practice. In addition to further marginalizing minority parties, this use of redistricting for political gain is also widely seen as diluting citizens’ ability to hold elected officials accountable, increasing the number of noncompetitive races and spurring factionalization.

Republicans controlled the redistricting process in Georgia for the first time following the 2010 Census. By carefully drawing districts that included a majority of reliably Republian voters, the party was able to maintain its hold on state government for the rest of the decade. While shifting demographics and a concerted voter registration and turnout drive allowed Democrats to come close in several state House races in 2020, they were unable to overcome the Republican-drawn maps and the GOP-allied spending campaign.

Democrats now face the prospect of having to climb that hill all over again. Two U.S. Supreme Court decisions will add to the challenge. In 2013, the court invalidated a provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required Georgia and other jurisdictions with a history of discrimination against Black voters to obtain approval from the U.S. Justice Department before making changes to district boundaries. Elimination of the “preclearance” requirement means newly drawn maps can’t be challenged until after they are approved by the state. With the 2022 midterms approaching, elections could be held in districts that are under review by the courts.

Adding to the difficulties for Democrats, the Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that federal judges do not have the power to stop politicians from drawing electoral districts for political advantage. While legislatures cannot engage in racial gerrymandering, the court found that claims of maps being drawn for partisan advantage are “beyond the reach of the federal courts” and would have to be addressed in state systems.

While Republicans will have significant advantages in the redistricting process, they will also face real challenges. As the state’s demographics continue to shift in Democrats’ favor, Republicans will have to work harder to draw maps that favor them over the years.

“They see the trends coming,” said Charles Bullock, a professor of political science at the University of Georgia who studies redistricting. “I think Republicans will be more aggressive in trying to ensure that they can hold onto the state legislature. They can’t be sure of holding onto the governorship, but they could ensure their ability to hold onto the state legislature.”

The Republican Money Machine

The Republicans’ ability to maintain control of state government, and thus of the redistricting process, was due in large part to an extensive campaign-finance infrastructure that includes state and national PACs, independent committees and so-called “dark money” organizations that are not required to disclose their donors.

The cornerstone of that network is the RSLC. The group, founded in 2002, gained wide attention in 2010 for its Redistricting Majority Project (REDMAP) which sought to establish Republican majorities in state legislatures for the explicit purpose of redrawing maps to maintain Republican strongholds. The project was highly successful, helping Republicans gain full control over 11 state governments in 2010, allowing them to draw GOP-friendly legislative and congressional maps that remained for the next decade. The RSLC relaunched its REDMAP initiative in 2015, pledging to invest $125 million in the cause through 2022.

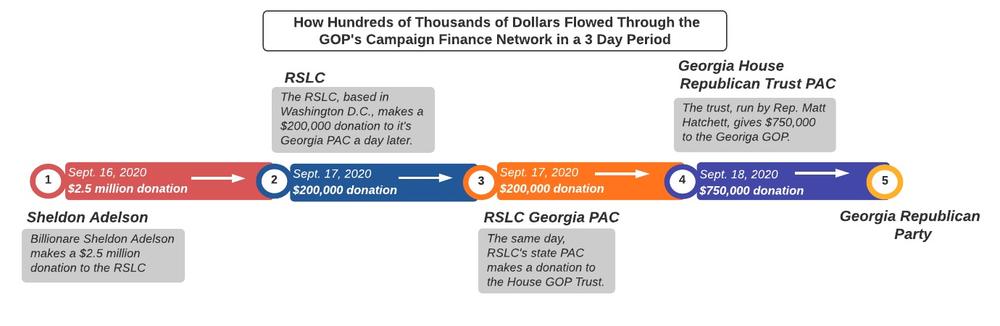

In 2020, the group donated almost $45 million to Republican efforts across 15 states. In Georgia, the RSLC contributed just over $2 million, divided between its state PAC and independent committee, according to campaign finance records. The money often travels a circuitous route through interlocking committees and campaign finance organizations. Between July and September 2020, for example, the RSLC made three contributions to its state PAC, totaling $425,000. This included a Sept. 17 donation of $200,000. The same day, the PAC made a $200,000 contribution to the Georgia House Republican Trust, a state PAC created to support GOP state House candidates. A day later, the trust made a $750,000 contribution to the Republican Party of Georgia.

In addition to the money from the RSLC, the trust took in more than $4.8 million before the 2020 election, receiving large donations from national Republican PACs and prominent Georgia business leaders. The trust, run by state House Majority Caucus Leader Rep. Matt Hatchett (R-Dublin), gave most of this money to the Republican Party of Georgia and made contributions to individual GOP candidates.

In all, RSLC’s state PAC contributed $709,000 to Republican candidates and groups in Georgia this cycle, up from $29,000 in 2018. RSLC’s state independent committee, which can spend on behalf of candidates but cannot contribute to them directly, spent $1.3 million in the 2020 cycle. The independent committee’s money went to digital, TV, text message and mail advertising in support of Republicans. Many digital ad payments went to IMGE, a suburban D.C.-based communications and consulting firm whose board of directors includes former RSLC and Republican National Committee chairman Ed Gillespie.

The RSLC made the defeat of Democratic House Minority Leader Trammell a priority, announcing in June that he was the committee’s “top target” in the nation. The RSLC’s independent committee financed a series of attack ads against Trammell, as well as a website that portrayed the three-term representative as “the Golden Boy of Georgia Liberals.” In October alone, the independent committee spent more than $141,000 on advertising in the race.

Trammell lost in November by 3 percentage points to political newcomer David Jenkins, the only Republican gain in the state House. Jenkins received the maximum $5,600 in contributions from RSLC’s state PAC for the primary and general elections, along with donations from the campaigns of other state House and Senate Republicans. Trammell raised $524,000 prior to the election.

The push to elect Republican candidates also received support from the RSLC’s “strategic partner” and “policy arm,” the State Government Leadership Foundation (SGLF). The foundation, headed by RSLC Executive Director Austin Chambers, is classified by the IRS as a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization, meaning it cannot directly collaborate with or donate to candidates. It can, however, advertise and “educate” voters about conservative policy issues and does not need to disclose its donors.

The SGLF announced it spent hundreds of thousands on digital and text advertisements highlighting 11 Republican Georgia legislative candidates “who demonstrated strong leadership” during the COVID-19 pandemic by voting in favor of cutting their own legislative salaries by 10% and offering tax incentives to companies that manufacture personal protective equipment. All of these candidates faced strong Democratic challenges, and two of them, Reps. Deborah Silcox (R-Sandy Springs) and Brett Harrell (R-Snellville), lost their seats, marking two of the three gains for Democrats.

“We were on offense,” SGLF Communications Director Stami Williams said. “It was our job to win state legislatures and that’s where we then pass the ball to the National Republican Redistricting Trust, and it’s their job to execute that other half with drawing maps.”

In January 2020, RSLC’s state PAC gave the maximum contributions to 20 Republican state legislative candidates in tight races, including three members of the House Legislative and Congressional Reapportionment Committee, Reps. Chuck Efstration (R-Dacula), Ed Setzler (R-Acworth) and committee chair Bonnie Rich (R-Suwanee). Rich, Efstration and Setzler won their races by narrow margins—Setzler by less than 300 votes. All had come within a few percentage points of losing their seats in 2018.

State GOP leadership was another major source of campaign money for Republican candidates. House Speaker David Ralston (R-Blue Ridge) and President pro tempore of the Senate Butch Miller (R-Gainesville) raised a combined $3 million prior to the election. They contributed more than half a million dollars to members of their caucus and Republican organizations. Advance Georgia, an independent committee created by Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan, spent $1.2 million on advertising for Republican state Senate candidates before the election.

The RSLC is classified by the IRS as a nonprofit political organization under Section 527 of the U.S. tax code. So-called 527 groups have no limits on how much they can receive in donations and no restrictions on who may contribute. They report their finances to the IRS rather than to the Federal Election Commission.

The RSLC’s largest donors include conservative interest groups, corporations and some of America’s wealthiest individuals. Sheldon Adelson, the recently deceased billionaire CEO of Las Vegas Sands Corporation and President Trump’s biggest donor, made a $2.5 million contribution to the RSLC on Sept. 16, 2020, one day before the organization disbursed $200,000 through Georgia’s Republican campaign finance network. Other large donors include the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which contributed $2.4 million in 2020, and billionaire hedge fund managers Paul Singer and Kenneth Griffin, who contributed $750,000 and $500,000, respectively. Significant donors from Georgia in 2020 include Waffle House, which donated $50,000, Georgia Power Co., which donated $27,500, and the chairman of Grady Memorial Hospital, Pete Correll, who donated $25,000.

Although the RSLC must disclose its donors, it receives donations from organizations that do not have to disclose theirs, obscuring the original source of some of RSLC’s funding. One of RSLC’s dark money donors is the Concord Fund, an alternative name for the Judicial Crisis Network, which advocates the appointment of conservative judges. The fund donated $675,000 to the RSLC in 2020. The SGLF, which like the Concord Fund is not required to disclose its donors, gave $2.5 million to the RSLC in 2020.

Little Money for Democratic Candidates

Democratic efforts to promote state candidates ahead of this year’s redistricting fell far short of the Republican campaign. In early 2020, national Democratic-aligned organizations said they were substantially expanding their financial backing of candidates in state legislative races, learning from the Republican efforts to win control of state governments in 2010.

The Democratic equivalent of RSLC, the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, pledged to invest $50 million into state legislative races in 2020. But IRS records show the DLCC spent little over half that amount nationally. The money spent in Georgia was far less; the DLCC gave a one-time $100,000 contribution to the Georgia Democratic Party in September, but records show it did not make any contributions to individual candidates, despite highlighting 22 of them in a press release.

The National Democratic Redistricting Committee, an organization chaired by former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, also outlined lofty goals of spending millions of dollars to retake state legislatures, but gave little in Georgia. The committee made two $50,000 contributions to the Georgia Democratic Party and gave $2,800 contributions to 22 state House candidates, totaling $167,000. The only candidate to whom the committee made the maximum allowable contribution of $5,600 was Democrat Kyle Rinaudo, the challenger to eight-term incumbent Ed Setzler, a House Legislative and Congressional Reapportionment Committee member. The 24-year-old Rinaudo lost to Setzler by just 280 votes.

The DLCC and NDRC did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The Georgia WIN List, a PAC dedicated to training and electing Democratic women across the state, raised $432,000 prior to the election but spent only $271,000. Almost all of the PAC’s funding came from hundreds of individual donors, most of whom only gave $100.

Fair Fight, a group formed by former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacy Abrams, raised and spent millions of dollars for the November general election and the January Senate runoff races. The group’s primary focus, however, is on voter mobilization and registration. Fair Fight’s campaign donations were distributed between races up and down the ballot across the nation, not just Georgia legislative races.

The lack of national investment in Georgia Democratic legislative candidates was largely the result of national organizations’ sense that the state was not competitive, said Adrienne White, vice chair of candidate recruitment for the Georgia Democratic party. That will change, White said, as a result of Democratic victories in Georgia in the presidential and senate races.

“I anticipate that resources that have previously been allocated to states like Ohio or maybe Florida, they’ll start sending that here because they see that our democratic ecosystem has rewritten the game on how to win,” White said.

But that investment may come too late for Democrats who will now campaign in new districts drawn by the Republican majority.

This story comes to Flagpole through a reporting partnership with GA Today, a non-profit newsroom focused on reporting in Georgia.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.