A crowd of a few dozen people gathered in the Madison County Senior Center earlier this month to observe one of our area’s saddest anniversaries—marking 60 years since Athens Ku Klux Klansmen murdered Lemuel Penn as he and two other Army Reserve officers drove across the Broad River bridge at the border of Madison and Elbert counties.

It was just nine days after President Lyndon Johnson had signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, and was the latest in a string of murders of African Americans and civil rights workers as the South resisted desegregation, said Dena Watkins Chandler, the Madison County woman who organized the event. After Chandler and others spoke to the crowd, the observance concluded about a dozen miles away at the bridge where Penn died, where many drove to drop flowers into the river below.

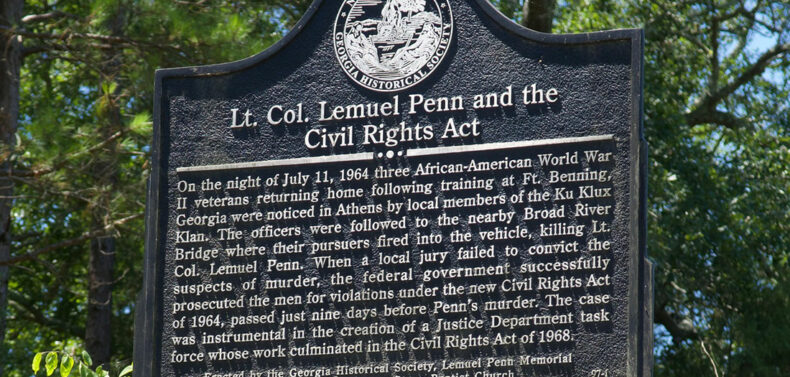

“I know we’re a lot better than that now,” said Chandler, who worked for years to get state approval to place the historical marker noting Penn’s murder that now stands near the bridge.

“The reason we keep bringing up Lemuel Penn [is] it wounds us in ways we don’t fully understand,” Chandler said. “I think it’s really important to talk about.”

The Klansmen—Cecil Myers, Howard Sims and James Lackey—were night riders, sanctioned by Athens police. The Klan was powerful in Clarke County at the time, with membership in the hundreds. The three had spotted the Black officers, all World War II veterans, in Athens, where they had stopped to change drivers at the UGA Arch in the early morning hours of July 11, 1964. They were headed home to Washington, D.C. from summer training at Fort Benning (now Fort Moore) near Columbus.

The night riders trailed the officers out of Athens for about 20 miles as Lt. Col. Penn drove up Georgia Highway 72 through Hull and Colbert, then turned onto Highway 172 toward Elberton on their way north.

As the officers’ Chevrolet Biscayne began to cross the Broad River Bridge, Lackey, driving the Klansmens’ Chevy II, sped to pull up beside the Biscayne. Sims and Myers fired shotguns into the officers’ car, killing Penn, 48, and wounding one of the others. Penn—a school administrator, father of three and Boy Scout leader who had earned a Bronze Star in World War II—was subsequently buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Klansmen were brought to trial on murder charges in Madison County, but an all-white jury, including some Klan members, acquitted them despite damning evidence, including Lackey’s confession.

Former U.S. Rep. Don Johnson, who witnessed the murder trial as a teenager—his father was the prosecuting attorney—had been scheduled to speak at the event but was unable to attend. It was a life-changing experience for Johnson, Chandler told the gathering.

Sims and Myers later did time in federal prison after being convicted of violating the officers’ civil rights—not under the new civil rights law, but a law passed shortly after the Civil War, said retired Western Circuit Superior Court Judge David Sweat, who also spoke to the crowd gathered in the senior center.

“The Klan was just out of control,” Sweat said. “The list of their acts of violence is pages.”

Although the Klan members escaped punishment for murder, the Klan’s power would soon wane in Athens and elsewhere.

As in Madison County, state courts elsewhere had been “largely ineffective” at holding whites accountable for their racially motivated crimes, Sweat said. Fear of the Klan even influenced federal courts. “At that time in the South, federal judges would go to great lengths to avoid the prosecution of Klansmen,” he said.

But the Athens Klansmen’s federal convictions marked a turning point. “That case may have had a tremendous influence on racial violence in the South because it established the authority of the federal government, United States attorneys, to prosecute cases using the Civil Rights Act of 1871,” Sweat said. The 1964 Act did not include the penalties that were authorized in the 19th century law, he explained.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.