Since Vic Chesnutt’s passing, Flagpole has received several inquiries from his fans hoping to revisit our 1999 interview with Chesnutt. Our web archive doesn’t go quite that far back, but we were able to unearth the interview and have reproduced it below in its entirety. Here is the two-part article by Travis Nichols titled “It Weren’t Supernatural” which originally ran in October of 1999.

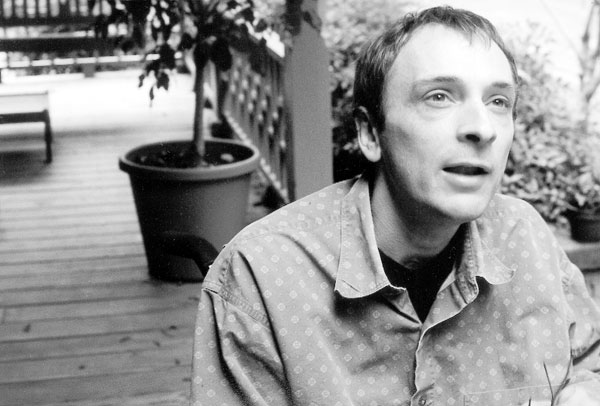

For over 10 years, Vic Chesnutt has been blending country music’s heartbreak with Wallace Stevens’ poetic panache to form a truly original brand of folk pop that has earned him titles ranging from “The New Dylan” to “The Folk Faulkner.” From his first album Little released on Texas Hotel Records in 1988 to the most recent Capricorn release The Salesman and Bernadette, Chesnutt has accumulated a catalogue of bizarre poetry that fans fiercely hold dear and other artists fawn over. Sitting out on the porch of his house on a rainy Monday afternoon, Flagpole writer Travis Nichols spoke with Chesnutt about his first ukulele, the creative process and “The Night The Lights Went Out in Georgia.”

Vic Chesnutt: Are you okay, are you cold out here?

Flagpole: No, I’m fine. I’m actually kind of hot from walking here.

Vic Chesnutt

VC: Because if you got all soaking wet, we can go upstairs. It’s warmer upstairs.

FP: Thanks, I’m really fine.

VC: Okay.

FP: I guess I’ll just go ahead and get to the meat.

VC: Yeah, do that.

FP: Well, for you how does a song differ from straight conversation or something like a short story as a form of communication?

VC: Well… it’s um, it’s funny about that. It’s different from conversation, because for me I’m alone when I do it. I’m by myself most of the time when I write songs. When I do work with other people we’re not talking. We’re not chronicling conversation and writing that down; we’re talking about ideas or stories or something like that, so it’s not like a normal conversation. It’s also funny because I know a lot of people who write songs, and when you hear them talk they’re brilliant, but then their songs suck, and you think why? They’re such brilliant conversationalists why can’t they write decent songs? I don’t know the answer why they sometimes can’t do that. They ask me for advice sometimes, and I say, “Goddamn, just tape yourself at a party and sing that, cause that’s brilliant.” But then when they get down to writing songs they get in this tense way, and they think, “Oh, I’ve got to say something brilliant.” There’s a lot of pressure on songwriters sometimes to make each song they write have power or be the greatest song ever written or something. And that was the way I was when I first started writing songs a long time ago. When I was a kid, you know, I wanted to do that. I wanted every song to be brilliant. I’d write love songs, ’cause that’s all I knew, and it was a heavy responsibility. Now I just try and spew it out.

It doesn’t come from where conversation comes from, I don’t think. It has a lot more hocus pocus. It’s like alchemy in a lot of ways. You know, in a laboratory, pouring this and that and seeing what color it turns and going from there. There’s a lot of research involved in my case. Research and development.

FP: How do you mean?

VC: Reading and studying my environment, things like that. It’s always an investigative process to start to get the songs to shake down in my case. When my songs shake down, it’s when I’ve made the discovery. I’ve been investigating for a week or two, trying to find out exactly what it is that makes whatever I’m trying to get at pop. What it is when I see the old lady, when I see her walking by, what she tells me. What pops about it, you know? So that’s why it’s like research and development.

FP: So it’s got that scientific aspect and also this magic?

VC: Yeah, there’s a lot of hocus pocus. You know, magicians don’t just throw it out there. There’s a lot of human nature involved – science, optics and anthropological research, you know. Studying what makes people do what they do. And I do that. I study that. I’m not saying that for every little song that I do I spend weeks on end researching. I do a lot of – like I said before – spewing, but it all comes from somewhere. It’s like I’ve got this little pouch, and I’m stuffing things in it and then it swells and sometimes it spews and pops and things come out. A lot of times I’ve got to go searching through it, picking through it and adding to it for long periods of time ’till there’s enough there to hold up.

FP: After you’ve been working a while and you finally get the moment right, do you just leave it, or do you do a lot of revision afterwards?

VC: I always revise. Because the way I write songs is very condensed. I don’t use very many words most of the time. I don’t write, like, “Tangled Up In Blue” all the time where it’s reams and reams of crap. I mean, I love that song, but my stuff is all boiled down. Every little word is very important. There’s a lot of times when I’m writing a song and it’s going really good. I got a whole verse. It’s pretty easy. And then it’s down to this one syllable. I’m sitting there for hours saying, “I can’t figure out the exact right word. There’s only one word that will fit here, but what is that word?”

FP: What do you usually do then? Do you just sit and stew on it?

VC: I sit there, and I stew on it, and then a lot of times what’ll happen is then it’ll just come to me – that word. Later in the day or later in the year, at a later date, and I’ll just go, “Oh yeah, that’s the word.” I’m not very good about, you know, thesaurus looking or anything like that. I am a dictionary-aholic, though.

FP: Really? What dictionary do you use?

VC: Well, I’ve been using the same dictionary for a long time now. It was one my granny had. A Random House dictionary, a big fat paperback. She always used it when she did crossword puzzles, and then when she died, I got that dictionary, and I’ve used it ever since. A lot of times when I’m writing songs I won’t know what the word is. I’ll be like, “Where did that word come from? What is that?” and I’ll know what it means, but I’m like, “How did I know what that means?” and I’ll look it up and I’ll be like, “Well, how do you spell it?” I’m very verbal. Always, for some reason I’ve been fascinated by language. Though I don’t have a huge vocabulary at my beck and call, but I have a strange memory for words.

FP: That fascination comes out in your songs – in the words that you use and also the names you’ll list in songs.

VC: Yeah, I’m into historical personalities as a touchstone to reality.

FP: Like in the song “Wrong Piano” you list people like Bob Guccionne and Rupert Murdoch in the context of mistakes, and it works really well. Is there always a method behind a list like that, or sometimes do you just like the way the name sounds so you just throw it in there?

VC: Well, most of the time they’re there for a certain reason, you know, like I said, like a touchstone or a springboard from reality into the sort of dreamland or whatever.

FP: When you use symbols or more abstract images are you ever afraid you’ll lose the listener?

VC: I’m super into symbols. I use them in just about every song, and I guess I don’t expect the listeners to really follow all the way. The songs are coded, and there’s no way for the listener to break the code sometimes except just to let it sink in, and then later it will bubble up kind of like an artesian well. That’s more how I expect the listener to take it. [A squirrel above Vic’s truck drops an acorn onto the hood.] I hate squirrels.

FP: Yeah, they’re evil little rodents. I’ve got an uncle who just sits out on his porch lobbing clods of dirt at them and the rabbits that try and get into his garden.

VC: I hate squirrels. I like rabbits, but luckily I don’t have to fight them here in town. But if they were getting into my garden, I’d be sitting out there all night shootin’ em. I killed ’em a lot when I was kid. We had a garden, you know. I’d catch ’em every night in my rabbit box, and then I’d kill ’em in the morning and freeze ’em before school.

FP: Did you do anything with them?

VC: We ate ’em. It’s good. Wild rabbits are kind of strong tasting. It’s dark meat.

FP: Were they like jack rabbits with the big haunches and everything?

VC: No. They were little bunnies.

FP: You ate little bunnies as a kid?

VC: Yeah, little bunnies. Wild bunnies.

FP: Being the verbal person that you have been since you were a kid, when did you decide that being a songwriter was the best outlet for your verbal interests?

VC: Well, I started writing songs as a youngster, but I didn’t really have anything to say. It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I realized songs were a special place to say things. Before, it was just like candy – ear candy. Until I got to be a teenager. When I was a kid I wrote songs like love songs and stuff.

FP: I read that the first song you wrote was a song about God. That sounds like you had something to say.

VC: Yeah, that’s true. It was called “God.” That’s the first song I can remember writing.

FP: How old were you?

VC: I don’t know, probably third grade or second grade. I didn’t play any instruments then, I just wrote the words down and sang ’em to a melody. Later, I started playing trumpet, and then I would write words and write out the notes on paper. Then I got a ukulele and started playing, and then I got a guitar. When I was 14, I got the ukulele, and when I was 15, I got a guitar.

FP: Why a ukulele?

VC: ‘Cause it was cheap in the Sears catalogue, and I ordered, it and they delivered it to me, and it came with a book with a bunch of songs and how to play chords.

FP: No big interest in Russian folk songs or anything like that?

VC: Mmm, no. [Laughs] Tasty. Tasty.

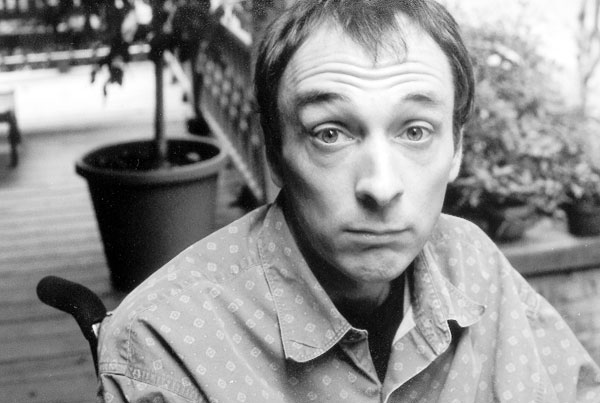

Vic Chesnutt

FP: Just asking. Your grandfather wrote songs, and your grandmother wrote lyrics, right? How did that effect how you looked at songwriting?

VC: Well I think it punctured the bubble of mystery around it for me. I knew it was something you do. My granddaddy wrote songs for my grandmother on their anniversary, so I knew it was something you could just sit around and do. It wasn’t a freaky thing, and there wasn’t any great mystery attached to it. I knew you could have fun and write songs, so I did that all the time. Writing songs about stupid things like my dogs and fishing trips, my mom and dad – if I was pissed off at ’em. It was easy. I’d just write a little song called, “You Suck.” [Laughs] I’m really thankful for that sense that songs were easy, I think. I liked what songs did. They could make you all sad, you know. A song about a dog dying would make me all sad. I always liked the music even before I knew they were saying something.

FP: Did you ever think you would become a poet or a writer instead of a musician?

VC: I never thought about writing anything else really, and I… [A big van drives by.] Goddamn. She had some big hair.

FP: I didn’t see her.

VC: She got a WNGC sticker, too. [Laughs.] Yeah but I never thought about writing anything else, really. Especially after I started writing my songs – around 16, I think – when they started to turn into what I write now. When I started writing songs with the same basic kind of premise that my songs have now.

FP: Which is what?

VC: Well, I don’t know. They weren’t love songs like other people write or political songs like Phil Ochs. They did have something in common with Phil Ochs, perhaps. But, I was super into Leonard Cohen when I was 16. Big time. I wrote poems too, but mostly everything was for songs. I didn’t read any poetry at that time.

When I was in my 20s, I thought maybe I’d try and write some other stuff. I wrote poetry a lot when I was 18 and 19, and that’s how I thought I was going to go for a long time. I was studying English in school, and I thought, “Well, I’ll write poetry,” because I did it all the time, and it was very interesting. I still wrote songs, but they were two separate things. For one I was thinking about singing, and for the other I wasn’t thinking about singing. They came out two different ways. I still write both. And you know I’ll write a little short story now and then. I don’t spend a lot of time doing it but every now and then I do write ’em. Mostly during the times when I’m writing songs.

FP: Do they just sit up there on your computer or do you give them to friends?

VC: No, they just stay there. I don’t let anybody see ’em. Not even Tina. Maybe someday I will, but not now.

FP: Do you still see it that way, where you’ve got the poet voice and the songwriter voice as two separate things?

VC: Well, now they are a lot closer together, I think. I don’t know. They share a lot in common. In fact sometimes I’ll put my poems to music.

FP: Do you feel like you have a lot more room to be playful in a song than you do in a poem?

VC: Well, yeah somewhat.

FP: Just because it’s naturally more of a performance?

Vic Chesnutt

VC: Exactly. Right. Yes. A lot of times when I’m writing poetry it’s even more – which is probably hard to believe – it’s even more self indulgent than my songs. More cryptic and more encoded.

FP: That would be maybe what the good conversationalists who can’t write songs are thinking. They’re more on the spot. They think that a song – like a poem maybe – is a sacred form that can’t be played with.

VC: That’s what people do. That’s the way they feel about songs. You know, they think that it’s a sacred form. But I don’t think that way. I don’t do that. I’ve written so many songs over the years that anything goes, pretty much. I’ve written every kind of song. Also, I’ve written a lot of good songs over the years, you know, and that kind of frees me up sometimes, ’cause now I’m like, “fuck it,” you know, “fuck it.” I’ve written these heavy. suicidal songs, and now I wanna write something different.

Also, I’ve got this backlog of a lot of songs that haven’t been recorded, and that frees me up when I’m actually goofing around and writing songs. Sometimes that’s bad, though. Like the last couple of songs that I’ve written are just as stupid as they come.

FP: What do you mean?

VC: I mean stupid. It’s like I’m saying, “Let me rub your rascal.” That kind of thing, you know. Just stupid.

FP: I don’t know. That could be worked into something pretty nicely.

VC: Well, it’s just goofing around.

FP: Since you’ve got that padding, though, the pressure’s off to some degree?

VC: Right. But then internal pressures start getting into you. You spend a couple of months writing shitty, and then you’re like, “Goddamn it, I can’t write songs anymore! I’m so depressed! My brain’s gone! I’m burnt out!”

FP: So do you sit down and write most every day?

VC: Yeah, I do.

FP: Do you have a set time, like in the morning or something?

VC: Yeah, I do a lot in the morning. I do a lot during the day, when I should be taking care of business.

FP: So it’s still kind of a distraction for you?

VC: Yeah. It’s like a Valium for me. It’s good for me to do that when I get all crazy. It’s good. I can just write and float off into my own little world.

FP: You’ve said that you write best when you’re distracted, or when writing the song isn’t the only thing you have to get done. Is that part of the reason you collaborate? So you’ll have somebody to distract you and then say, “No, it’s done. Stop fucking with it.”

VC: Well, the thing I like about collaboration is that it’s constantly putting up walls. When you’re working with someone else you’re building off of what they build. When I’m by myself writing it’s all building off of what I do. With collaboration, it’s fun improvising and tacking on to what somebody else has done. There are new possibilities. That’s what I like about collaborating.

FP: Do you usually swap tapes beforehand? Do you give somebody like Lambchop or Widespread your songs before you get together, or do you usually just get together and see what happens?

VC: Well, with Lambchop I wrote all those songs, and with Panic I wrote all those songs, too. I’d just give ’em to those guys, and they’d play em. I’ve written with some other people like Kelly Keneipp, and he’d have some chords written out, and I’d just make up a melody and write the words, which is great fun for me. It’s very exciting. And when I wrote with Jeff we did kind of the same thing. Me and Jeff was a little different, though. He had a melody in chords and no words, so I just put in words to his melody.

FP: Are you talking about Jeff Mangum?

VC: Yeah.

FP: When did you guys get together?

VC: Just recently.

FP: Really? Has it gone pretty well so far?

VC: Yeah, it’s going great. Another thing I did with Jeff that was pretty cool was he came over and played this song he wrote, and he was asking if I could maybe help him put a part on there or something, but when he played it I was like, “Fuck, that sounds like a whole song to me.” I told him to leave it. He talked about what he was thinking about when he wrote it, and I wasn’t thinking about collaborating on that aspect – we were working on this other song, too – but then like a couple days later something shook down that kind of had to do with what he was singing about, so that was kind of cool.

FP: So you wrote an answer song to Jeff’s song?

VC: Yeah a little answer song. Exactly. That was pretty neat. I don’t do that very often. We haven’t recorded anything yet, though. So far he just sings a song, and I tape it, and then I try to put some words to it. Also, I gave him some songs, some lyrics for him to put music to. It’s been great working with him. We’re going to try and do a little story.

FP: Like a song cycle?

VC: Yeah, I think we’re going to start working on a song cycle story. I think we’re headed in a certain direction with the story, and it’ll be interesting to see where it goes. Basically it’s just characters, you know; it’s all characters.

FP: Are you guys interested in the same sort of music?

VC: Umm, well we haven’t really talked about what we listen to or anything. We haven’t talked about that at all, actually. You know, hardly ever is it like me and whoever I’m working with are like, “Hey let’s write a song like him,” or whatever.

FP: When you were a teenager and you were writing songs, was there ever a songwriter or somebody like that whom you emulated?

VC: Well, Sound-wise I liked Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan and The Velvet Underground. And I liked certain Beatles songs. I really liked some of their lyrics a lot. Lyrics to songs like “Hey Bulldog” and “Cry Baby Cry” were huge influences on me. “In the Court of the Crimson King,” too, for some reason. Lyrically, that was really high on my list. I’d listen to Bob Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding” a lot. I was really into that lyrically. Leonard Cohen, I mean, almost anything he did I liked even though some of it was goofy as hell. You know, half of his songs I have to laugh at cause he’s so horny and it just cracks me up. But even in those songs, there’s always a line where you go, “God! That’s great!” A lot of times I’ll feel like that guy in that movie Amadeus – that other guy, the other composer. Sometimes I feel like him, you know, with Leonard Cohen. I’m like, “What a fucking little freak asshole he is. What a goofy bastard Canadian freak,” but then, you know, he wrote some great songs. Same with Dylan, you know. How did he do that? He’s such a dick and an idiot. He’s basically an idiot, you know. But those were the songs I was really taken by. That’s where my imagination was drawn to. That’s when I started finding my own voice, when I started hearing these songs.

I grew up on country music, and for some reason, I just could never get it going on. I could never write like “The Night The Lights Went Out in Georgia,” or something. I just always was twisting it so it went somewhere weird. I always wanted to write “The Night The Lights Went Out in Georgia” – that kind of song. I think I’d be happier if I could write just that over and over and over and over.

FP: Do you think so?

VC: Yeah, I’d be happy if I could do that. Just an endless stream of “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia.” But for some reason I get my jollies out of going in a different way.

FP: Even though you said songs didn’t have a whole lot of mystery to them when you were a kid because your grandfather played, did you still have heroes as a kid who were songwriters?

VC: When I was a little kid I really liked Herb Alpert, because I played trumpet. I really liked trumpet players like Louis Armstrong and Herb Alpert and even Doc Severenson, ’cause, man, he could hit the high notes. So I was super into those guys, and like I said I was super into these story songs. The ones that really got me were the ones that had stuff goin’ on like dogs dying. I didn’t like the ones that were just mushy, you know, cause, “eww that’s mushy.” I liked the ones where people were dying. “Billy Don’t Be a Hero,” “The Night Chicago Died,” – story songs like that.

FP: It seems that country songs have always had more of a capacity for that kind of tragedy-and-comedy combination that other genres just don’t have, and in your songs there’s the same sort of mixing of wit and sadness. What function do you feel this humor has in your songs?

VC: The humor is important in my songs and in my songwriting because I have a tendency… I like to push a song towards the morose and then jerk it back. I think it has a lot to do with my schizophrenic nature – just my personality, where even in the darkest of days there’s goofy. I see the goofy in everything. I can’t help it. I have this split thing. I always see a couple of sides. It’s a curse. It makes me wishy-washy. So I always feel like even in the dark songs, when I’m feeling dark I’m not going to say no to the goofy if it presents itself. I’m even going to go search for it.

FP: It takes a definite narrative talent to pull something like that off where the song doesn’t sound just completely ridiculous…

VC: Well, ridiculous is a thing that I don’t say no to either. I think this is one of the things that makes my songwriting important to some people. I’m not afraid to be goofy in a way. I’m not afraid to be ridiculous in a way. I say things that are preposterous sometimes. I make people say, “What the?! Why?! Why would he do that?” I’m kind of fearless that way.

Vic Chesnutt

FP: There’s a sense of humor that you have on-stage and in your songs that’s so self deprecating it seems that it must sometimes go from being a healthy sort of self skepticism to the flat-out ugly, “I can’t get out of bed, and I can’t show anybody my songs, because they’re just dumb” kind of self deprecation.

VC: Yeah, I do that all the time. That happens all the time. I never would have pushed my songs on people. I hate that now, thinking that I would push it. I had my songs, but I never thought, “Oh yeah, these are songs people gotta hear.” I never thought that way. I wrote ’em and thought “cool.” I played ’em for my friends, and I played ’em sitting around the house, and then I played ’em at a party, and then somebody said, “Hey, you gotta play these,” and I was like, “Ugghhh, I’m scared,” and they were like, “We got you a gig,” and then people had to physically take me down there, because I didn’t want to go. Then people were clapping, and they were like, “Those are great! Those are great!” and I was like, “Really?” Then it was like somebody said, “Do you wanna open for our band?” and I was like, “Uggghhh, I don’t know… okay.” I was so nervous about it, but this approval I got from everybody was infectious. I’d written all these songs beforehand, and I would have kept doing it. It was my own private thing. I thought I was going to be an English teacher or whatever, and I could have written songs forever and written poems. I didn’t have to show them to anybody, because it was just a byproduct of my nature in a way. You know what I mean? Something I would just do. Some people twist their hair, you know. I write songs.

FP: Do you ever feel regrets about it now that it’s this big public thing? Has it changed it?

VC: It has changed it. A lot. I regretted that so much a couple of years ago: I thought I ruined that because before it was just about songwriting and now I’m going out and playing. Earlier in my career, I started going out and opening for bigger acts, and I thought I had to change my songwriting to make it a little more catchy or whatever. I was opening for Bob Mould in 1990, and there I was singing “West of Rome” in front of a thousand people, and they’re all just looking at me like, “You fucking freak.” Some people dug it, I guess. I got into this thing where I’d write shorter pop songs so, yeah, the melodies were changing and stuff like that. Before, I had wanted my songs to be linear and not cyclical. I wanted them to do this kind of graph and then they started being these little figure eights or whatever and I thought, “Goddamn it. I’ve ruined what made me interesting to myself. It’s ruined now, and I can’t get it back.” But you know, I was like, “What am I going to do?”

FP: Do you feel like you got it back?

VC: Well, I mean, I just had to start… Yeah , I have. I had to remember what I liked to do earlier, and I tried to do that. This is like 1994, 1995. Right after Is the Actor Happy? where all the songs had these weird choruses and shit, and I was like, “What am I doing?”

FP: So you weren’t happy with that record?

VC: Oh I loved it. It was all those songs that I had been writing just for that – for opening for bigger bands that I thought somebody in the audience who didn’t know me could latch onto a little better. For my next record I was trying to fight that a little bit. I had several little chorusy songs, but again with the schizophrenia, “I can’t do this… but I gotta. I gotta have the chorus, but this one, I don’t know… ” At that time I couldn’t remember who I was as a songwriter or as a music maker. That whole year there when I was recording that record I was running around like a chicken with my head cut off trying to recall what I did that I liked about songwriting.

FP: How do you feel now? Do you feel like that period helped your progression as a songwriter?

VC: Yeah. I got through that little crisis, and I remembered what it was that I liked about my earlier songs, and now I feel more comfortable now with the way I am now and the way my head is. Songwriting-wise, not life-wise. Songwriting-wise I’m doing what I do, and I’ve been trying not to think too much about an audience. I’m trying to forget that audience is out there. Trying to work through my little alchemy projects.

FP: I’m glad you brought that up again. In terms of alchemy, you’ve said you like artificial inspiration. Which drugs are best for inspiration?

VC: Well, I drank ungodly amounts of liquor in my 20s, and one thing I found about alcohol that was good for my songwriting was that it eliminated pressure. I wasn’t nervous if I was drunk, I’d just be scribblin’ away. If I was drunk and writing songs I could concentrate on whatever I was doing and not think about how fucked up the world is and other things. So that was good. I thought that was a good drug for songwriting, and, you know, acid.

As a teenager and all through my 20s I took ungodly amounts of acid. I would never have written the songs that I had written if it wasn’t for this kind of kicking open the doors of perception kind of shit. I learned a lot about thought processes and how humans think and perceive from that. Every time I took some acid I re-learned what it was like to be human again which was good. It turned me into a baby every time. It was a humbling experience and a good shrinker. Anytime you start feeling self important and then you take some acid, that’s evaporated immediately. You are a nothing piece of crap. At least I was.

FP: It’s terrifying.

VC: It’s horrifying, and I found a lot of inspiration in that horror, the overwhelming vastness of the universe.

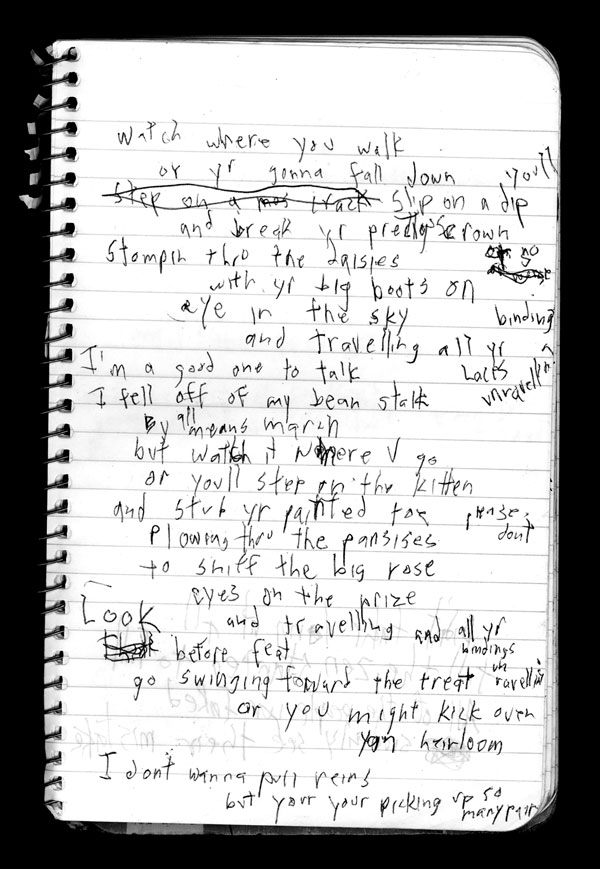

Some of Vic’s handwritten lyrics.

FP: Acid does have that moment where you realize you can’t look forward to being dead anymore because you see what happens after you’re dead and it just goes on and on. There’s nothing you can do after that but think life is kind of goofy.

VC: Yes. Yes. Yes. I can see it all over everything I write, the influence of LSD. My world view is completely, I don’t know, I wanna choose the right word. I would say it has been sharpened. My vision has been sharpened. My world view has been shaped, I guess. I mean, the drug isn’t for everybody, I mean it’s not. Liquor isn’t either. I mean I ruined my liver completely. I wish I could drink right now, but I can’t.

FP: Doctor’s orders?

VC: Well, long past the doctor now. It wasn’t that.

FP: The whole idea of acid amplifying what you’ve already got is put out pretty clearly in this book Acid Dreams. It talks about everybody in the ’60s taking acid – all these left leaning boho kids taking acid and thinking that the whole world would feel the same way they did if the whole world took acid, but people in the CIA were taking acid 10 years before all that, and they were using it as a truth serum. It was a totally different thing for the CIA.

VC: Right. Well it’ll scare you to death. I don’t see how you could get any truth out of anybody.

FP: Just get ’em crying on the floor, I guess.

VC: Oh god. No doubt, no doubt. I spent lots of hours just bawling my eyes out. I read a book on that, too, a while ago. It was really scholarly. It completely ragged on everybody in the ’60s and said that these guys just completely fucking ruined it. They were idiots. Timothy Leary was the biggest fucking idiot in the world. “Let’s dose everybody in the whole world!” What a fucking idiot. He’s a fucking idiot. I hate that bastard.

FP: That’s one thing, you know, people who first start to take acid get really into Tim Leary, but I would think the worst thing in the world to have by you on acid would be that Tibetan Book of the Dead. It would just put all this pressure on you to have a big, transcendent experience, but then if you don’t, you’d start feeling like you were defective.

VC: That’s one thing – being defective. I mean, I knew it before – that we were defective – but acid reinforced it. That was a huge influence on me. I haven’t taken it in a while, well… I took it four months ago, a bunch of it, but it wasn’t like it was before. I took it every day for a year in like 1985.

FP: Wow.

VC: I had vials of liquid acid in my freezer, but it wasn’t like a party. I was doing serious research into the depths of my horror – my self.

FP: Do you feel like you have any after-effects now?

VC: I don’t have flashbacks or anything or feel like I’m burned out. I don’t have residual shakes or blurry trails or anything. No physical things. I’m humbled from it, that’s about all. I feel like crap. All the time.

VC: But in an enlightened way, right?

FP: Well, I know it. I’m not trying to bullshit anybody. I’m nasty, I’ll admit it. Humans are nasty beings. That’s all I know. Everything we do. We’re corrupt. That’s one thing I’ve learned – babies are corrupt; everybody’s corrupt. It’s not like an original sin sort of way, it’s just nature. I guess it’s not defective, though I think modern humans are defective, it’s just cruel. It’s a cruel world so we have to be cruel to be kind. I mean, that’s not the only thing I learned – I learned little things – but it’s not for everybody, that’s for sure. I mean, I’ve been a depressed being my whole life, and acid helped me realize why, but some people wouldn’t be able to handle it. It’s going to scare them to death, and they’re not going to be the same. If you’re just barely holding it together, then you don’t need to be taking acid, because you’re going to crack. You’re definitely going to crack. I mean you look at Daniel Johnston. He’s a fucked-up person, and the Butthole Surfers gave him all that acid, and he just lost it.

FP: He’s coming here pretty soon.

VC: Yeah, I’ve gotta go see him. They ain’t pretty, but I love his songs. Like in 1990 and 1991, I listened to him all the time. It was good for me, because he was fearless, too. He was naive like a kid, totally willing to embarrass himself to no end. After that, I was like, “Damn, I’ve got to open up now. I have to open up like him.”

FP: Who else do you listen to now?

VC: Well, hold on, I got to finish talking about substances.

FP: Oh. Right. Go on. Go ahead.

VC: Well another one – there’s a couple more – now the weed is my favorite songwriting substance. I like it a lot. It’s not for everybody, either. It makes you paranoid. It’s good for me, though, because when I get shtoh-ned [Vicspeak for stoned] then I forget the world is around me. I can concentrate on whatever I’m doing even though it’s a weird concentration and sometimes stupid things come out of it; it’s a good thing. I can spend hours trying to figure out that word I need. I love it. I love it. I wouldn’t want to be writing a whole novel or anything, but for song-length stuff it’s great. The thing about it that’s great is that it gives me a weird ability to see connections between things that I wouldn’t normally see if I weren’t shtoh-ned. You can see patterns, and I think that is really good for songwriting. It’s like you can see eight spots on the ceiling and when you’re not stoned you think, “Oh eight spots,” but when you’re stoned and you see eight spots you’re like “Whoa, look at it! It’s… it’s an airplane!” That kind of thing. And that’s good for songwriting, because I can notice patterns in words.

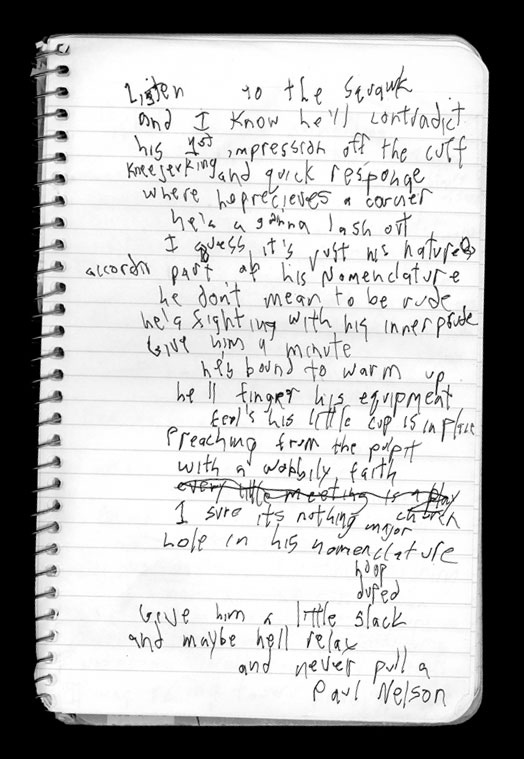

Some of Vic’s handwritten lyrics.

FP: You’ve said that with lists of things – like in the song you sang at the Flagpole Music Awards, the things by themselves aren’t that meaningful, but when you string them together they take on meaning.

VC: Right. Exactly. That’s a perfect example. That’s the thing that’s good about weed for me and songwriting. Another good thing about it is that it gives me energy to just go and go and not worry about if it’s stupid or not until later which is good for me because I get full of doubt all the time. It’s really good for that.

I wrote a lot of songs on X midway through the ’80s. I wrote certain songs on it- “Supernatural” was one and “Wrong Piano.” I don’t think it gave me any great ideas but I felt all inspired and it gave me energy to pursue. A song like “Wrong Piano” is two verses and I spent hours writing it and singing it over and over and over cause X made me crazy like that. Just 14 hours went by and I was like, “Hey look I got a two verse song!” Every song that I write you know I’m not all wasted writing it, but these are psychoactive compounds and they can’t help but do something to the songwriting process because it’s such a cerebral activity. I shot coke for a long time and that was like instant melodrama. The whole world turned to instant melodrama and I wrote a song like that and they were all kind of hyped in that way. Some of them were great, I have to admit, but they all had this sort of electric melodrama going on. Coke is like that you know. Hyped mock emotion.

FP: The themes of Drunk seem to have a lot to do with that sort of artificial inspiration – you know like, “Gluefoot.”

VC: Right. A lot of that record came out of trying to quit shooting up coke and I was drunk. That was like my two weeks in Charter; that was making Drunk. Like “Gluefoot” exactly. That’s spelling it all out in my own little code.

Heroin is the absolute worst drug for songwriting. For a whole year I didn’t write anything. I couldn’t string two words together, ’cause everything smelled like shit. I mean everything was rosy in a way, well not rosy but everything was just fine. That was the worst. I couldn’t write shit on heroin. Sometimes I thought it was good for singing, but I wasn’t cut out for that shit.

FP: I don’t know anybody who really is.

VC: Yeah. I just wish they’d legalize everything or legalize opium so people would be all dreamy and wouldn’t have to get to nasty old heroin. Antidepressants, I was on those for a long time, and I didn’t like those. They affected my body too much. My legs would shake. I didn’t think it blocked anything, but the whole time I was on ’em I couldn’t relax, cause I was shaking. Actually a lot of the songs on Salesman and Bernadette were written on antidepressants, but I was getting schto-ned, too. Everybody I know’s on antidepressants, so maybe I just need to try some different ones. I also injected a lot of speed – crystal meth and that sort of thing, ugly yellow compounds. I really liked that for songwriting. It’s not like coffee, you know. It does what they invented it for, keeping you going, and I’d be at it till it was over. I wrote a lot of stories and stuff then.

FP: That was Lester Bangs’ secret.

VC: Well, it was NOT a secret. That was definitely not a secret, but he did do that. A lot of writers did that. I think it’s a good thing for writers. But again, not that these things would make somebody a good songwriter, but I think they are good tools for songwriters if they’ve already got something going on. I mean it can’t not do something, ’cause they fuck with your mind, and you’re doing a mind thing when you write songs. It’s not like pilots or doctors – that’s a whole different interface – but songwriting is all internal. As a songwriter I don’t have to interface with anyone else. That’s the difference.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.