*Author’s Note: The term “mental retardation” has fallen into disfavor in the scientific community and is being replaced with “intellectual development disability” or simply “intellectual disability.” The American Association on Mental Retardation recently changed its name to the American Association on Intellectual and Development Disabilities. The term “mentally retarded” is also increasingly disreputable among professionals. To avoid confusion, and because the terms are familiar to most persons, the following article continues the use of “mental retardation” and “mentally retarded”. No disrespect is intended.

The idea that courts are not permitted to acknowledge that a mistake has been made which would bar an execution is quite incredible for a country that not only prides itself on having the quintessential system of justice but attempts to export it to the world as a model of fairness.–Judge Rosemary Barkett, dissenting opinion, In re Hill, 715 F.3d 284, 302 (11th Cir 2013).

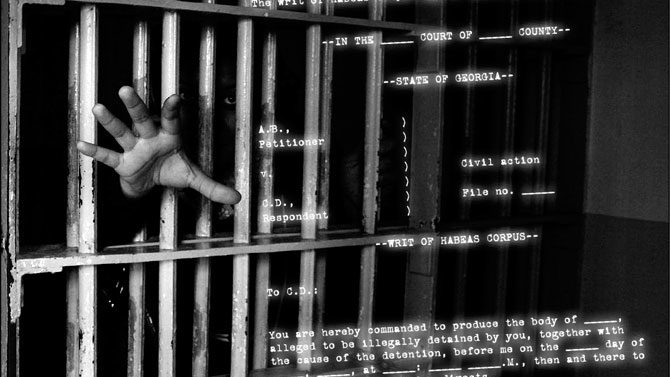

The significance of the writ [of habeas corpus] for the moral health of our kind of society has been amply attested by all the great commentators, historians and jurists, on our institutions.–Justice Felix Frankfurter, concurring opinion, Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443, 512 (1953).

[I]f ever temporary circumstances, or the doubtful plea of political necessity, shall lead men to look on its [i.e., the writ of habeas corpus’] denial with apathy, the most distinguishing characteristic of our constitution will be effaced.–Henry Hallam

The Great Writ of Habeas Corpus, the only writ mentioned by name in the U.S. Constitution, is the glory of our legal system. This writ provides a legal remedy in court for obtaining relief from unlawful imprisonment and is, as Justice Felix Frankfurter observed, “one of the decisively differentiating factors between our democracy and totalitarian governments.” Above all, the writ of habeas corpus is one of the most important bulwarks of the Bill of Rights. If an American is restrained of his or her liberty by the government in violation of the Bill of Rights and if other remedies have failed or are unavailable to correct the injustice, habeas corpus may be used to obtain release from that unconstitutional custody.

Tragically, habeas corpus has been besieged for the past several decades. The leaders of the attack have been the usual suspects: right-wing judges, right-wing legislators, right-wing commentators, and apologists for the law enforcement and national security establishments. This assault on the writ of habeas corpus has been shockingly successful. Step by step, both by statute and judicial decision, the reach of the writ has been restricted, the scope of the writ narrowed, and the effectiveness of the writ attenuated. At every step of this alarming process certain commentators have cheered.

Weakened Over the Years

Since the 1970s the U.S. Supreme Court, spurred on by conservative justices appointed by Republican presidents, has waged war on habeas corpus and in dozens of decisions has narrowed the reach of federal habeas corpus–for example, by inventing technical procedural rules to trip up petitioners seeking habeas relief (who typically are indigent, uneducated inmates without a lawyer) and to permit dismissal of their claims without ever reaching the merits. The most infamous is Coleman v. Thompson, a 1991 case where our highest court slammed shut the courthouse door on a state death row inmate (subsequently executed) by refusing to even consider his claims of violations of constitutional rights–all because his attorney had filed a piece of paper three days late in a state court!

Shortly after they took control of Congress, Republicans (who had pledged to do so in their Contract with America), pushed through the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), the first Act of Congress in our nation’s history designed to constrict and weaken the federal writ of habeas corpus and make it more difficult for prisoners convicted or sentenced in a state court in violation of their constitutional rights to obtain habeas relief. The AEDPA even engrafted a statute of limitations onto the writ–an unheard-of notion, so that now as a general rule illegal imprisonment cannot be corrected by federal habeas if the prisoner waits more than one year to seek relief.

The conservative U.S. Supreme Court loves the AEDPA. In 2010 and 2011, on successful appeals by prison wardens (who, along with prosecutors and police, are this Court’s darlings in criminal procedure cases), the Court reversed lower federal courts 10 times on grounds those courts had not adhered to the AEDPA’s requirements. The U.S. Supreme Court has announced that “one of the principal functions of [the] AEDPA was to ensure a greater degree of finality for convictions” and that the 1996 statute establishes “a highly deferential standard for evaluating state-court rulings.” This is coded language which means that denying the habeas petitions of persons convicted in a state court is the preferred course. Under the AEDPA, the federal habeas courts must, except perhaps in extraordinary situations where there has been a extreme malfunction of justice, rule against state convicts claiming violations of their rights. Under the AEDPA, the interest of the states in enforcing their criminal laws almost always trumps the interest of prisoners in vindicating their rights; preserving the power of state courts to administer criminal justice is the primary concern, and the protection of individual rights and the prevention of abuses of power are of secondary importance.

Since enactment of the AEDPA in 1996, Congress has enacted multiple additional statutes to hobble federal habeas corpus, including laws that curtail the availability of the writ in immigration cases, deny access to the writ to prisoners incarcerated at Guantanamo Bay, and even forbid federal habeas corpus relief for persons imprisoned in violation of the hallowed Geneva Conventions!

Here in Georgia since the 1980s the General Assembly has by statute been significantly curtailing the state’s writ of habeas corpus. In 1982 it borrowed many of the procedural technicalities created by the U.S. Supreme Court to limit federal habeas corpus and made them equally applicable to Georgia habeas proceedings. In 2004 the General Assembly enacted a law, patterned after the AEDPA, which imposes a statute of limitations on Georgia habeas corpus. In 1999 the General Assembly abolished appeal of right for habeas petitioners, a right that had existed for 150 years. The state retains its traditional right to appeal grants of habeas relief, but a habeas petitioner denied relief now may appeal to a higher court only in the discretion of the appellate court.

The writers, scholars, and others supportive of reining in habeas corpus defend their advocacy on crime control grounds. They disrespect the sanctity of habeas corpus. They even stoop to disparage the writ. In 1984 the Alabama attorney general published a law review article “debunking” the writ of habeas corpus!

Hostile, officious meddling with habeas corpus–belittling it, bemoaning it, downsizing it, fettering it with procedural and technical requirements, eliminating or reducing the grounds for granting relief–has only one purpose and can have only one consequence: decreasing the likelihood that imprisonment in violation of basic rights will be redressed via the writ and increasing the likelihood that habeas petitions will be denied rather than granted. As a result the Bill of Rights becomes less meaningful; illegal confinement becomes more frequent; the amount of suffering of those whose detained in contravention of their rights grows; and personal liberty, other individual rights and the rule of law sink precariously.

Warren Lee Hill, Jr.

The case of Warren Lee Hill, Jr., a Georgia death row inmate, is a textbook example of the sinister consequences of cutting back on habeas corpus. To be sure, Hill is not a model citizen. He appears to be a terrible person. He committed two murders years apart, received a life sentence for the first murder, and is now under sentence of death for the second one. This second murder was a truly horrible crime, and was described by a federal court as follows:

“In 1990, while Hill was serving a life sentence for the murder of his girlfriend, he murdered another person in prison. Using a nail-studded board, Hill bludgeoned a fellow inmate to death in his bed. As his victim slept, Hill removed a two-by-six board that served as a sink leg in the prison bathroom and forcefully beat the victim numerous times with the board about the head and chest as onlooking prisoners pleaded with him to stop.”

Nevertheless, the Bill of Rights was designed to place all Americans under its protective umbrella, whether they are good or bad, rich or poor, innocent or guilty. No one is excluded from the Bill of Rights, not even despicable murderers such as Warren Hill. “Not the least merit of our constitutional system is that its safeguards extend to all–the least deserving as well as the most virtuous,” Chief Justice Harlan Stone once wrote. “The business of the court is to try the case, and not the man; . . . a very bad man may have a very righteous case,” a Connecticut court observed the year the Bill of Rights was adopted.

Two other points should be kept in mind in contemplating endeavors to subvert habeas corpus. First, in the words of Justice Frankfurter, “It is a fair summary of history to say that the safeguards of liberty have frequently been forged in controversies involving not very nice people.” Second, in the words of Lord Macaulay, “the guilty are almost always the first to suffer those hardships which are afterward used as precedents against the innocent.”

What happens to Warren Hill is a matter of importance to all Americans. Depriving him of his basic rights threatens, in the long run, the rights of all of us. That he may be a contemptible murderer is irrelevant to the question of whether his rights under the Bill of Rights must be respected. Whatever his crimes, Hill has a right not to be unconstitutionally executed by the State of Georgia. Yet it appears that this right may soon be trampled upon.

In 2002, in its milestone decision in Atkins v. Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Eighth Amendment–the provision of the Bill of Rights that prohibits cruel and unusual punishments–forbids the execution of the mentally retarded. It is therefore unconstitutional for any state to put a retarded person to death. Warren Hill, whose IQ is around 70, is retarded. The experts are unanimous. It is therefore unconstitutional to put him to death. However, the State of Georgia is crusading for Hill’s execution. Because of the recent restrictions on habeas corpus, both the federal and the Georgia courts have refused his requests for habeas relief. It is extremely likely that the State of Georgia will soon execute the retarded Hill, even though it will be a patently unconstitutional execution.

The issue of whether Hill is mentally retarded was first litigated in his initial Georgia habeas corpus proceeding in 1996. Although the U.S. Supreme Court had not yet held that executions of retarded persons violate the Bill of Rights, the General Assembly had prohibited such executions by statute in 1988. That statute, however, prohibits the death penalty only if the person alleged to be retarded proves the retardation beyond a reasonable doubt. Georgia is unique in that it is the only death penalty state to require proof of mental retardation by a reasonable doubt. Twenty states require proof by a preponderance of the evidence; four require proof by clear and convincing evidence; and two states (and the federal government) do not set a standard of proof.

In December 2000 at a hearing in Hill’s habeas case in a Georgia superior court, seven mental health experts–psychiatrists and psychologists–testified on the retardation issue. The four experts put on the stand by Hill said that in their opinion he was retarded; the three experts for the state testified that he was not. The superior court eventually determined that Hill had proved his retardation by a preponderance of the evidence, but not beyond a reasonable doubt (although the court noted that the retardation issue “is an exceptionally close one under the reasonable doubt standard”). Since Hill had failed to satisfy the statutory requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, the Georgia courts denied him state habeas relief. Even though Hill had shown that it was more likely than not that he was retarded, the Georgia courts refused to disturb his death sentence.

When Hill then filed for a federal writ of habeas corpus, he was denied relief because of provisions of the AEDPA which reduced the number of claims that justify the granting of relief. Under pre-1996 federal habeas corpus law, Hill almost certainly would have obtained relief on his claim that it is unconstitutional to require a capital defendant to prove retardation beyond a reasonable doubt.

After Hill had been refused habeas relief by both the federal and the Georgia courts, something truly amazing happened. On July 27, 2012, one of the three experts for the state who in 2000 had testified that Hill was not retarded contacted Hill’s attorneys and told them that he had changed his mind and that he now believed Hill was mildly retarded. This expert, Dr. Thomas H. Sachy, a psychiatrist, after reviewing his original notes, his previous report, and additional materials from the court record, then signed an affidavit explaining in detail why he now “believe[s] that my [previous] judgment that Mr. Hill did not meet the criteria for mild mental retardation was in error.” His affidavit concluded by stating that “to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty . . . Mr. Hill meets the criteria for mild retardation. . . . Mr. Hill has significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning associated with significant deficits in adaptive functioning, with onset before age of 18.”

Soon thereafter the two other experts who in December 2000 had testified that Hill was not mentally retarded also repudiated their previous testimony. Each signed his own affidavit stating that he had reconsidered his previous testimony and that he now considered Hill to be mildly retarded. This meant that now all seven of the experts who had examined Hill were in agreement that Hill is retarded (and therefore ineligible for the death penalty).

Hill then filed his third state habeas petition in superior court, again raising the mental retardation claim that he was ineligible for execution. But this time there was fresh evidence bearing on the claim. Hill attached to the petition the newly discovered evidence in the form of the affidavits of the three experts. In the petition Hill asserted that his retardation claim was now proved beyond a reasonable doubt because all the experts agreed that he was retarded. The superior court, however, on the procedural ground that it had previously rejected the retardation claim, which was now res judicata, promptly dismissed the petition, and when Hill asked the Georgia Supreme Court to review that decision it promptly declined to do so.

In thus summarily rejecting Hill’s mental retardation claim, despite the new evidence, the Georgia courts acted unusually. Traditionally, the Georgia courts have been willing to consider the merits of a habeas petition raising a claim rejected in a previous habeas proceeding if there is newly discovered evidence bearing on the claim, which there certainly is in Hill’s case. If the Georgia courts had been willing to entertain the claim on the merits, Hill clearly would have prevailed. How could any court deny that Hill had proved retardation beyond a reasonable doubt when all the experts examining him agreed that he was retarded?

When Hill then turned to the federal courts for habeas relief he was again tossed out of court due to procedural niceties. Under the AEDPA, Hill could not file a second federal habeas petition without first obtaining permission to do so from the Eleventh Circuit. Hill sought such permission and presented the proposed second petition to the Eleventh Circuit. That petition raised the retardation issue again, pointed out that all the experts now agreed he was retarded, and had attached to it the affidavits of the experts who had changed their mind.

The Eleventh Circuit denied permission to file the habeas petition, for two technical reasons. First, although there was new evidence in support of it, the retardation claim was not new. Under the AEDPA, prisoners are prohibited from filing a second petition if it raises a claim presented in the original petition, and here, the Court said, Hill’s second petition, even though it was founded on newly discovered evidence, sought to raise a mental retardation claim rejected in his first federal habeas petition. Second, the Court said, even if the claim was new, under the AEDPA the second petition could be permitted only if there was newly discovered evidence of innocence, which was entirely lacking here. The dissenting judge, who voted to grant Hill the permission he had requested, rebuked her fellow judges, denouncing their notion “that a federal court must . . . condone . . . a state’s insistence on carrying out the execution of a mentally retarded person.” Under pre-1996 federal habeas corpus law, Hill would not have been required to obtain judicial approval before filing a second habeas petition, and very likely would have been granted relief on the merits of his retardation claim.

What’s Left of the Writ

Such, today, is the withered, tottering writ of habeas corpus. The writ has been so bled white that a death row inmate, whom all the experts agree is retarded and hence constitutionally ineligible for capital punishment, has been rebuffed by all the habeas courts he has petitioned for relief. The writ of habeas corpus is now such a shadow of itself that the courts are unable to grant a habeas petition from a death row inmate even though it is based on newly discovered evidence and clearly proves that executing the habeas petitioner would be unconstitutional.

Hill filed an original habeas corpus petition in the U.S. Supreme Court on May 22, 2013, and it is still pending. If, as is very likely, the Court denies it, Hill (barring an unforeseen miracle) will be unconstitutionally executed in a legal system with a writ of habeas corpus which has been so crippled that it can no longer fulfil its basic purpose.

The pending unconstitutional execution of Warren Hill raises doubts about the moral health of our society. Horribly, foolishly, dangerously, the Great Writ, once Brobdingnagian in majesty, is shrinking into Lilliputian absurdity. In violation of the Bill of Rights, officials of this state will strap Warren Hill down, insert needles into his body, and inject lethal chemicals into his bloodstream–and the writ of habeas corpus, which ought to prevent this from ever happening and which would in the past have prevented it, nowadays can’t and won’t. It is too withered, too weakened, too downgraded to perform its traditional noble office; instead of correcting unlawful confinement, habeas corpus now condones it.

The glory of the Great Writ is dimming in front of us, and we look on this with fatal apathy.

Chronology of the Case of Warren Lee Hill, Jr.

Apr. 7, 1988 The Georgia legislature enacts a statute which prohibits sentencing a mentally retarded person to death, but also requires a criminal defendant in a capital case who claims that he is retarded and therefore ineligible for the death penalty to prove the retardation beyond a reasonable doubt.

Aug. 17, 1990 Warren Lee Hill, Jr., a prison inmate serving a life sentence for murder at the Lee County Correctional Institution after shooting his 18-year old girlfriend eleven times with a 9 mm handgun, commits another murder, this time in prison. He brutally slays another inmate, Joseph Handspike, who is asleep in bed, by beating him in the upper body and face with a nail-studded board. During the attack several of Handspike’s teeth are knocked out and his left eye is detached from the socket.

July 29, 1991 Hill’s murder trial by jury begins in the superior court of Lee County.

July 31, 1991 The jury convicts Hill of murder.

Aug. 2, 1991 On the jury’s recommendation, Hill is sentenced to death.

Mar. 15, 1993 On the direct appeal filed by Hill, the Georgia Supreme Court affirms Hill’s murder conviction and death sentence. Hill v. State, 263 Ga. 37, 427 S.E. 2d 770 (1993).

Nov. 1, 1993 The U.S. Supreme Court declines Hill’s request that it review the Georgia Supreme Court’s decision. Hill v. Georgia, 510 U.S. 950 (1993).

April 14, 1994 Hill files a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the superior court of Butts county (location of the Jackson state prison, which contains Georgia’s death row). Among other things, the petition raises the claim that Hill is mentally retarded and hence not subject to capital punishment under the 1988 statute prohibiting execution of the retarded. The retardation claim had not been raised or decided at Hill’s trial or on the direct appeal.

Apr. 24, 1996 Congress enacts Title I of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), which drastically curtails the federal writ of habeas corpus for persons filing for relief on or after this date.

May 21, 1997 The superior court of Butts county issues a limited writ of habeas corpus. It finds that Hill has presented sufficient evidence of mental retardation and orders a jury trial of the issue. The State of Georgia appeals.

Feb. 23, 1998 On the state’s appeal, the Georgia Supreme Court reverses the superior court and sends the case back with directions that Hill be given an opportunity to prove mental retardation beyond a reasonable doubt, as required by the 1988 Georgia statute. The Court also directs that the mental retardation issue be decided by the superior court without the intervention of a jury. Turpin v. Hill, 269 Ga. 302, 498 S.E. 2d 52 (1998).

Nov. 2, 1998 The U.S. Supreme Court declines Hill’s request that it review the Georgia Supreme Court’s decision. Hill v. Turpin, 525 U.S. 969 (1998).

Dec. 2000 The superior court of Butts county conducts a three-day hearing on whether Hill is mentally retarded. Four mental health experts retained by Hill testify that Hill is retarded, while three experts for the State of Georgia testify that he is not retarded.

May 13, 2002 The superior court of Butts county enters an order determining that Hill has failed to prove retardation beyond a reasonable doubt. Under the 1988 Georgia statute, mental retardation has three components: (1) significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning (2) resulting in or associated with impairments in adaptive behavior which (3) manifested itself during the development period (i.e., before age 18). The Court finds that Hill has proved the first component beyond a reasonable doubt, but not the second.

June 20, 2002 The U.S. Supreme Court hands down its landmark decision in Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002), which holds that executing the mentally retarded violates the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishments. The clinical definition of mental retardation, the Court states, has three requirements: (1) significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning, as reflected by an IQ generally about 70 or below; (2) limitations on adaptive functioning; and (3) onset before age 18. However, the Court leaves it to the states to procedurally implement its holding.

Atkins alters the Georgia legal landscape. Executing a retarded person is now a violation not only of Georgia statutory law but also of the Bill of Rights.

Nov. 19, 2002 For the second time, the superior court of Butts county grants Hill’s habeas petition. It holds that the Georgia statute requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt to establish mental retardation is unconstitutional. The court also finds that Hill has proved by a preponderance of the evidence that he is mentally retarded but that he has not proved his retardation claim beyond a reasonable doubt. The State of Georgia appeals.

Oct. 6, 2003 On the state’s appeal, the Georgia Supreme Court by a 4-3 vote reverses the grant of relief. Requiring offenders to prove retardation beyond a reasonable doubt is not unconstitutional, the Court says. The Court accepts the superior court finding that Hill has failed to prove retardation beyond a reasonable doubt. Head v. Hill, 277 Ga. 255, 587 S.E. 2d 613 (2003). The three dissenters take the position that it is unconstitutional to require Hill to prove retardation by any standard other than proof by a preponderance of the evidence. They criticize the majority opinion under which, as the dissenters note, “the State may execute people who are in all probability mentally retarded. The State may execute people who are more than likely mentally retarded. The State may even execute people who are almost certainly mentally retarded. Only if a mentally retarded person succeeds in proving that retardation beyond a reasonable doubt will his or her execution be halted.”

Oct. 5, 2004 Hill files a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia. One of his claims is that he is ineligible for the death penalty because in the previous habeas proceedings in state court he proved his mental retardation by a preponderance of the evidence. Requiring him to prove retardation beyond a reasonable doubt violates the Eighth Amendment, Hill maintains.

Nov. 7, 2007 The district court dismisses Hill’s federal habeas petition. Hill appeals to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.

June 18, 2010 By a 2-1 vote, a three-judge panel of the Eleventh Circuit reverses and holds that Hill is entitled to federal habeas relief. Requiring a criminal defendant to prove his mental retardation beyond a reasonable doubt, as Georgia does, is a violation of the Eighth Amendment, the Court determines, and is contrary to the Atkins v. Virginia decision. The decision means that the State of Georgia will have to resentence Hill, this time to life imprisonment. Hill v. Schofield, 608 F.3d 1272 (11th Cir. 2010).

Nov. 9, 2010 A majority of the judges on the Eleventh Circuit vote to have the panel’s decision reheard en banc, i.e., by the whole Court, and so under the local rules of the Court the panel’s decision is automatically vacated. Hill v. Schofield, 625 F. 3d 1313 (11th Cir. 2010).

Nov. 22, 2011 By a vote of 7-4, the en banc Eleventh Circuit affirms the district court’s denial of habeas relief. The Eleventh Circuit rests its decision on a portion of the AEDPA which bars federal habeas relief to persons convicted in a state court (even though their federal constitutional rights were violated) unless the state court decision was not only erroneous but so grossly erroneous as to be contrary to, or involve an unreasonable application of, clearly established law as determined by the U.S. Supreme Court. Requiring offenders to prove retardation beyond a reasonable doubt does not violate Atkins or any other clearly established law as determined by the U.S. Supreme Court, the Eleventh Circuit concludes. Hill v. Humphrey, 662 F.3d 1335 (11th Cir. 2011).

June 4, 2012 The U.S. Supreme Court denies Hill’s request that it review the Eleventh Circuit’s en banc decision. Hill v. Humphrey, 132 S.Ct. 2727 (2012).

July 16, 2012 The Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles denies Hill’s clemency petition.

July 18, 2012 Hills files a second state habeas petition in the superior court of Butts county. It reasserts the mental retardation claim.

July 19, 2012 The superior court dismisses Hill’s second habeas petition on two grounds: (1) Hill had previously proved mental retardation by a preponderance of the evidence but not beyond a reasonable doubt, and (2) requiring Hill to prove retardation beyond a reasonable doubt is (as the Georgia Supreme Court held) constitutional.

July 20, 2012 Hill files a lawsuit in the superior court of Fulton county claiming that the lethal injection protocol of the Department of Corrections is invalid because it is a rule that should have been but was not adopted in accordance with the state’s administrative procedures act. Hill requests a stay of execution.

July 23, 2012 The superior court of Fulton county conducts a hearing on Hill’s lawsuit and then dismisses it and denies the stay.

Also on this day Hill requests the Georgia Supreme Court to allow him to appeal the dismissal, and to stay his execution. Later this same day the Georgia Supreme Court agrees to hear the appeal and stays the execution.

Also on this day the Georgia Supreme Court declines to review the superior court’s dismissal of Hill’s second state habeas petition, which he filed on July 18, 2012. The Court explains that the mental retardation claim, having been rejected in Hill’s previous state habeas proceeding, is res judicata.

July 27, 2012 Dr. Thomas H. Sachy, a psychiatrist who testified for the State of Georgia at the December 2000 hearing in Butts superior court, contacts Hill’s attorneys, telling them that he has reevaluated his previous testimony and that he now believes that his previous testimony that Hill is not mentally retarded was wrong.

Feb. 4, 2013 The Georgia Supreme Court affirms the decision of the Fulton county superior court dismissing Hill’s lawsuit attacking the validity of the state’s lethal injection protocol. The stay of execution entered by the Court on July 23, 2012 is dissolved. Hill v. Owens, 292 Ga. 380, 738 S.E. 2d 56 (2013).

Feb. 15, 2013 Hill files his third habeas petition in the superior court of Butts county. He again raises his mental retardation claim. This time, however, he relies upon newly discovered evidence proving that now all the experts who examined him say that he is retarded. In the habeas petition Hill explains that the three experts who at the 2000 hearing testified for the state that Hill was not mentally retarded have modified their views and now believe that Hill is retarded. Attached to the habeas petition is the 12-page affidavit of Dr. Sachy. In the affidavit Dr. Sachy explains at length why his previous testimony represented “erroneous judgment.” His previous testimony that Hill was not retarded was simply wrong, he announces. “I believe that my judgment that Mr. Hill did not meet the criteria for mild mental retardation was in error,” he says. He concludes by stating that Hill “meets the criteria for mild retardation.” Also attached to the habeas petition are affidavits by the two other experts for the state who in December 2000 testified that Hill was not mentally retarded. In their respective affidavits these experts announce that they have reconsidered their previous testimony and that they now consider Hill to be mildly retarded.

What we have here, therefore, is, in the words of Judge Rosemary Barkett, “the very unusual circumstance of medical professionals unequivocally reversing their prior diagnoses and concluding to a reasonable degree of medical certainty that Hill is retarded.”

Feb. 18, 2013 Hill’s third state habeas petition is dismissed by the superior court on procedural grounds.

Feb. 19, 2013 By a 5-2 vote, the Georgia Supreme Court declines to review the superior court’s dismissal of the third habeas petition.

Also on this day, the U.S. Supreme Court declines Hill’s request that it review the dismissal of his second Georgia state habeas petition, which he had filed on July 18, 2012. Hill v. Humphrey, 133 S.Ct. 1324 (2013).

Also on this day, and just three hours before his scheduled lethal injection, Hill files in the Eleventh Circuit a motion for leave to file a second federal habeas corpus. In an unreported decision, the Eleventh Circuit grants a temporary stay of execution to allow further briefing by both Hill and the state.

April 22, 2013 By a 2-1 vote, a panel of Eleventh Circuit judges dissolves the stay of execution and denies Hill permission to file a second federal habeas petition. In re Hill, 715 F.3d 284 (11th Cir. 2013). The majority rest their decision on the AEDPA. In the first place, the majority holds, Hill’s retardation claim was raised in his previous habeas petition, and yet the AEDPA provides that a second habeas petition “shall be dismissed” if it presents a claim that was presented in the previous habeas petition. In the second place, even assuming that Hill was raising a new claim, Hill still did not fall within the narrowly worded provision of the AEDPA that permits filing a second petition if it raises a new claim and there is newly discovered evidence of innocence, for Hill’s retardation claim does not mean he is innocent, only that a death sentence is inappropriate. The dissenting judge, Rosemary Barkett, stresses that “every expert who has ever evaluated Hill for mental retardation believes that he is mentally retarded,” and rejects the notion that statutory procedural rules can be allowed to prevent the courts from stopping an unconstitutional execution. Judge Barkett also argues that Hill’s second habeas petition need not necessarily be regarded as a successive petition under the AEDPA. The U.S. Supreme Court, she points out, has held that under some circumstances a second petition may be treated as a continuation of the first petition. The “perverse consequence” of the majority’s decision, Judge Barkett adds, “is that a federal court must acquiesce to, even condone, a state’s insistence on carrying out the execution of a mentally retarded person.”

May 22, 2013 Hill files a habeas petition originally and directly in the U.S. Supreme Court, asking that it overturn the Eleventh Circuit decision and grant him permission to file his second federal habeas petition. Under the AEDPA, this is the proper procedure available to Hill for obtaining review of the Eleventh Circuit’s refusal to permit him to file a second federal habeas petition. This habeas petition is still pending in the Supreme Court.

July 12, 2013 Hill files a complaint and a motion for equitable relief in the superior court of Fulton county. This lawsuit attacks the constitutional validity of Georgia’s new Lethal Injection Secrecy Act, which keeps confidential records or information identifying the businesses and individuals involved in manufacturing, supplying, compounding, or prescribing the drugs used to carry out lethal injection executions in Georgia.

July 15, 2013 Only hours before Hill’s scheduled execution, the Fulton county superior court stays the execution pending the filing of briefs in the lawsuit instituted by Hill three days ago.

July 18, 2013 The Fulton superior court conducts a hearing and hears testimony from witnesses in Hill’s lawsuit. At the end of the hearing the court continues the stay of execution and grants the State of Georgia permission to immediately file an appeal.

July 26, 2013 The state files its appeal with the Georgia Supreme Court.

Donald E. Wilkes, Jr. is a retired UGA law professor who taught for 40 years and has written more than 70 Flagpole articles.

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.