If you think that many of the stores that Americans patronize are just selling products, think again. That coffee store with the green-and-white mermaid logo? It’s not just flogging joe, oh no. It’s selling a reflection of the consumer as he’d like to see himself—urbane, environmentally conscious, familiar with this thing they call “jazz.” That store with the apple on the outside of it? It promises us not only that we are people who need tablet computers, but that we are innovative and think differently from our peers.

When we see these highly recognizable logos, we intuitively know that we are purchasing not just “stuff” at that store. We’ll have what marketers call a “user experience” that will bolster our “consumer identity” and inspire “brand loyalty” by showing us something about ourselves that we like to see.

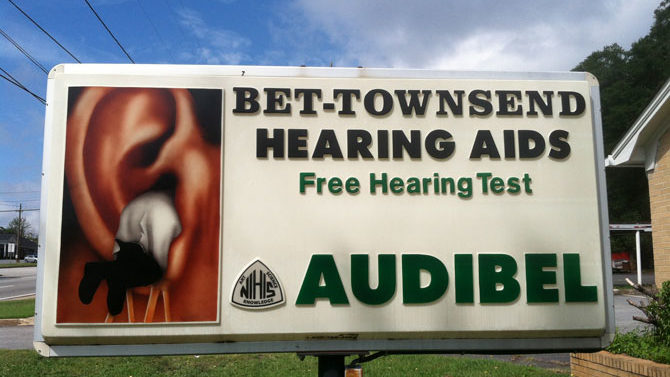

That is why, when I see a sign like the one outside of Bet-Townsend’s Hearing Aids on Broad and Rocksprings, I take notice. It’s so different from the sanitized, corporatized logos I’ve become accustomed to, and so incongruous with what should be a rather staid and stodgy business. The sign depicts a tiny man in a white coat who has climbed up a ladder and apparently become lodged in a giant, luridly painted ear. I’ve spent a lot of time sitting at the red light wondering about it while nervously pulling on my own ears. I try to imagine other health care professionals, like dentists, or gynecologists, advertising their services in a similar way. What kind of “experience” is this store offering its users? What kind of mirror is this strange sign holding up for its potential customers? “I am the type of exacting consumer who demands an exam so thorough that someone actually climbs in my ear”? Who had the idea for this sign? And what were they thinking? The sign was working on me in ways more professional logos don’t. Even though I do not need a hearing aid or exam, I had to pay a visit to this business.

It turns out that I’m not the only one who has wondered about this sign. The receptionist, Sue Wagoner, has worked there for all but two of the last 25 years and still has questions. “Oh, the sign!” she says. “Yes, the sign. They put it up when I was on hiatus, so I don’t really know. All I can tell you is that it looks like my old boss, the man who started this store.”

“How can you tell?” I ask her. “All you can see is his backside.”

She blushes. “Well, I mean, he was short.”

Bruce Townsend, the son of the original owner and the man who now runs the store, pokes his head out of his office. “This girl here wants to know about our sign,” says Sue.

“You want to know about our sign? Well, there’s quite a story behind that sign,” Bruce says, nodding. “See, my father, Jack Townsend, started this business in 1978. In 1999, we changed suppliers and had to get the old supplier’s name off the sign. So, we went down to Kinko’s and had a little homemade-type band-aid made up for it. It just said ‘hearing aids,’ and it sat there like that for six months.

Bruce Townsend and Sue Wagoner, the owner and receptionist at Bet-Townsend Hearing Aids. Credit Robin Whetstone

“Now, my father, he was a careful, conservative man. He was meticulous and frugal.”

“He was a deep thinker, and he had a good heart,” interjects Sue.

“He’d push you out of the way to get a nickel!” says Bruce, making pushing gestures. “He was a studious, pragmatic man. He never, ever bought anything without trying it out first. And so, one day this young man comes to the store. We don’t know where he came from, never saw him before. He’s an artist, you know, an African-American. In his heart, he’s a painter, but to eat, he makes signs.

“So, he comes in here with this book of signs he’s made, things he’s done up north. He talked to my dad for a long, long time, told him if he gave him a concept, he’d do a 3D, lifelike sign for him. And I don’t know what happened, I couldn’t believe it myself, but before we knew it, Dad was writing this fellow a check and climbing up on a ladder to pose for the picture of how he wanted the sign to look.”

“So, that IS your old boss!” I glance over at Sue, who looks vindicated.

“I knew it,” says Sue. “It looks just like him.”

Bruce continues: “I’d never seen him do anything like this, before or since. My dad, he was a fiscal conservative, a social conservative. He was conservative in every way, if you see what I’m saying. And this guy, well, he was an artist. He was, not to offend artists or anything, but he was…”

“Creative?” I suggest, “Unconventional?”

“Definitely unconventional,” agrees Sue.

“He was the kind of guy that normally my dad would have politely thrown out on his ear,” Bruce says. “But this time… That artist really struck a chord with dad. I think the two of them recognized something in each other. I guess it was just a case of two strange people, bonding.”

“Your dad was strange?” I ask.

“Well, like I said, he was extremely conservative. But, deep down, he was a real showman. He wanted to bring a little levity and humor to the community. He designed all the ads we used to run himself. He’d put funny little cartoons in them. And you know, the other day I’m running these fancy ads made with all the latest technology, and I’m standing here thinking, ‘When is the phone going to ring?’ And I dug out my dad’s old ads and just kind of changed a few things to reflect our new products, and all of the sudden people are coming in the door again.

“He had a gift for communicating with people, all people. The president of the university, the head of the Athens Banner-Herald, he fitted them with hearing aids. But then the guy who dug that ditch out there [he points out the window], he’d come in here and there was no difference at all to Dad. He was a true Southern gentleman.”

“There’s a picture of him in Bruce’s office, doing his mission work,” Sue offers.

We go into Bruce’s office where a poster-sized photo of a big man and a tiny girl with a hearing aid is displayed. “This was on a trip to Costa Rica,” Bruce says. “He used a lot of the profits we made to travel around the world, fitting kids with free hearing aids. When this little girl got hers and could finally hear, she followed my dad around everywhere.”

“So, your dad was also a good man,” I say, as we walked back to the main room.

“I told you, he had a great heart,” Sue says.

“At his memorial service in 2008, a woman we didn’t know told about how he came out to her house to fit her with a hearing aid since she was too sick to come in. It was around Thanksgiving, and he saw from her house that there was no money for any food. So, he went to the Kroger and bought her a whole Thanksgiving dinner.” Bruce throws up his arms. “And he never even said anything about it! We didn’t even know about it until he died.”

Bruce abruptly walks briskly behind the front counter, where he fiddles with some papers. We stand in thick silence for a moment, and I wonder what would happen if a customer came in right then to find the store’s staff and a disheveled girl with no need for a hearing aid sobbing together in the lobby. I also find myself hoping that I’d develop hearing problems as soon as possible, so I’d have an excuse to come talk to these people again.

“Anyway,” says Bruce, clearing his throat, “the sign came in, and we put it up. It’s been there since 1999, and people love it. We get comments about it all the time. People use it to give directions. ‘Oh, go down Broad ’til you see the sign with the guy in the ear…’ It’s kind of a landmark.”

“So, it does what it’s supposed to do,” I confirm.

“I think it’s helped grow our business from just providing hearing aids to making earpieces for musicians, and pilots, and motorcycle riders,” Bruce says. “Basically, anyone who needs an earpiece to hear or communicate comes here.”

As I pull out of the parking lot and turn down Alps Road, I try to imagine what I’d hear if I went into, say, Cinnabon, or TJ Maxx, and said “Tell me about your sign.” If I heard anything at all, it certainly wouldn’t be a story about a staff that’s been there for nearly three decades, or about a frugal yet charitable man who one day, for complicated reasons, abandoned his conservative principles and took a chance on a mysterious visiting artist.

If I have to have an “experience” when I venture out to buy something, this is the kind of experience I want to have. Not one that a marketing team thinks will suit me, but one that is predicated on my actual needs, be they for hearing aids, Thanksgiving dinners or quirky stories for the alternative paper. This is the picture I want painted for me, of myself as a real person who lives in a community with other real people. If it requires a hand-painted sign of a giant ear with a tiny man stuck in it to make it happen, well, so be it.

And so, I vote we turn over the making of signs and logos to the Jack Townsends of the world. The ones who don’t care about selling an experience, but who care about the product they offer, and the business they’ve made. The results might be weird, or funny, or possibly terrifying, but they’d also be a whole lot more like real life.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.