The nightriders were suddenly cloaked in the darkness that swept in as the moon fell behind the clouds. Alf had no idea how many there were. Twenty? Maybe more? They were said to move in groups as big as 30 or more. But in the near total darkness they were now innumerable, able to be anywhere. This was the terror of this new species of demon of the South, this Ku Klux Klan. They were everywhere and nowhere, killing at night and dissolving back into polite society during the day. The Klan, an “Invisible Empire,” hunted with impunity.

And now they’d found Alf Richardson.

He was still breathing heavily, having run now out past the edge of town. Alf looked down the dirt road one way, then the other. Nothing but impenetrable darkness. But he knew they were close. Then the clouds parted, revealing the moon, and against the darkness of the clearing now were seen the ghostly cones, bone-white and silent, appearing to glow in the moonlight. It looked like they’d split up to track him. Alf saw one slipping alongside the fence. Then he saw the pistol. Alf quickly pulled his own weapon and fired.

That’s when blasts rang out from men he hadn’t seen. Alf counted at least three or four guns firing on him. Most of the shots missed, but suddenly he was brought to the ground when metal shot ripped into his leg, as many as 20 shards tearing into the flesh of his thigh and hip. After the rush of gunfire subsided, the Klansmen dissolved back into the night, surely convinced that their rain of bullets had killed their victim.

They were wrong. Not only had their many bullets not brought down the despised Alf Richardson—the bootstrap black carpenter and businessman was back on his feet in just a few days—but the Klan terror would not dissuade Richardson from accepting re-election to the Georgia House of Representatives the next week, again joining fellow black legislator Madison Davis to form Clarke County’s all-black delegation in 1871. If the Republicans kept control, Richardson would even return to Atlanta with far more power than he’d had after the 1868 election, when he and 24 other black representatives were expelled from the statehouse for more than half of their two-year terms, until reinstated by congressional dictate from their allies in Washington. Furthermore, Richardson would travel to Atlanta to be a staunch defender of the most hated white man in the state of Georgia, Gov. Rufus Bullock.

The Life of Alfred Richardson

A slave until 1865, Alfred Richardson had wasted no time accomplishing the impossible, going from property to propertied in just a few short years. Born in 1832 into the American slave state at the beginning of its cotton explosion, his life would take a trajectory no one could have imagined. Early on, Richardson suffered the trauma of being sold away as a child to settle his slaver’s debts. At emancipation at war’s end, though, he was still only a county over from where he was born, residing in Watkinsville, then still in Clarke County.

By 1868, Alf’s carpentry afforded him seven acres in the western part of the county, just on the edge of Watkinsville, where he also ran a small saloon for fellow freedmen, what Athens’ Southern Banner derided as a “one horse doggery.” He soon went in with his brother on a small grocery. Richardson knew this made many whites angry, launching himself from slavery to ascendant property owner in the brief time since bondage; but that wasn’t what made him dangerous. It was Richardson’s rapid rise to political power that threatened white control and represented all that had been lost in the short time since the surrender at Appomattox.

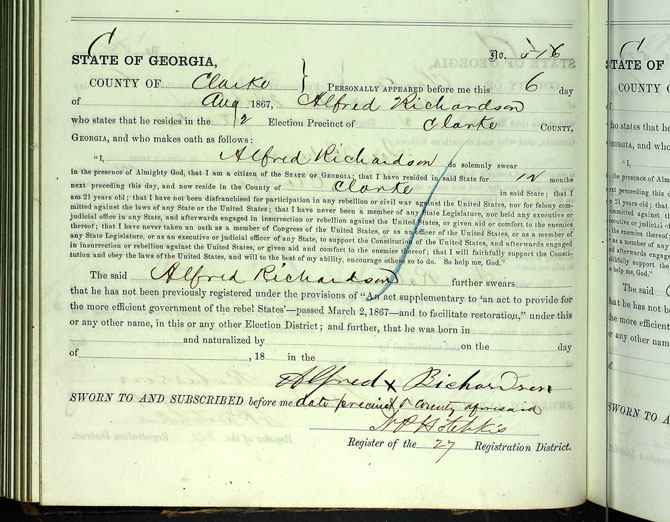

Richardson’s signature on a voter registry.

Elected in what Athens newspaper the Southern Watchman called the “bayonet election of 1868,” when Georgia was under federal occupation, Richardson came to embody for white Athenians the great shift in racial power that came with emancipation, especially in places like Clarke County, where a massive slave population meant that now freedmen outnumbered whites. On the eve of the election, the Southern Watchman warned that the election of black “radicals” like Richardson meant “black supremacy inaugurated.”

“Shall we have a White Man’s Government or be Ruled by Negroes?” worried a Watchman headline ahead of the election in April 1868. The paper, which boasted the largest readership in Athens, voiced the collective fears of racist whites who had seen, in just a few short years, Sherman rip his ashen path from Atlanta to the sea, the Confederate slave state fall, and black men get the vote. Georgia in 1868 was under military occupation by federal troops, a subdivision of the Third Military District, under the command of Gen. George Meade, infamous among former Confederates for defeating Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg. Meade, a sort of federal viceroy, commanded space in the pages of Athens newspapers to issue “orders” from “Military Headquarters.” For instance, white Athenians learned of the loathed Rufus Bullock’s official inauguration as governor in such an order, General Order No. 91, in which the “carpetbagger” Bullock was, in the end, installed under “instructions from the General-in-Chief of the Army” in Washington,” as carried out by “HEADQ’RS 3D MILITARY DISTRICT,” a place better known as “Atlanta” to occupied Georgians.

For almost a year after the passage of the Reconstruction Acts in Washington, federal forces established Athens as one of the military posts administering the occupation. Twelve northeast Georgia counties fell under the control of the 16th U.S. Infantry, stationed in Athens. Historian Robert Gamble explains that “the garrison’s purpose was to carry out the Reconstruction measures of the Republican Congress” in Athens and surrounding counties in the 3rd Military District. Major John J. Knox arrived with the occupation troops as the agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau, a division of the federal War Department, deploying the soldiers to carry out the first major directive from Washington: the registration of all black men of voting age. Then, the unthinkable: Federal troops in the familiar blue stood guard as men who’d worn the defeated grey lined up to vote among a larger crowd of new black voters. White fury dripped from the front pages of Athens newspapers. The Southern Banner issued a defiant charge to cast off the “despot’s heel” of the occupiers and their “alliance with negroes” and commence some manner of ethnic cleansing: “[W]e do sincerely believe that the State will be controlled by the negroes as certainly as through every white man in the State were disenfranchised… We believe also that the adoption of this hell-born conspiracy against the white race must result in violence and strife, if not the extermination of either the white or black race from the State… This portion of the State is to be the battle-ground.”

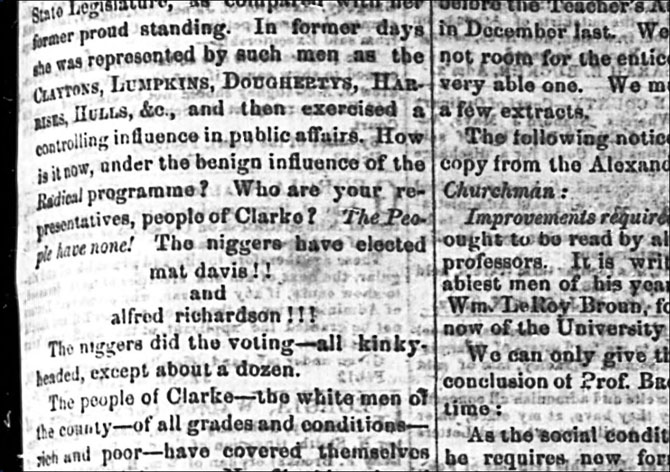

But the reality of losing a war to maintain a vast population of slaves meant that there were simply more black voters than white in Clarke County, and the occupying force ensured something close to a free and fair election. Thus, Clarke County found itself represented by black men in Atlanta. The men they’d recently owned now owned their seats in the capitol. The Southern Watchman seethed in the issue after the election. “Nothing better illustrates the humiliating condition to which the people of this once happy country have been reduced than the present representation of Clarke County in the state legislature,” began the raging column.

The paper vowed that such “villainy” would never be repeated.

Alf and Mat

Though considered an undifferentiated abomination in moments of rage, white Athenians would distinguish between their two representatives in calmer analysis. Madison (“Mat” or, sometimes, “Matt”) Davis was a light-skinned “mulatto” sometimes even passing as white. He was the less radical of the two and did much to assuage the fears of whites, in both demeanor and policy. Though Davis certainly caucused with the loathsome Republicans in Atlanta, he appears to have tended toward a more conservative legislative bent than his colleague. Davis, for instance, introduced a bill to repeal a prohibition on convict labor, the means by which tens of thousands of former slaves were returned to brutal forced labor in the decades after emancipation. Richardson, on the other hand, introduced a bill to regulate wages for the many new free laborers in the state. Black wage labor was now conducted via contracts that had to be approved by the Freedmen’s Bureau, but it appears Richardson sought additional state oversight to ensure fairness for former slaves seeking wages. Richardson appears to have joined the progressive wing of the black Radicals who sought the sorts of policies that would eventually be taken up by socialists and leftists, like the eight-hour workday, women’s suffrage and some of the public accommodations provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, nearly a century in the future.

This made Richardson far more dangerous in the eyes of Athens’ whites than his colleague Davis, who may also have been served by his slavery being under one of Athens’ prominent families, the Hodgsons, city carriage makers. Davis, a literate wheelwright whose forced labor did much to build the Hodgson family to its place of prominence, may have benefited from this fact in Athens’ white society. Davis would even be appointed Athens’ postmaster in 1882, one of the few freedmen to assume such a post in the state. It is also worth noting that when Richardson and 24 black representatives were expelled from the chamber in 1868, Davis was allowed to remain, perhaps due in part to a more congenial legislative manner. Davis was “conservative, sensible, and favored peace and order,” according to a white historian’s account.

Meanwhile, Athens historian Augustus Longstreet Hull wrote that Richardson “made himself extremely obnoxious to the white people” of Clarke County, “swelling with insolence and inciting other negroes to devilish deeds.” He was “a turbulent and dangerous negro, advocating violent measures against the whites,” according to another Athens historian’s account. Richardson may have belonged to one of the secret societies that coalesced into the Union League (or Loyal League) after the war, for he very quickly rose to prominence in the League, whose meeting hall on the edge of downtown formed the home base of his political rise. Contemporaneous and historical accounts by whites describe the Union League in terms of the occult, with meetings “characterized by dire oaths and frightful paraphernalia of skulls and cross-bones” that “exercised baleful influence among the negroes, urging them to lawlessness and violence.” The members were “summoned by the deep blast from a horn which reverberated through the still streets of the town in the evening hush.” The league appeared suddenly in 1867, when a “throng of negroes” proceeded to the meeting hall led by ”a negro man mounted on horseback, with sash and sword” and “brandishing swords and pistols, the negroes were sworn to vote the ticket,” meaning to vote Republican. While the league maintained some secrecy, by 1869 it was an established, mostly above-ground political organization, and the fearsome and even macabre descriptions by whites do more to reveal white fear of black political power than the character of the league.

The Union League’s growth and success in mobilizing black voting is what most directly led to the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan across the South, and in Athens. The Times and Messenger in Selma, AL urged white citizens to “organize a Ku-Klux Klan whenever they organize a league.” The Mobile Register suggested forming “Ku Klux clubs” and that “the first object of these clubs should be a persevering and systematic movement to break up the ‘Loyal Leagues.’” In Athens, the sudden rise of the Union League was matched by the emergence of the Klan. A later account by a Klan-sympathetic historian declared that in Athens “the Ku Klux kept [the Union League] in wholesome restraint.”

By December 1867, both white and black communities in Athens were more organized and prepared for violent conflict. That month, a group of college boys assaulted a black man in the post office, accusing him of “insolence,” an act that found retaliation that night, when two white men were hit with brickbats. On the night of Dec. 10, a group of around 100 black men organized and, armed with pistols, knives and clubs, took to the streets. Only the intervention of federal troops garrisoned in Athens prevented what might have been a small war downtown. Troops took command of the city streets that night and the next, and widespread bloodshed was avoided. But white violence would continue. Reports of murders and beatings grew in number, and with the start of the new year, the momentous election of April 1868 approaching, the incipient Klan began to challenge black voting with white terror. “From January on,” writes Robert Gamble, “there was vigorous activity among the whites to organize a militant conservatlve group” to oppose black political participation.

In Elberton, “pistols were drawn on negroes” during the four days of the election, according to Amos Akerman, a white lawyer in northeast Georgia at the time. Akerman, who would later become U.S. attorney general, described the Elberton “election” in a dispatch: “During the election there was a reign of lawlessness,” and “the negroes were utterly cowed” by white forces. He explained that hundreds of black voters abstained from voting in fear. In Athens, however, the threat of white violence was not enough to keep black voters from sending Richardson to represent Clarke County in Atlanta, alongside another freed slave. But the victory shook whites to the core, and the Klan exploded in Athens and across the state as 33 black representatives and senators traveled to join Gov. Bullock’s “Radical” outrage in the capital. By early June, the Southern Watchman reported optimistically that, in response, “the Ku Klux Klan is on a rampage” across Northeast Georgia.

Terror Spreads

The shocked fury of white conservatives continued to grow, and by September 1868, a little more than a month after they’d been seated in the Georgia General Assembly, all but four of the black legislators were expelled from the body. The Ku Klux Klan’s reign of terror began to permeate the entire state. Reports of violence, intimidation and murder began to come out of virtually all surrounding and nearby counties. A black school teacher in Lexington was terrorized, his school burned to the ground. Another Lexington man begged the governor for full “Military Rule with Garrisons at every county seat in this part of the state.” In Greene County, a black legislator would be viciously beaten by 65 Klansmen. White Republicans, few as they were in this part of the state, were not safe. The Klan in Walton County attacked a white woman because of her father’s Union loyalty. In Jefferson County, the Klan terrorized white Republican legislator Benjamin Ayer, who was exiled in Atlanta after the attack, unable to come home. He and nine other white Republican lawmakers in the same danger wrote a letter to Congress in early January 1869 begging for protection. Ayer would be murdered in Jefferson County in May. A white Republican senator, Warren County’s Joseph Adkins, would be brutally murdered that month, too.

Klan violence continued to terrorize black Georgians throughout 1869. Most attacks went unreported, and Richardson estimated that whippings, at least, occurred weekly in the region. Increasingly desperate pleas to the governor and to Republicans in Washington continued, and Gov. Bullock and some of the expelled black legislators travelled to Washington to make their case in person. Even Bullock worried that he’d be “‘Ku-Kluxed’ by a mob.”

Local newspapers railed against Athens’ election of two black state representatives during Reconstruction.

The appeals in Washington by Bullock and black legislators resulted in a December 1869 sweeping ruling by congress that Georgia be remanded to even harsher military control, with Major Gen. Alfred Terry installed to effectively preside over the Georgia government (at Bullock’s request) and forming a three-man panel of military officers to decide who should be seated in the legislature in Atlanta. The military overseers judged that Richardson and all black legislators be restored to the seats they’d won nearly two years before and, furthermore, that two dozen white conservative members be removed due to their prior loyalty to the rebel Confederacy. With Richardson and his black colleagues restored and the deposed Democrats replaced by their Republican runners-up, Bullock now had full Republican control. This is when the radical black wing of the party sought their juggernaut government, attempting, at the time, almost revolutionary innovations like women’s suffrage and a state police force to give muscle to Republican control and be an armed phalanx against white terrorism. It was an unthinkable outrage to the white conservatives, and the terrorist wing of the Democratic Party roared.

By the elections in the fall of 1870, Klan attacks—or “outrages,” as they came to be called—continued to spread terror, with the white conservative power structure tacitly, when not explicitly, lending aid. All the way up to the Atlanta Constitution, the conservative press began its role of aider and abettor of the growing terrorist threat in earnest. The Atlanta Constitution exemplified the tactic in 1870, implying that the increasing attacks were fabricated in its sardonic “Wanted—Ku Klux Outrages”: “They must be as ferocious and bloodthirsty as possible. No regard need be paid to truth.” There began in the Georgia press, and in Athens specifically, a sort of dance the conservative press performed, whereby Klan violence was at times celebrated and given its necessary widespread announcement (terrorism only works within a media that communicates the terror) but also strategically doubted. John Christy, the overtly racist publisher of Athens’ Southern Watchman, would soon travel to Washington to testify before a committee investigating the Klan, “There never has been any organization in the State of Georgia known as the Ku-Klux, or any other sort of secret organization, except the Loyal League.”

Richardson counted about two attacks per week in Clarke County during this time, mostly brutal whippings. Others were murders or attempts, like the one on Richardson’s life in December. The terrorism was in pursuit of two goals: to frighten black voters from participation and to coerce labor to return to something like slavery. Richardson defied whites on both counts, rising as a black politician and achieving enough wealth to keep his wife and children off of white plantations. Former white slavers found their plantations failing when freed black parents managed to exempt their children, and sometimes wives, from field work. Under the slavery regime, entire familes were made to work, young children beside men and women. Farm productivity was predicated on this violent coercion of women and children, and all evidence points to Richardson’s wife and three children all escaping the workforce of wealthy whites.

Richardson was surprised when James Thrasher, a wealthy white man, visited him a few weeks after the Ku Klux attack attack. Thrasher had been asked by local Klansmen to join their ranks, but he’d refused. And now he was risking some danger by warning Alf of their plans. “Keep your eyes open,” the white man warned. “They are after you.” The sun went down as Thrasher told Alf everything he knew. “They say you can control the colored votes,” he continued. “They say you are making too much money. They do not allow any nigger to rise that way.” There was no more dangerous man in Clarke County than Alf Richardson. Across Georgia and all of the former Confederacy there were few men who so challenged the rule of white supremacy. Thrasher delivered the news: “They intend to kill you.”

The KKK Attacks

At midnight that night, the thunder of men battering the door shook the house. Fearing the worst, Alf had barred the door with boards, and eight or 10 men were acting as a human battering ram. Another 15 or so men waited behind them. When the men couldn’t break down the reinforced door a man emerged with an axe and began slashing into it. Alf watched from the inside as his carefully barricaded door was methodically torn through by the axe, the Klan torches’ firelight from the front porch visible more and more through the widening gash. They were going to make it in. He ran up the stairs and decided to fire at them from the top of the steps. But they were soon inside spraying gunfire, too many of them rushing up the stairs, and Alf abandoned his position again further into the house. He thought he might make it to the cramped garret at the top of the house where he had some more guns stashed. The house filled with Klansmen.

Meanwhile, Alf’s wife reached a window upstairs, opened it and screamed desperately for help into the cold mid-January night. Gunmen below sprayed the window with bullets, sinking about fifteen into the wood, but somehow missing Mrs. Richardson. Others, seeing the open window, called out that Alf had come out through the window, either up onto the roof or down to escape. They emptied the house and returned outside to find him. Alf, however, was still hidden away in the dark garret, just under the roof. A small opening, just big enough for one man to sneak through kept Alf hidden in what he called the “cuddy.” If the Klansmen could be convinced that Alf had left through the window during the commotion, they might leave and take to the surrounding area to track him down, like before. Alf and his family could easily abscond in the dark once the men turned their attention away from the house.

Silence returned to the second floor after the rush of men descended downstairs and outside. In the dark at the top of the stairs the man who remained must have seemed like a ghost, a white shape against the dark, still and silent in the hush. It’s doubtful that Alf knew that a man had stealthily remained in the dark upstairs. There was one place left to look for Richardson, and the small opening of the garret was soon filled with the blank white of masked face and hood. “I’ve got you,” said the mask.

A shot ripped into Alf’s arm. Then two entered near his ribcage. The shooter yelled down to his compatriots, “Come back up! I’ve shot him! Let’s finish him!” Alf felt a deep weakness come on as the blood drained from his body. The Klansman joined the others rushing back into the house. Alf dragged himself out of the tiny compartment and got himself to the top of stairs just ahead of the hooded group and just in time to fire at the man reaching the top. The man collapsed into a mound of bloodied white cotton, dead. The Klansmen fled. Alf, though quite wounded, survived.

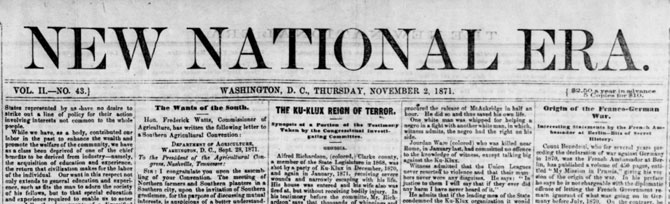

Frederick Douglass’ newspaper in Washington, D.C. celebrated Alf’s victory in the nation’s capital. What the account missed in accuracy it made up for in glee.

“Alfred Richardson, colored Representative in the Legislature, who lives in Watkinsville, was visited a few nights ago by Georgia’s chivalry, and after they had surrounded the house, like pure cowards, began to shoot into it. Three shots are said to have taken effect upon Richardson. Thinking they had finished their victim, they entered the house for the purpose of applying the torch, but the leader was saluted with a discharge from a shot-gun, which settled his account right there. The balance of the gang fled, carrying off their dead comrade. Richardson is not seriously wounded, and will soon recover. If the negroes of the South would, in all cases, defend themselves in this manner, there would be less fun in Ku-Kluxing, and fewer Ku-Klux.”

Even in sparse white Republican strongholds in upcountry Northwest Georgia, the Calhoun Times celebrated the Klan killer of Clarke County to its almost entirely white readership:

“Alfred Richardson, of Watkinsville, trumped the Ku-Klux the other night. A party of unknown men visited his house and commenced firing, whereupon Alfred concealed himself. One of the Ku-Kluxes then entered the house with a light, but at a signal from Alfred’s shot gun, he died promptly. This disgusted the party and they withdrew. Alfred carries three pistol balls under his side as trophies of victory.”

The governor, deploying his journalistic eminent domain, soon wrested space in Athens newspapers to issue a proclamation announcing that “a party of disguised men, known as the Ku Klux Klan, about thirty in number, went to the house of Hon. Alfred Richardson,” this being “the second attempt to assassinate the said Richardson.” In Athens, as elsewhere in the state, “the authorities of the said county of Clarke have failed to ferret out or to secure the apprehension of the perpetrators,” and so Governor Bullock and state and federal authorities were “offering a reward of FIVE THOUSAND DOLLARS for the apprehension, arrest and conviction” of the Klansmen and a considerable bounty of “one thousand dollars each for any additional number more than one of the ‘Klan’ engaged in committing the outrage.” A resident of the area stood to make a small fortune by cooperating with Bullock. No Klansman was brought to justice.

Alf on the Run

The Klan terror army, at work everywhere in the state, was operating now with virtually no resistance. Alf fled to Atlanta initially to avoid death, then to Athens, where relative safety could be found in denser black populations. Alf, his wife and three daughters likely sought refuge in the large black neighborhood of Lickskillet, where census records show the Richardsons living later. Athens and Lickskillet would not ensure total safety, but remaining in Watkinsville meant certain death. Alf would soon put the Watkinsville property up for sale.

It is impossible to know whether Richardson and his family were understood to be home in Watkinsville when the house was set ablaze by incendiaries weeks later. When it was initially reported in the Banner, writers and editors there could only speculate as to the Richardsons’ whereabouts. It was believed that the home invasion in January would have resulted in an inferno had Alf not repelled the attackers, so the successful firebombing weeks later may have been another attempt to kill Alf and his family. It could just as well have been an attempt to make the property worthless, as all of Alf’s structures listed for sale were torched torched: “a good frame house with seven rooms, a kitchen, a two-story smoke-house, a dairy,” as well as a blacksmith shop, all apparently burned.

Alfred Richardson and his family were, for the moment, safe in Athens, but the property was languishing on the market, gashed with the black scars from Klan arsonists. Nearly the full length of his body bore the wounds from his war with the Klan, with two metal balls now permanently embedded in his side as a reminder. He was a living witness to the ongoing terrorist takeover of the South. But that takeover was just then meeting with federal power, as Congress debated a sweeping “Ku-Klux bill,” the Third Enforcement Act, that would hand unprecedented power to the president to make war on the Klan. Athenians joined the rest of the white South in watching in horror as Congress moved to give the dreaded Ulysses S. Grant, now president, and his top army commander, the infernal Gen.l Sherman, the power to operate at will wherever the Klan reigned. According to the bill under discussion, the writ of habeas corpus could be suspended, and Grant and Sherman could deploy federal troops as law enforcement. It was what we’d call now “counterinsurgency,” a targeted war against the vast terrorist network of the South. Sherman went before the Senate to declare that “In 11 Southern states the public condition at the present time is one of unparalleled horror and anarchy.” Only a war against the Klan could reverse the tide.

Covering Up the Klan

The Klan had been central in the success of beating back black freedom and returning white supremacist control. “The Klan was a military force serving the interests of the Democratic Party, the planter class, and all those who desired the restoration of white supremacy,” writes Eric Foner, preeminent historian of Reconstruction. This was the realization Athenians were having as the Klan’s violent elimination was being debated in Washington. Say what you will about it, the Klan’s terrorism was working. Athens was an increasingly rare outlier in this regard, though. Richardson and Davis would be returning to Atlanta to represent Athens, despite the best efforts of the Klan, but the black vote was viciously suppressed elsewhere, handing full control of the legislature to the white Democrats. The Democrats would expel Bullock from office on spurious charges, with Bullock fleeing the state in fear of terrorist violence. The Klan hadn’t previously been uniformly beloved by whites, but white Athenians suddenly understood that the Klan paramilitary was, in the end, the only real force there had been to oppose black freedom after the war. And that realization during the course of 1871’s anti-Klan activity in Washington led to a remarkable warming toward the Klan by white Athens. As swiftly as the bill made its way to President Grant’s eager pen, so too did amnesia sweep suddenly over Athens and the South. Klan? What Klan?

A great charade began, with white Southern conservatives beginning a collective performance of sudden ignorance of Klan terrorism. The Augusta Chronicle, for example, had welcomed the Klan ahead of the “Bayonet election” in 1868: “Klan has been organized in this place…Success say we to the Ku Klux Klan!” But by the time the Klan bill was being deliberated in Washington in early 1871, a sibling Augusta paper would call the existence of the Klan “an unmitigated lie” and that “if such a body existed, it was among the Radicals.” The Chronicle, champion of Klan salvation three years before, now vociferously denied in 1871 the charges of Klan violence. “Many of the alleged outrages are manufactured in the North,” bellowed the paper in April and that, instead, “The people are robbed, plundered and insulted by negroes.”

In March, just two weeks after reporting the Richardson fire as a white attack, the Southern Banner announced that “the burning of Alf Richardson’s property was not the work of the horrible Ku Klux after all.” It was “a negro” who set the fires, reported the Banner, and furthermore, the initial attack the previous fall was Richardson’s fault for interfering in some matter having to do with a “stolen heifer.” The cow was stolen by “a negro,” as well. These were, in the end, problems with black people, the paper now concluded. “It has not been a political persecution of Richardson—and there is no evidence of any hostile intent towards him at the outset,” became the new line, echoed by the Watchman. Richardson, explained the Watchman, was in fact “the aggressor in the first instance, and this unwarranted act of his led to the difficulty which occurred afterwards.” When the violence couldn’t be attributed to black culprits, white Athens decided that Richardson’s own flaws and deficiencies were to blame. It was Richardson’s own fault, now claimed the Banner: “Those who are familiar with all the facts concerning Richardson’s troubles attribute them more to his own rashness and folly than to any political cause.”

Both Athens papers became obsessive in their opposition to the anti-Klan activity in Washington. If the Klan was the paramilitary wing of the Democratic Party, Southern newspapers like Athens’ Banner and Watchman became the propaganda organ of the same white supremacist machine. The “monstrously iniquitous” Ku-Klux bill “destroys liberty and establishes a military despotism,” railed the Southern Banner as the bill was debated during the spring of 1871. The Banner that same week turned over its entire editorial space, much of the paper in those days, to the Democrats’ address in Washington against “the abominable Ku-Klux bill.” Simultaneously, the Watchman reported on “the so-called Ku-Klux bill,” claiming that “since the foundation of the world there has not been a more shameless, vile and devilish fraud, cheat and swindle attempted.” The Watchman now described the Klan as a “myth” concocted by Republicans in Washington to bring war again to the South. The “dangerous powers committed to General Grant by the Ku-Klux bill…in effect make him a Dictator,” the Watchman seethed. The paper quoted John Quincy Adams II, scion of the mighty American political family, who declared that “Ku Klux bill declared war” on the South. In an unprecedented move, the Watchman in May devoted the entire front page to printing the text of the newly signed Ku-Klux law. Many in the South prepared for a return to war.

Mr. Richardson Goes to Washington

Alf stepped right into the maelstrom of anger and fear. “A Clarke County Negro Before the Ku-Klux Committee,” ran a Watchman headline in July. “A Washington telegram states that Albert Richardson…had been before the Ku-Klux Committee. This is evidently intended for Alfred Richardson,” the paper informed white Athenians. Richardson had traveled to Washington, the very belly of the beast, and testified to his travails at the hands of white Athenians. The Watchman dutifully disputed Richardson’s sworn testimony in Washington with their new story wherein Alf “was the aggressor, the whites the principal sufferers.” Richardson’s explanation that he’d abandoned his land and moved into town for safety, like so many other rural freedmen fleeing violence, was refuted with the claim that “lazy negroes…avail themselves of this excuse for going to town to live by stealing.” There is no Klan to speak of, went the new refrain, with a chilling wink at the article’s conclusion: “Alfred Richardson knows as well as we do that no negro who behaves himself properly has any reason whatever to fear violent treatment at the hands of any man in our county.” There is no Klan, but it is precisely men like Richardson for whom there’d be a reason to have one. Richardson, who gave the first testimony of Georgians before the committee, did not tell only of his own nightmare. He explained that “not a week passes” without a night attack, usually a beating, of black men, women and even children. Alf named names, under oath and on the record. His testimony read like a rap sheet, an indictment of white Clarke County.

The white performance of ignorance and amnesia continued apace. One of white Athens’ most esteemed citizens, Watchman publisher and popular congressional candidate John Cristy, traveled to Washington to deliver testimony to negate Richardon’s. There is only “the impression among the negroes that there is really a Ku-Klux organization,” Christy told the committee. At worst, bands of disguised men issued the rare attack for “fornication and adultery,” Christy explained, but “I know of no man having been punished for his politics.” Christy repeated that the first attack on Richardson was Richardson’s fault and that the second attack was not, as far as Christy was concerned, verifiable. The third attack, the arson was, again, a black man’s fault. Nothing about Richardson’s politics or position had anything to do with his misfortune, Christy told the committee. Christy was echoed by voices like that of Thomas Hardeman, a conservative white state representative from Macon, who claimed to the committee that he knew nothing of a Ku Klux Klan and that “whites, instead of the blacks, were kept from the polls by intimidation, the negroes having taken possession of the polls.” The testimonies came at a time, after the election of 1870 and before the ouster of Bullock in October 1871, that saw much of Georgia’s black electorate terrorized into abstaining and white supremacist Democratic rule returning. With straight faces, white conservatives told Congress the opposite was happening.

Federal anti-Klan power moved south into Georgia. “Martial Law for the Whole South,” ran a headline in the Watchman. Just weeks after Bullock resigned and fled the state due to what he called “political conspirators who seek the overthrow” of the government, federal troops moved into Clarke’s neighbor Jackson County to battle Klan forces there. A number of alleged Klan members—or ”innocent young men,” according to the Watchman—were rounded up by federal forces in October. Whites in the county retaliated against the federal marshals, and soon two detachments of federal troops took the county seat of Jefferson. The whole affair was, according to the Watchman, only “a vile attempt to make a Ku-Klux outrage,” a strategic provocation. Indeed, the whites of Jackson County fulfilled their end of the alleged federal ruse and a Ku Klux militia fired on the troops, who returned fire. The “bullets riddled the tents of the troops,” according to reports, and the two detachments of troops remained in Jefferson through Christmas to suppress the Klan.

The Southern Banner, now actively operating as Klan propagandist, attributed accounts of Klan attacks on troops in Jackson County as “a put up job” to “get martial law declared in Georgia.” The Watchman had recently warned frantically, “Telegrams from Washington express the opinion that martial law will be declared by the President, throughout all the Southern States, in a short while.” It was only the “ostensible purpose” of the troop presence in Jackson to protect against the Klan, purported the Banner. The real purpose of the “grave wrongs that have been heaped upon” white residents was to fabricate the conditions for a second invasion of the old Confederacy. The paper in Walton County, where Alf had been born into slavery, warned that “under the pretense of suppressing disorder, which does not exist, [Republicans] set the President about the Constitution, giving him the powers of a military dictator.” The Augusta Chronicle declared that the anti-Klan actions by Republican-controlled Washington marked the “inauguration of actual war against the Southern States.” President Grant’s Secretary of War warned in December that “an armed rebellion of regular organization and great strength now exists” in the South and vowed, with a sizable portion of the US army, to assist freedmen and Republican allies in the South in “putting down this second rebellion.” Many in the South prepared for war against Republicans as 1871 came to a close.

How Did Alf Die?

“We have heard with regret of the death of the Honorable Alfred Richardson, a member of this House.” It was just weeks later, January 11, 1872. Madison Davis stood solemnly before the Georgia House and offered a resolution of mourning to “the memory of the deceased.” White conservatives who now controlled the body approved the measure with a distinct lack of sorrow, or “without much enthusiastic regret on the part of the white members,” as reported by the Augusta Chronicle. White conservatives were glad to see Richardson gone. His seat would soon go up for election at a time when the continuing violence and intimidation was finally bringing Athens in line with much of the rest of the state. Alf wagered that not 20 black men out of 1,000 would vote in Clarke County in the 1872 election. He wouldn’t live to see how right he was. After two elections bringing black men to office, the black vote in Clarke County would be successfully suppressed in 1872, and a white conservative would replace Alf Richardson in Atlanta in a special election. Later in 1872, Madison Davis would suddenly and without explanation withdraw his name from the ballot, and a white man would claim that seat as well. “Negro representation is a thing of the past in… Old Clarke,” celebrated the North-East Georgian. After Richardson and 31 black Republicans entered the General Assembly four years earlier, only four black members would remain—soon, none. Clarke County would not send another black man to the state government for well over a century. An apartheid regime, backed and enforced by waves of terroristic violence, would settle over the South for the next hundred years.

“Clarke County sent two negroes to the Legislature, Madison Davis and Alf Richardson,” wrote Sylvanus Morris in his History of Athens and Clarke County. “The former was conservative, sensible, and favored peace and order… Alf Richardson was a turbulent and dangerous negro, advocating violent measures against the whites. The Ku Klux killed him in his house.” Morris, then dean of the law school, was building on Augustus Longstreet Hull’s canonical history of Athens, Annals of Athens, 1801-1901. Hull’s account also describes the Klan’s murder of Richardson, a story further enriched by the author’s personal connection to the members. “In Clarke County the Ku Klux comprised some of whom are now living in Athens and are well known to the writer,” wrote Hull, the preeminent chronicler of Athens during the 19th Century. It seems as though the story of Richardson’s murder comes to the reader a short distance, from Hull’s ear to his pen.

Morris’ account is corroborated by Hull’s, in which Richardson’s threatening character invited the violence. According to Hull, Richardson was killed by the Klan because he “had made himself extremely obnoxious to the white people, swelling with insolence and inciting other negroes to devilish deeds.” These later accounts, written by whites, echo what black House leader Henry Turner said at the time, that “any man who is a leader” or “who is thought to be a center of influence, every such man, in many of the counties, they are determined to kill out. They will kill out all they can kill.” That determination could be witnessed in Clarke County, whose official history told of a defiant black leader hunted until he was destroyed.

Then the story changed. In the latest telling of this history. In Michael Thurmond’s 2019 reissue of his A Story Untold: Black Men & Women in Athens History, Richardson does not die by Klan hands. An alternate history developed sometime in the wake of Hull and Morris’ canon, and Richardson’s death came to be understood as due to natural causes. Beginning after the mid-20th Century, this became the new account of Alf Richardson’s death, despite the lasting esteem afforded the work of Morris and Hull. Hull’s Annals of Athens remains the “foundation for modern historians and researchers of Athens’s rich nineteenth-century history,” according to the Athens Historical Society, which in 2015 created the Augustus Longstreet Hull Award for exemplars of dedication to Athens history. Though disputed eventually by the more recent histories, Hull’s account is fortified by what he describes as social connection to Klan members. Hull, a prominent Athenian, describes a thorough relationship between the Klan and the Athens elite, like the Hull family: The Klan was “aided and abetted by older men of character and means, members of the various churches and esteemed for their worth.”

Sylvanus Morris’ account, though issued later than Hull’s, may be considered even more credible than Hull’s in how it’s delivered from the topmost turret of the university’s ivory tower. Morris, himself the renowned dean of the law school, published his history under the aegis of a board of editors whose names would eventually be printed on prominent street signs and carved into university granite. University Chancellor David Barrow led the distinguished editorial board comprised of deans, professors, a state representative and the historian general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. With its imprimatur of the university elite, Morris’ record of Athens’ Klan has the group killing Richardson and, more broadly, destroying the Union League and its aims, “kept in wholesome restraint” by the terrorists. Klan terrorists, in other words, inaugurated the apartheid rule under which the Morris and Hull accounts were issued and were celebrated for it.

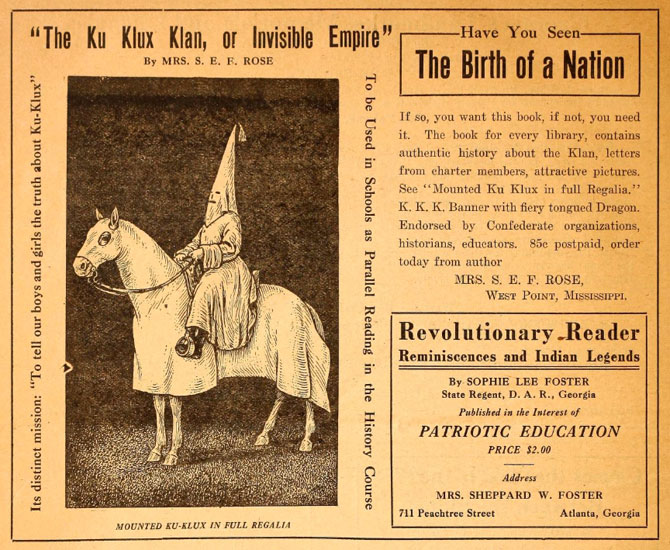

Both the Hull and the Morris accounts are, one soon realizes, those of Klan sympathizers, if not active advocates. Just after publishing his Annals of Athens, Hull would publicly announce that lynching is “sometimes condoned.” Morris and his board of editors, publishing their history in 1923, during the heyday of the resurgent “Second Klan,” appear swept up in the era’s Klan apologia. The Klan’s second wave during the 1920s led to hundreds of respected Athens men joining the order, from police and politicians to preachers and professors. Many women joined the effort in auxiliary roles. The inclusion on the board of Mildred Rutherford, the national historian of the Daughters of the Confederacy who said a few years earlier that the Ku Klux Klan “was an absolute necessity at the time,” speaks to an explicit pro-Klan sympathy in the group of editors. Rutherford would even issue publications with pro-Klan advertisements. Regardless of how Richardson died, it became a propaganda victory to claim his murder, much like ISIS or al Qaeda might claim an independent attack to accrue power. It was figures like Hull and Morris and his board of editors who found themselves in possession of the power to create the official history of Athens.

Influential editor and historian Mildred Rutherford routinely featured advertisements for the KKK in her publications.

The story of Alfred Richardson becomes something of a murder mystery; not a question of who committed a murder, but whether there was one at all. Was Alfred Richardson killed, or did his murder come after the fact? Can you be murdered after you’re dead?

The surviving documentary record is scant, but two newspaper accounts do remain. It’s the only place we find positive evidence to counter the narrative of Richardson being killed. In fact, only one of the two newspaper reports gives us a precise and explicit piece of contradicting evidence. An uncharacteristically terse reference to Richardson can be found buried in the Jan. 12, 1872 issue of the Southern Banner: “Death of a Legislator — Alfred Richardson, representative of Clarke County in the Legislature, died at his residence in Athens on Tuesday, of pneumonia.” The Watchman’s headline that week is even more emotionless: “A Vacancy,” runs the top line in small print above their vague report: “Alfred Richardson, one of the colored Representatives in the Legislature from this county, having died here one day last week, a vacancy has been created, to fill which the Governor will no doubt, at the proper time, order an election.”

Do we believe the Southern Banner? It was January when Alf died—that we do know—when pneumonia would be most likely to threaten. This was also 1872, before the advent of modern medicine. Pneumonia was one of the leading causes of death during the period, sometimes the principal killer. But Alf was only 35 years old, and by all indications he was in good health. His previous encounters with the Klan suggest a man of fitness and vitality. Even the bullets that found him couldn’t fell him. Richardson was active, working at his carpentry, running a grocery, traveling to Atlanta to legislate and returning home to be a leader in Athens. Is this a man who gets taken by pneumonia in the prime of life?

So, was it a cover-up? After a year of increasingly disingenuous and deceitful coverage protecting the Klan, did the Southern Banner and Watchman (the papers would soon fuse into one) contribute to the Klan’s cause once again? After reading Athens papers during the course of 1871, when full-throated celebration of the Klan turned tactically taciturn in collective protection of the Klan, a quiet, misleading mention seems exactly how the Klan-friendly papers might have assisted the armed wing of the movement. Conversely, a bit of gleeful and overt grave-dancing might have just as likely followed the natural death of someone like Alf Richardson. Black death, especially when it came to black men, was not addressed with any sort of reverence or respect in the pages of Athens papers. Even white Republican death was something to cheer in Athens. (An 1866 stereopticon exhibit shown in Athens made the mistake of projecting Abraham Lincoln, just recently assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, onto the screen, sending the crowd into foot-stomping and bellowing chants of “Booth! Booth!”) It’s rather curious: after all the ink dedicated to Richardson and Republican malevolence since 1868, news of his demise is meager and emotionless. Who died? Alf who? Which was he? Oh, we had a black legislator named Alf Richardson? You don’t say.

What If the Truth Had Been Told?

The Watchman publisher, John Christy, had followed Richardson to Washington that previous summer and, having sworn an oath to tell the truth, reported to Congress that the Klan did not exist in the state of Georgia. His mission was to erase and negate Richardson’s testimony. Christy, a committed white supremacist, knew that newpapers like his could control what is known. Richardson knew this too. “What I am telling you is what people come right to me and tell me,” Alf told the House Klan committee about the endless tide of bloody news that traveled to black legislators in Atlanta from around the state. “Thousands of things are done down there that are never reported in the papers, and nobody ever knows anything about them.” White violence and terror were ambient in the South, and eventually the fear became law. But very little of the volume of violence was broadly known. One is left to wonder how American history might have been different were the whole truth told at the time. From every whipping and beating to torture and murder, what if newspapers like Christy’s Watchman and the Southern Banner had filled their pages with the full catalog of carnage authored by white terrorists? Could a white conscience have been appealed to if everything had been reported, or reported accurately? If citizens and politicians, North and South, had understood the horrific ubiquity of the violence, could white America have steered away from its evil?

We’ll never know if the white American conscience could have been reached, because the full story was never told. And we’ll never truly know what happened to Alfred Richardson, father of Laura, Ella and Amanda, husband of Fannie, leader of men and killer of Klan. Power in America has always been about who controls the story, who presides over the truth. When the Klan was threatened, they were strategically struck from the story by men like Christy. When white power reemerged after Reconstruction to forge an apartheid, totalitarian state across the former Confederacy, the song of a gallant, salvatory Klan was sung by Hull and Morris. Indeed, as white supremacy continued to reign so too did a national mythos necessary for its survival. And thus, later, as white supremacy was increasingly countered with an opposing, if unequal, force throughout the mid-20th Century and into the present, truth itself became a contested terrain. The battle over Alf Richardson portended the total war for the power of truth. For us to consider Alf Richardson together here in an Athens paper is to meet on a battlefield of that war, to borrow a phrase.

Now that lack of a shared truth divides us nearly as much as on the eve of the Civil War. We see it in today’s postmodern political media environment: What incontrovertible, self-evident fact believed by a contemporary liberal would change the mind of a Trump-era conservative? Conversely, what conservative truth buttressing Trump’s power would change the mind of a liberal? There no longer exists the sort of shared reality that binds a single people. We have become epistemologically balkanized, separated by a border scarcely less effective than the Mason-Dixon. It is almost impossible to imagine reconciliation. A new technological terrain allows for the tactics of pioneers like John Christy and the Klan’s chroniclers to operate at the national scale, with an ever-widening gulf between our separate truths. But is this a bad thing? Was not a single, dominant truth the first tool of the oppressors? Alf Richardson was born into the mass of the voiceless, those without a speaking part in the American historical drama. He fought so that the powerless could speak their truth, and both in life and death the powerful moved to silence him. That he still speaks now is a victory.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.